11-14th October 2010

by Prof. Stella Williams, Nigeria

I have known Dr. Linley Chiwona-Karltun for more than 20 years. We met by chance in 1985 when we were both participants of CTA’s sponsored visit to Malawi on a Fisheries/Aquaculture Country Visit. CTA is, of course the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (ACP-EU Cotonou Agreement), based in Ede, The Netherlands. Since then we have kept in touch and so, when she invited me to make a week-long visit to her master's class at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) in Uppsala in October 2010, I accepted.

My visit was an official one to teach, mentor and serve as a link to her international students, who are registered for a Master’s degree in Rural Development. She wanted her students to have an opportunity to learn from an International Scientist with a passion for fisheries and aquaculture and working very closely with young people.

The snapshots capture some moments in class. The first photo is one that shows Linley introducing me to the class at the open seminar and you will see some of the Mundus maris poster on the board. Linley is standing in front of the class while I am seated behind a desk waiting to give my seminar. The other photo shows me responding to questions from the students. Situation photos by Chad Ellingson, Uppsala.

Dr. Linley Chiwona-Karltun is a native of Malawi but now a Swedish citizen. She earned a PhD in International Health and currently has a Master’s Class of 32 students from around the Globe: Sweden, United States of America, Africa (Ghana, Kenyan, Somali etc.) United Arab Republic, India, Bangladesh and Latin America to name but some of the countries where the students came from.

I spent three days with Linley in her classes. As I am wearing different hats, I could bring a wide range of perspectives to the students – in my role as Chair of the African Women in Agricultural Research & Development (AWARD) and my activities in Mundus maris, I could enrich the technical arguments with a broader cultural and people-centered perspective, which struck a cord with the students. So I answered questions from students on their major areas of interest to the best of my ability and this gave both Linley and me the chance as well to introduce Mundus maris to the Students in addition to my participation in their courses and the Open Seminar given on the 14th of October.

I spent three days with Linley in her classes. As I am wearing different hats, I could bring a wide range of perspectives to the students – in my role as Chair of the African Women in Agricultural Research & Development (AWARD) and my activities in Mundus maris, I could enrich the technical arguments with a broader cultural and people-centered perspective, which struck a cord with the students. So I answered questions from students on their major areas of interest to the best of my ability and this gave both Linley and me the chance as well to introduce Mundus maris to the Students in addition to my participation in their courses and the Open Seminar given on the 14th of October.

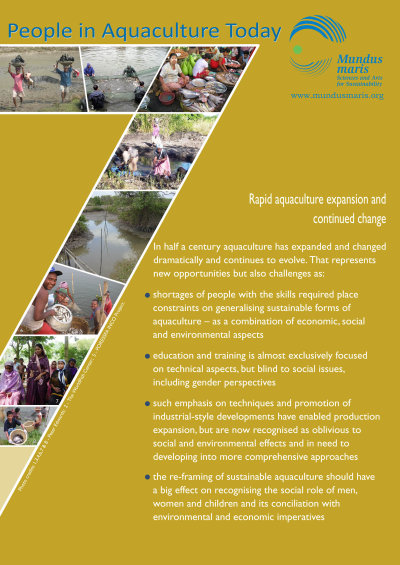

The Mundus maris aquaculture posters below were shown in this context together with others illustrating recent advances in fisheries sciences and how to connect the science results to a wider public of interested people. It is no accident that they focus on people not only on the relevant technicalities. The challenge is indeed to direct the best of science at societal issues and engage critically with all groups of people to enhance their ability for analysing the opportunities and threats - hopefully enabling more informed decision-making.

Among the many questions asked by the students were, for example: why did the fisheries crises take hold globally in comparison to what we see in land animal science and husbandry or forestry?

Among the many questions asked by the students were, for example: why did the fisheries crises take hold globally in comparison to what we see in land animal science and husbandry or forestry?

Well, unfortunately the fisheries crisis is not so very different from what we see in wild land animals and in forestry. Overharvesting is rampant, including of bush meat, and populations go down, except when there are effectively-protected areas where habitat is maintained and hunting or clear-felling are prohibited. Such protection tends to work best, when neighbouring human populations can earn a living (as guards, guides, etc.) through being part of the protection scheme, not being excluded entirely themselves.

The IUCN Redlists of endangered species are growing all the time. We are witnessing unprecedented loss of biodiversity on Earth, at a rate 1000 times higher than background extinction rates over long historical periods. This is now considered a threat as serious as climate change.

In the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in Nagoya, Japan, will work towards progress and particularly on an agreement for benefit sharing from genetic resources between developing and industrialised countries to build the mutual trust necessary to protect biodiversity more effectively. There are a number of useful resources available on this website to dig further into the fisheries crisis and what can be done about it.

Another question was: How quickly will aquaculture serve as a supply substitute for meeting demand unmet by capture fisheries?

With stagnant or declining capture fisheries production since the late eighties/early nineties and huge efforts pouring into aquaculture, both freshwater and marine, more than 40% of global supplies of fisheries products for human consumption already stem from aquaculture, most of it in Asia. If wild resources would be better managed their productivity could be greatly enhanced. But this is a big if, as recent decisions e.g. at the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) showed – catch quotas were not reduced sufficiently to accommodate the pressures of the industry of some member states, reducing the chances that this emblematic species will recover from its lowest historical abundance.

With stagnant or declining capture fisheries production since the late eighties/early nineties and huge efforts pouring into aquaculture, both freshwater and marine, more than 40% of global supplies of fisheries products for human consumption already stem from aquaculture, most of it in Asia. If wild resources would be better managed their productivity could be greatly enhanced. But this is a big if, as recent decisions e.g. at the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) showed – catch quotas were not reduced sufficiently to accommodate the pressures of the industry of some member states, reducing the chances that this emblematic species will recover from its lowest historical abundance.

There was curiosity about tilapia aquaculture in Africa: why is it that only tilapia is being produced and not other species of fishes?

Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, originates in Africa, but has become a mass produced product in aquaculture also in other parts of the world, because of its sturdiness and ease of reproduction and maintenance. As a plant and detritus eater, it is low in the food web and does not necessarily require expensive pelleted feed. Normally aquaculture develops to respond to demand in urban centres of consumption, where clients have purchasing power, when wild-caught fish is not available in sufficient quantity and of the right quality. When demand in many places in Sub-Saharan Africa can be met by cheap fresh, frozen or cured fish from marine and inland capture fisheries, the demand for (more expensive) aquaculture products may not be high enough to form a solid economic basis for starting up aquaculture. This is evolving, not the least as a result of overfishing of wild resources and urbanisation processes, which create stronger market demand. Unlike in e.g. inland China, the abundance of cheap wild caught fish did not create pressure for developing aquaculture in Sub-Saharan Africa for a long time. If demand for fish outstrips supply, aquaculture skills may well be acquired on a larger scale than is currently the case. The three aquaculture posters invite reflections about how to make sure a sustainable relation is found between production objectives, people and the environment in this dynamically developing sector world-wide.

Another student insisted: why can Africa not produce high-priced fish species selling in Western markets?

Another student insisted: why can Africa not produce high-priced fish species selling in Western markets?

Conditions are not uniform 'in Africa'. Egypt, Tunisia and other North African countries produce e.g. seabass and other species for the European or tourist markets. Shrimp are also being cultured in Madagascar and some other countries. These highly priced species have in common that they need animal protein (often in the form of fish meal and oil) as they are predators or carrion feeders high in the food web. While advances have been made to replace fish meal by soya and other plant materials to allow this sort of aquaculture to keep developing, these rather sophisticated forms of aquaculture have not taken root in Sub-Saharan Africa. Contributing factors are low priority for associated research and training of technical and managerial staff, cost structures, among others. One might also argue that in the face of wide-spread food insecurity focus quantity and availability of low cost fish food might be of higher priority. Moreover, there may be other areas than carnivore aquaculture, where value-added export products can make use of natural resources and people's existing skills to generate economic benefits from trade.

There were more questions than can be reported here, but one also needs mention: How can young students like us at SLU be of service to Africa?

SLU’s Department of Urban and Rural Development has an excellent curriculum. The students therefore have a good base and foundation to assist them prepare for the often complicated situations they will be confronted with in the future jobs. They might also join civil society and other groups involved in development projects, including initiatives like Mundus maris. Additionally, Dr. Chiwona-Karltun’s method of increasing the educational background of her students by inviting international experts to give seminars is a fantastic way of enabling her Masters’ students to expand their linkages and network for future activities. I am very impressed with SLU’s efforts to expand the reach of their educational support, thereby engaging experts from around Europe and globally in supporting and mentioring their students. My visit and those of other international experts on urban and rural development is a useful strategy for encouraging the students to link with groups active around the globe.

Since my visit, some of the students have sent me e-mails and we have continued to exchange. A number of then informed me that they visited our website and were impressed with the activities and contributions visible so far. I hope that some of them take in on the spirit of promoting sustainable livelihoods in the holistic and people-centred ways and may even decide to join our group.

For further interaction with the young people at SLU and their professors, contact Linley:

Linley Chiwona-Karltun, PhD International Health

Department of Urban & Rural Development

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

Box 7012, SE-750 07, Uppsala, Sweden

Diese E-Mail-Adresse ist vor Spambots geschützt! Zur Anzeige muss JavaScript eingeschaltet sein!