Microplastics are increasingly recognised as a growing public health issue. The research reported here was carried out within the framework of an academic collaboration supported by Mundus maris with the University of Belgrano, Argentina. It aims to document the environmental problems represented by microplastics in aquatic ecosystems, with a particular focus on the Buenos Aires coast of the Río de la Plata. The samples were taken at the Buenos Aires Fishermen's Club.

Microplastics are increasingly recognised as a growing public health issue. The research reported here was carried out within the framework of an academic collaboration supported by Mundus maris with the University of Belgrano, Argentina. It aims to document the environmental problems represented by microplastics in aquatic ecosystems, with a particular focus on the Buenos Aires coast of the Río de la Plata. The samples were taken at the Buenos Aires Fishermen's Club.

Microplastics, defined as plastic fragments smaller than 5mm, include a variety of particles such as microfibers released from clothing during wash cycles, fragments of degraded plastic products, and microbeads from cosmetic products. This study underscores the importance of understanding how these pollutants impact marine life, particularly fish that make up a crucial link in the aquatic food web.

The research casts some light on the environmental problems that may arise from the increasing presence of such microplastics in the water, sediments and aquatic life.

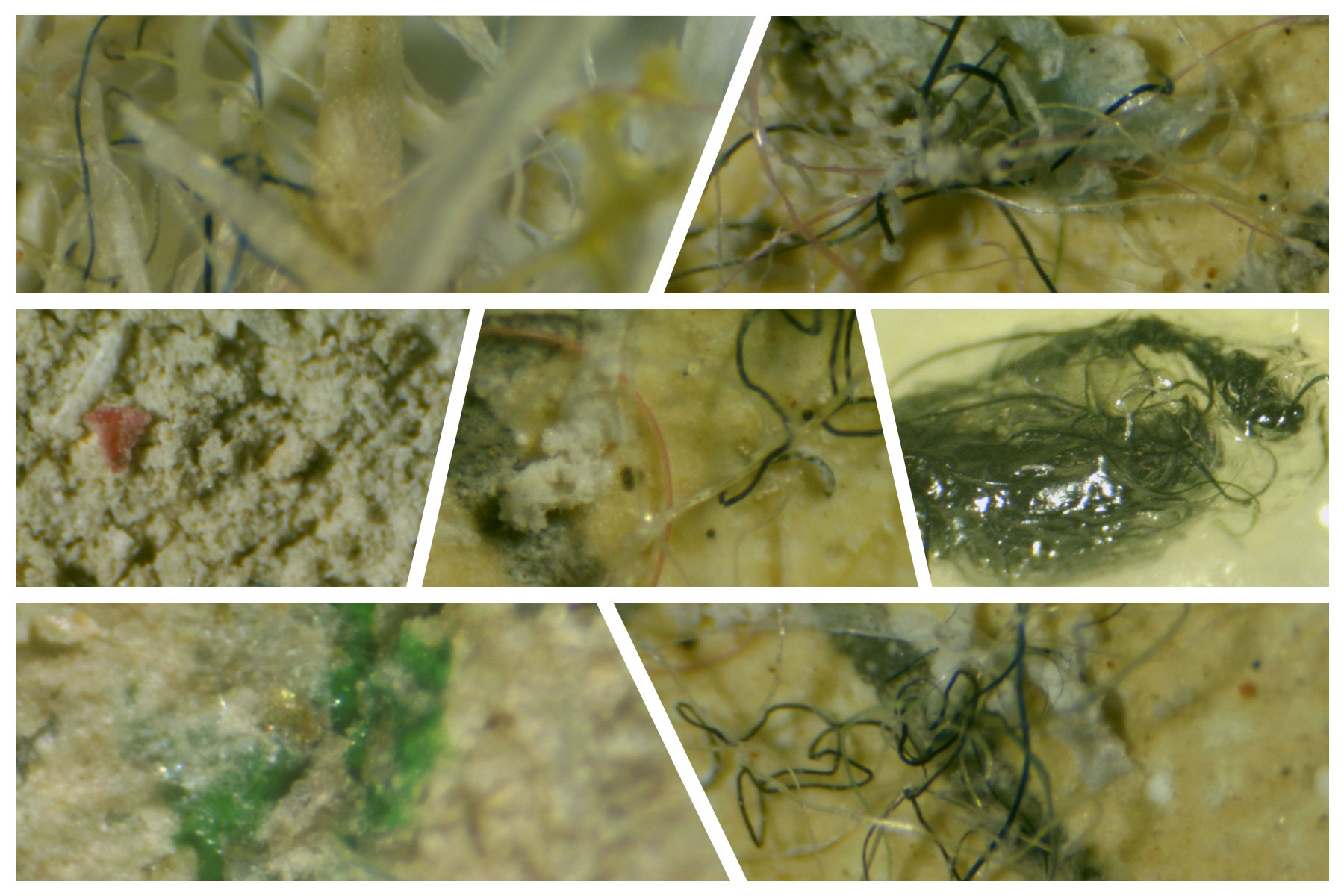

Lic. Carla Bonelli, a researcher on the team led by Dr. Marcelo Morales Yokobori, focused on analyzing the presence of microplastics in two species of fish in the Río de la Plata: Parapimelodus valenciennis, commonly known as "yellow catfish" of a bit more than 24 cm maximum length, and Megaleporinus obtusidens, or "boga" which reaches a much bigger size of above 70 cm. These species were chosen because of their distinct feeding habits. The yellow catfish is a bottom feeder, while the boga can feed both at the bottom and in the water column. This could influence their exposure and chance of accumulation of microplastics. The results revealed that microfibers make up the majority of microplastics found in these fish, highlighting the role of human discharges into the envronment, such as through laundry that, if not going through sewage treatment, is contributing to polluting aquatic habitats.

A notable finding of the study was the predominance of blue and light microfibers, with a low proportion of blue ones in guts. This contrasts with previous findings from colleagues in the near coasts. This could be attributed to the fading of fabrics during digestion or in the environment.

In addition, the study found no statistically significant differences in the relative amounts of different types of microfibers between the two species examined, indicating a homogeneous distribution of these pollutants in their environment and, therefore, in their food sources. No obvious bioaccumulation through the aquatic food web was observed as bigger individuals of boga had clearly lesser amount of microplastics. This result corroborated by similar findings elsewhere suggests the extent of the problem of microplastic pollution and the need to address this issue at a global level. Even if no higher concentrations were found in bigger 'boga', considering that this an appreciated food fish for humans, by extension, they will be exposed to microplastics in their diet. It should also be noted that microplastics can act as vectors of other pollutants due to the physicochemical properties of their surfaces, which increase as more fragmentation occurs.

In addition, the study found no statistically significant differences in the relative amounts of different types of microfibers between the two species examined, indicating a homogeneous distribution of these pollutants in their environment and, therefore, in their food sources. No obvious bioaccumulation through the aquatic food web was observed as bigger individuals of boga had clearly lesser amount of microplastics. This result corroborated by similar findings elsewhere suggests the extent of the problem of microplastic pollution and the need to address this issue at a global level. Even if no higher concentrations were found in bigger 'boga', considering that this an appreciated food fish for humans, by extension, they will be exposed to microplastics in their diet. It should also be noted that microplastics can act as vectors of other pollutants due to the physicochemical properties of their surfaces, which increase as more fragmentation occurs.

The research highlights the urgency of implementing measures to reduce the release of microplastics into the environment, as well as to improve wastewater treatment processes and promote sustainable consumption and production practices. In addition, it suggests the need to continue exploring the long-term effects of microplastic pollution on aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, as well as to develop more effective methodologies for monitoring and removing them from the environment. Microplastic pollution in the Río de la Plata not only represents a local environmental challenge, but also reflects a global environmental problem that requires coordinated and sustained actions to mitigate.

The current negotiations for a legally binding treaty to comprehensively address the full life cycle of plastic, including its production, design, and disposal and all associated forms of pollution by the end of 2024 are a most welcome perspective. We still have to deal with the enormous quantities already in freshwaters and seas, however.

The next steps should be to better understand the dispersion dynamics of these microplastics, as well as their formation and origin, associated with meteorological fluctuations. It will also be important to determine with spectroscopic analysis which types of plastics predominate, thus facilitating traceability to detect their sources and target preventive action.

Specific toxicity tests were not carried out in this context, but evidence is gradually building up through this growing research field. The exploration of complex reactions in the bodies of various organisms is a relatively novel area of investigation not yet leading to ascertained cause-effect relations.