7 March 2012 - Open course "Can science save the seas?"

Introduction by Prof. Paul Jacobs

K1.105, Campus Solbosch

in the course of Prof. Jacobs with Cornelia E Nauen as lecturer; from 16 to 18h.

Prof. Paul Jacobs has an introductory course on the sciences for a mixed group of beginners in the natural and social sciences as a foundation course. He had invited a talk about the increasing challenges to the integrity of marine ecosystems and what this means to our societies, based on latest research results.

Despite pouring rain, a fair number of students had come to join the presentation and discussion.

The talk started with an introduction on the context of international cooperation to protect the seas interfacing science and society, arts and education and then went on to address the following sections:

- Why do we talk about a global fisheries crisis?

- Why does it matter?

- Seeking to explain human behaviour

- Some more ‘unconventional drivers’ of unsustainable fisheries

- What we can do together …

- So, can science save the seas?

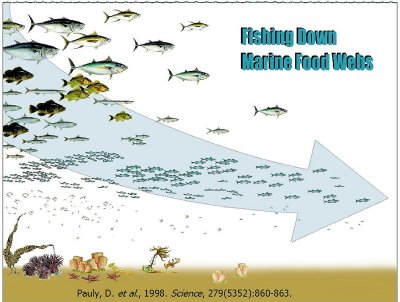

Emblematic for the global fisheries crisis is the dramatic decline of large predatory fish in the North Atlantic that took place over the last one hundred years and longer. This led to significant changes in the composition and functioning of marine ecosystems.

Unfortunately, these losses in the productivity and resilience of ecosystems is not confined to the North Atlantic, where fishing has developed strongly and has early on attracted scientific interest. Scientists from many different disciplines meeting for the International Symposium "Marine Fisheries, Ecosystems and Societies in West Africa - Half a Century of Change" in Dakar, Senegal, from 24 to 28 June 2002, just months before the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa, showed similar declines in even shorter periods in West Africa.

Unfortunately, these losses in the productivity and resilience of ecosystems is not confined to the North Atlantic, where fishing has developed strongly and has early on attracted scientific interest. Scientists from many different disciplines meeting for the International Symposium "Marine Fisheries, Ecosystems and Societies in West Africa - Half a Century of Change" in Dakar, Senegal, from 24 to 28 June 2002, just months before the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa, showed similar declines in even shorter periods in West Africa.

Why should we be concerned, even if we are not living directly on the coast or are eating fish on a regular basis? Well, we should, because at current trends the fisheries we know and the species we now like to have on our plates even occasionally may be gone by about 2050, within the lifetime of most of the students in the lecture hall. It happens throughout the oceans and is called "fishing down marine food webs".

Not only that, we are also seeing destruction of valuable habitat for many bottom living species through large-scale bottom trawling and other destructive production methods.

This in turn creates habitat for the polyps of jellyfish and other creatures, which are less desirable from a human consumption perspective, but also reflect structural changes in the way marine systems function after many other species have lost their living space.

Rampant overfishing is now the norm - too many boats chasing too few fish. Some economists have estimated that a large chunk of the world's fishing fleets are not only superfluous, but an active drain on their economies. Up to 50%, depending on the country, may only be 'viable' because of subsidies to their operation. In other words, they are loss-makers in times, when many people find it increasingly difficult to make ends meet.

Rampant overfishing is now the norm - too many boats chasing too few fish. Some economists have estimated that a large chunk of the world's fishing fleets are not only superfluous, but an active drain on their economies. Up to 50%, depending on the country, may only be 'viable' because of subsidies to their operation. In other words, they are loss-makers in times, when many people find it increasingly difficult to make ends meet.

Add marine litter, wide-spread illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing, bycatch, discards and other threats to that and you have an explosive mix, which should not leave anybody indifferent who would like to enjoy the beauty, food and ecosystem services of the sea also in the future.

What drives such folly? Conventional economics suggests that it's all about allocation of scarce resources and that it's better to have a little less now than wait a few years to get more. That's called the discount rate (a sort of negative interest). In uncertain times, one might operate with high discount rates and only accept to invest over longer periods in exchange for very high interest. That may be true for some investment strategies, but it has also been demonstrated that people do e.g. invest in their children and family, even if they don't get immediate or even guaranteed long-term financial and economic returns. When it comes to the regenerative capacity of nature, it does not take a biology PhD to understand that while it can be amazing, it can not match speculative Ponzi schemes (which, incidentally, also come crashing down with the next financial bubble).

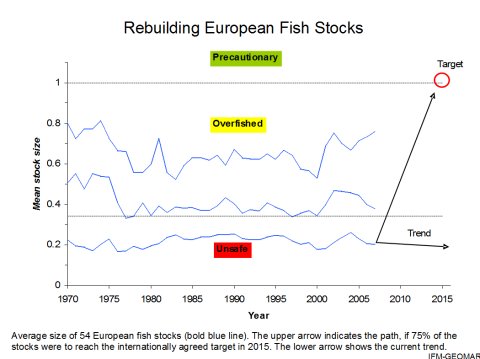

So, there is a point here of exercising a bit more precaution and resist the miraculous promises for cool headed study and assessment: it's even been done already: in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development Heads of State and Government solemnly decided to establish networks of marine protected areas by 2012 and to rebuild degraded marine ecosystems by 2015 so that they can produce maximum sustainable yield and be net contributors to the economy and to society at large.

So, there is a point here of exercising a bit more precaution and resist the miraculous promises for cool headed study and assessment: it's even been done already: in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development Heads of State and Government solemnly decided to establish networks of marine protected areas by 2012 and to rebuild degraded marine ecosystems by 2015 so that they can produce maximum sustainable yield and be net contributors to the economy and to society at large.

Well, you are forgiven to think that there is some urgency to act by now, because not much has happened since the decision was taken.

But not all is lost. Here are some action points - preferably in cooperation:

But not all is lost. Here are some action points - preferably in cooperation:

- Buy insurance against risk and uncertainty by creating marine protected areas;

- Value our great grand children’s fish as their fish, not ours;

- Integrate economics with ecology and other disciplines;

- Reduce sectoral approaches in preference to those that cut across all activities of society;

- Stop bad government subsidies to fisheries – Asia US $ 11.5 billion, Europe $ 5 billion, Latin America and Caribbean $ 4.5 billion;

- Help establish effective marine protected areas – the Convention on Biological Diversity foresees to protect part of the oceans - some progress - yet less than 1% are protected (probably 0.1% effectively);

- Promote sustainable forms of small-scale fisheries, recognise cultural diversity;

- Help enforce the law and stop impunity;

- Work on integrating sustainability principles, sciences and arts into curricula (university, lifelong learning, schools,...) and engage with opinion leaders;

- Meet our global peers and learn to collaborate

- Make scientific knowledge more widely available in the public domain;

- Encourage story telling and registration of memories to build bridges between different knowledge communities for mutual recognition and ability to cooperate on shared challenges.

Conclusion: science is important, even indispensable, for understanding, but ultimately, whether we change course and prefer protecting the sea from current widespread abuse is a societal decision, not a scientific one. The Powerpoint presentation is available here.