Exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK.

Exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK.

This exhibition was curated jointly by the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, UK and the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, US. It was on display at the Yale Center for British Art from 12 February to 3 May 2009 and at the Fitzwilliam Museum from 16 June to 4 October 2009. The catalogue accompanying the exhibition is edited by Diana Donald and Jane Munro and published in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

The exhibition explored the effect of Darwin's science and theories on the visual arts in the 19th century on both sides of the Atlantic (with emphasis on the US and Europe). In those days of lesser specialisation in the sciences and other spheres of life, as the exhibition guide rightly highlights, "[t]he interchange between science and art was a two-way street". Key science works, such as Darwin's 'On the origin of species by means of natural selection' (1959) and 'The descent of man' (1971), were read, publicised by the media and debated by a broad public. These works did not fail to trigger reactions from artists as well.

The exhibition catalogue is structured in four major sections with a total of 12 chapters: (a) Darwin at home: Observation and taste at Down House; (b) Darwinian theory and the picturing of the natural world; (c) The descent of humankind: Animal ancestry, cultural evolution and racial theory; and (d) Darwin, aesthetic theory and nineteenth-Century art movements.

The exhibition touched comparatively little on marine and coastal topics and was richer in materials of how the notion of the 'survival of the fittest' had inspired art work on such representations as agreesion by predators on game. Its extension to 'social Darwinism' was reflected in paintings depicting destituted workers and people in poor houses supposedly as less fit. Indeed, Darwin himself with his stand against slavery and his openness of mind towards people of cultures and social status other than his own had been aware of the potential contradiction between the principle of natural selection of the fittest on random variation and cooperation among humans. The apparent puzzle has been explored ever since in social science research exploring Darwinian principles as an explanatory pattern. The argument is being settled in recent publications in favour of evidence for a selective advantage for cooperation rather than competition or non-cooperation, even when cooperation extends beyond direct kin.

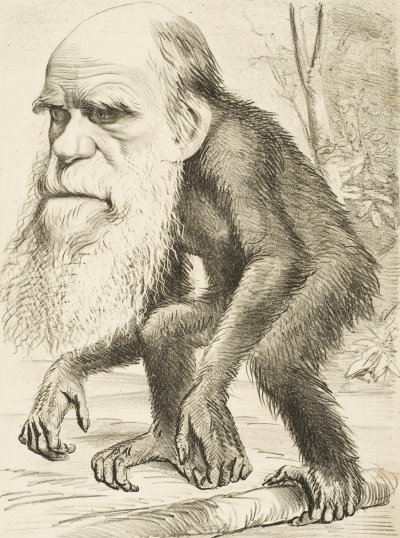

The section dedicated to 'The descent of man' showed varied series of photos and lithographs of people of different ethnic and cultural background. The catalogue discusses some of the derivations feeding racism. Clearly the book captured the imagination of the public - even to this day - and some of the pieces on display show how far the scientific debate engaged the wider public.

The section dedicated to 'The descent of man' showed varied series of photos and lithographs of people of different ethnic and cultural background. The catalogue discusses some of the derivations feeding racism. Clearly the book captured the imagination of the public - even to this day - and some of the pieces on display show how far the scientific debate engaged the wider public.

Among the cartoons of the day reflecting on the implications of Darwin's book is "A venerable orang-outan" depicting an ape with Darwin's head that appeared in The Hornet, 22 March 1871. A variation on the theme, this time showing Darwin in his characteristic elevated position on a book in an armchair and with one ape hand and leg appeared in Vanity Fair, 30 September 1871, under the title 'Men of the day'. It was also on display in poster size in the exhibition.

Modern day humour inspired by Darwin or by what passes as evolution gets still expressed also through cartoons. A collection of caricatures, cartoons and reflections on how visual information influences and propagates understanding of science and other resources is available here (Blog of Michael D. Barton).

The extent to which the science engaged the public, and was discussed in all kinds of general media of the days of Darwin was remarkable. It was not only the subject of conversation among a few specialists. Darwin's findings influenced areas of enquiry and the arts well beyond the natural history and adjacent fields. The exhibition was a contribution towards engaging again a wider public in the science and its many ramifications.

The extent to which science (and technology) affect every aspect of our lives and our environment today more than justify these efforts. One would certainly wish that all humankind nowadays had access to up-to-date science and its results to navigate in the turbulent waters of bringing human civilisations back into balance with their natural environments and with one another.