by Prof. Sarah Keene Meltzoff

Department of Marine Ecosystems and Society

Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science

University of Miami, USA

An original version of this case study grew out of the invitation from Prof. Paul Durrenberger to contribute a chapter to his book, State and Community in Fisheries Management: Power, Policy, and Practice (Durrenberger and King eds. 2000).

2000 Meltzoff, S. K., Nylon Nets and National Elites: Alata System of Marine Tenure Among the Lau of Fanalei Village, Port Adam Passage, Small Malaita, Solomon Islands". Invited Chapter in Durrenberger, E. Paul, and Thomas D. King, eds. 2000. State and Community in Fisheries Management: Power, Policy, and Practice. Westport, CT:Greenwood Publishing. 69-82.

Tiny jewels lie on the wet sand, jet black dotted in iridescent blues, yellow and orange stripes, green-red patterns. These miniature reef fish have been trapped by the small-meshed large nylon net now heaped in the front of the canoe. They mirror the thin catch carpeting the four-man dugouts which used to come home loaded. As the fishermen divide up the fish, girls swoop down to claim the juveniles. Digging holes by the canoe, they play at burial, marking graves with coconut fronds. Smaller kids toss the wiggling colors in the air. Some more children arrive with fishing poles, and recycle a few as bait. They’re headed for the tide pools along the fringing reef on the east shore of Fanalei’s island.

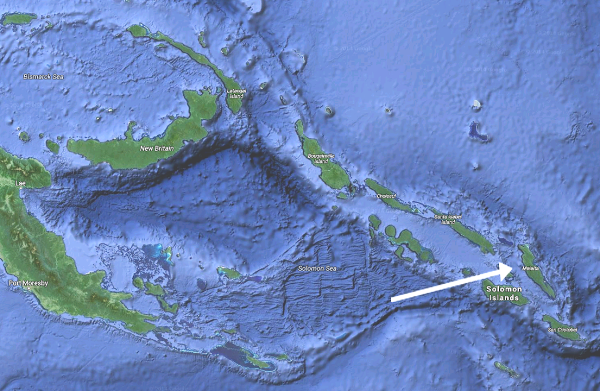

Until the introduction of modern nylon nets and access to an urban cash market, the alata system conserved the shallow reefs, and these juvenile fish, under the stewardship of the chiefly clan of Fanalei. Alata is the traditional or "custom" marine tenure system among the Lau “saltwater” people. This case explores how the fishing village of Fanalei on Port Adam Passage, Small Malaita, has altered their alata and customary use of reef resources. By setting the alata system into historical perspective, we understand the perpetual social, economic, political and environmental changes that interrelate and are constantly evolving Fanalei reef fisheries.

My multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork in the Solomons Islands started in Fanalei and Sa’a Villages of Small Malaita in 1973 (thanks to Thomas J Watson Fellowship), with the privilege of observing transformations in island life during the final years of colonial rule. This led to my dissertation fieldwork in cultural anthropology at Colombia University (thanks to ICLARM and the Rockefeller Foundation), followed by periodic fieldtrips through 1992. The ethnographic present for this case is 1988, when frantic alata net-fishing for cash was at its height.

"Civilization"—the Pidgin English term for the modern world of machines and manufactured goods, used in opposition to "custom"--came riding in on the coat-tails of British colonialization. The Solomon Islands were officially claimed by Britain in 1893. Civilization demanded Pax Britannica as part of the program of British direct rule to end the constant headhunting and raiding. “Civilization” also required that islanders enter into a world where cash is not only desirable but necessary. The British intentionally triggered the necessity for cash by imposing head taxes. The District Officer of Malaita would patrol and collect head taxes as well as illegal guns to tame this most dangerously wild place of British imagination where cannibalism was real.

When Independence arrived in 1978, at the end of the global colonial era, Britain seemed glad to divest. They had never developed extractive wealth or significant infrastructure for the Solomon Islands population now exploding. In 1972, on winding down colonial rule, the British made an effort to create a font of foreign exchange through a tuna fishing joint venture with Japan’s Taiyo Gyogyo—the world’s largest fishing company. (Meltzoff and LiPuma 1982) The skipjack pole-and-line fisheries of Solomon-Taiyo was supposed to become the major source of GNP for a budding nation-state dependent on foreign aid. But the story didn’t unfurl this way because Taiyo, a vertically organized company, declared joint venture losses for at least the first decade of operation, despite fine catches.

Solomon Taiyo, however, did become a popular alternative source of jobs in lieu of plantation labor. The “saltwater” youth of Fanalei immediately hired on as skilled fishermen. "Civilization” trumping “custom”, migrant labor instead of warfare had become the established social norm. Village desire for cash only escalated with Independence. Given such forces of change, the Lau's alata system and fishing within Port Adam Passage was primed for a drastic sea change.

--------------------------------------

(1) This paper is in honor of Wilson Ifunao. In 1973, he returned home from University of Papua New Guinea where he had studied Anthropology. I, too, having just finished college, arrived thanks to winning a Watson Fellowship to live anywhere in the world for a year. A Margaret Mead fantasy and a yearning for tropical seas landed me in the Solomons. Honiara was then a tiny palm-fringed British colonial capital set in American wartime architecture, roads, bridges, and linked to the outside world by WWII’s Henderson airfield. Honiara’s population was just 7,000 in a archipelago of about 200,000 people. And, Wilson was only one of just five Solomon Islanders with a university degree. He had just started working for government when he took me under his wing. He was warm and funny, deeply intelligent and thoughtful about the social change he was leading. We became friends and he invited me to go live in his traditional “saltwater” village, Fanalei, where his father was chief. A few years later, Wilson almost came to Stonybrook for his Ph.D. in anthropology. While a graduate student at Columbia, I was about to pick him up at the airport when he telegraphed that the Solomons government had just offered him too important post to turn down, the first in a distinguished career. Wilson and his wife from the Northern Lau, raised children who, in turn, are national elite. Many of Wilson’s siblings and cousins and their children are national elite. Wilson was an extraordinary member of an amazing chiefly clan, and a leader of its first generation of national elite. He died of heart trouble in 1996.

All photos by the author except for the overview map.