Excellent opportunity to join a lecture of acclaimed author and long-time friend, Daniel Pauly, at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, Netherlands, on 2 September 2023. Despite the weekend, the lecture hall was packed full with scientists, managers, representatives of civil society and nature protection organisations, media and some people from government departments. They were not disappointed in their expectation to hear a bold interpretation of deep history of our species as it invaded every last corner of the planet. Means, as a species we are successful, aren't we? Let's see in a whistle stop tour through our history.

Excellent opportunity to join a lecture of acclaimed author and long-time friend, Daniel Pauly, at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, Netherlands, on 2 September 2023. Despite the weekend, the lecture hall was packed full with scientists, managers, representatives of civil society and nature protection organisations, media and some people from government departments. They were not disappointed in their expectation to hear a bold interpretation of deep history of our species as it invaded every last corner of the planet. Means, as a species we are successful, aren't we? Let's see in a whistle stop tour through our history.

Our species separated from chimps some six million years ago, but only in the last 2 to 300,000 years has the development of language allowed to form larger groups cooperating increasingly effectively in their survival tasks. Speech allows symbolic thinking. As occupation of ecological space is generally regulated by predator-prey relationships, our species evolved from being prey of large predators to becoming a formidable predator itself.

Signs of symbolic thinking marking group identity have been found in what is now South Africa in abalone shells with rests of ochre pigments used to as body paint, use of harpoons and other gear. We do not yet know whether these are the very earliest human artefacts, because possibly older bones have been recently found in North Africa. But what archeologists and geneticists could reconstruct is that modern Homo sapiens moved out of Africa in the late pleistocene, approximately 70,000 years ago, probably around Yemen when the sea level was much lower than today during a period when the Arabian peninsula was green.

Signs of symbolic thinking marking group identity have been found in what is now South Africa in abalone shells with rests of ochre pigments used to as body paint, use of harpoons and other gear. We do not yet know whether these are the very earliest human artefacts, because possibly older bones have been recently found in North Africa. But what archeologists and geneticists could reconstruct is that modern Homo sapiens moved out of Africa in the late pleistocene, approximately 70,000 years ago, probably around Yemen when the sea level was much lower than today during a period when the Arabian peninsula was green.

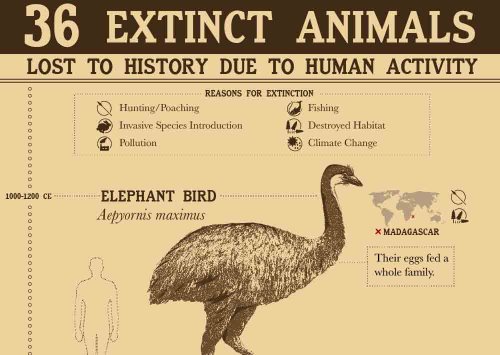

Within about 10,000 years H. sapiens reached Australia to the east and within 10 to 20,000 years populated Europe to the West. On its path, it wiped out all large animals within a rather short period of time. Gary Haynes writes in the 'Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene' first edition in 2018, in his chapter titled 'The evidence for human agency in the Late Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions' published by Elsevier:

"The timing of the arrival of humans on each continent parallels the disappearance of many megafaunal genera. The Late Pleistocene also saw climate-caused changes in plant communities and moisture regimes, which would have affected megafaunal genera in most regions; yet, the animals had survived numerous earlier changes and recovered each time. Only the presence of modern humans clearly sets the late Pleistocene changes apart from the earlier climatic fluctuations."

In New Zealand, for example, within a period of less than 200 years after the arrival in the 13th century of Polynesians on the island, the nine flightless moa species were extinct.

|

|

|

| Facsimile of key source book | Erosion - Image by Brigitte Werner from Pixabay |

But what was it making H. sapiens relentlessly move? Daniel Pauly citing David R. Montgomery submitted that it were consecutive food production crises from exhaustion of their agricultural lands that drove human groups to have to move and find new lands and food sources. This was the case with all the major cereal crops sustaining large populations: millet in West Africa, rice in China, wheat in the Middle East. Various mechanisms have been cited, such as water logging and salinisation rendering lands infertile and unable to produce the required quantities of food needed to sustain the civilisations in question. Erosion from wind and water, the relentless geological processes which grind entire mountains to grains over long periods continues to be a factor today in desertification and loosing agricultural land that is not well tended.

Loss of agricultural productivity and fights over food sources explains many conflicts, including the civil war in the US (1861-65), which was less about the abolition of slavery and primarily driven by the attempt to extend the plantation economy northwards as soils in the south lost fertility.

The last big expansion before European colonialism was into northern Atlantic waters to catch more fish and sealife. As the Catholic church restricted meat consumption for long periods of the year, fish and many organisms like turtles and other marine life declared as fish were much in demand. The Hanseatic League, a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe set up in the 1200s first became prominent by controlling the salted herring (Clupea harengus) trade in the Baltic. As of the 1300s dried cod (Gadus morhua) from northern Norway through their outposts in Bergen. In the 14th century trawling with sail boats was invented in England, a development that helped to expand the economic base of the economy.

As of the 15th century the cod fishery with dories off what is now Canada produced around 100,000 tons of cod per year. At that level, the fishery lasted almost five centuries, but the massive deployment of industrial trawling with fossil fuel driven steel ships especially after WWII finished off the formerly immensely rich cod populations. And, as we know, they have not recovered after the collapse in early 1990s.

As of the 15th century the cod fishery with dories off what is now Canada produced around 100,000 tons of cod per year. At that level, the fishery lasted almost five centuries, but the massive deployment of industrial trawling with fossil fuel driven steel ships especially after WWII finished off the formerly immensely rich cod populations. And, as we know, they have not recovered after the collapse in early 1990s.

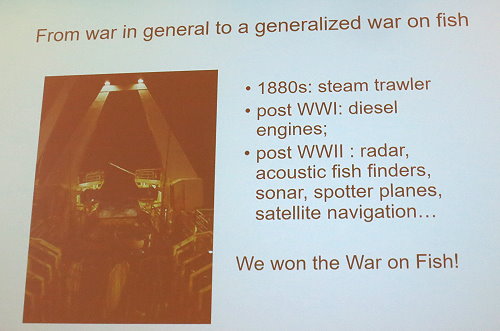

The industrial revolution introduced fossil energy from plant growth compressed over millions of years to produce steel and other materials in large quantities. In the last decades of the 19th century that supported fleets of warships so that Britannia ruled the oceans. After the first and second World Wars, steel vessels were massively deployed in the fishery together with all the military technology originally developed for spotting planes, sonar against submarines, later satellite navidation and more.

All this was thrown at the fish, landed in rapidly increasing quantities. Today, the biomass of fish around the UK is only 5% of what it used to be before the war.

And Pauly continues, "We literally moved from war in general to generalised war on fish. And guess what, we won the War on Fish!".

In the second half of the last century, already in the 1970s and 1980s to compensate for resource depletion around Europe and in the North Atlantic, the fisheries pushed further south and started fishing deeper down. The exploratory ground trawl fishing trips of German research vessels pulled up huge amounts of bottom dwelling animals as so-called bycatch together with the targeted cod and other fish. All the undesired bycatch went overboard to avoid filling the cooling space with lower prized or unedible species. That was a common practice on industrial vessels.

What meant 'further south'? It meant development aid for example for Indonesia - and other tropical countries - in 1970s to develop trawl fisheries. It so happened that Pauly was working as a young professional on one of the exploratory research cruises in the Java Sea in Indonesia in formerly untrawled waters in 1975-76. He was then one of few people witnessing and documenting in a few photos how the bottom trawls were bringing up huge sponges and a large array of bottom dwelling species, but comparatively few fish. Most of the catch in these pristine water was thus thrown away as useless. Few of the shrimp, and even fewer flatfish loved in Dutch cuisine but rare in the tropics, and few of the dozens if not hundreds of fish species present in small quantities were even known. This tremendous destruction of habitats essential for a functioning ecosystem went on largely unknown and unnoticed by the public.

What meant 'further south'? It meant development aid for example for Indonesia - and other tropical countries - in 1970s to develop trawl fisheries. It so happened that Pauly was working as a young professional on one of the exploratory research cruises in the Java Sea in Indonesia in formerly untrawled waters in 1975-76. He was then one of few people witnessing and documenting in a few photos how the bottom trawls were bringing up huge sponges and a large array of bottom dwelling species, but comparatively few fish. Most of the catch in these pristine water was thus thrown away as useless. Few of the shrimp, and even fewer flatfish loved in Dutch cuisine but rare in the tropics, and few of the dozens if not hundreds of fish species present in small quantities were even known. This tremendous destruction of habitats essential for a functioning ecosystem went on largely unknown and unnoticed by the public.

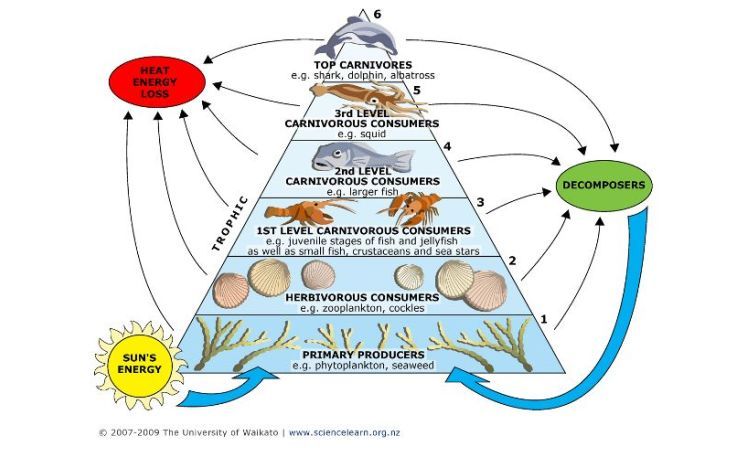

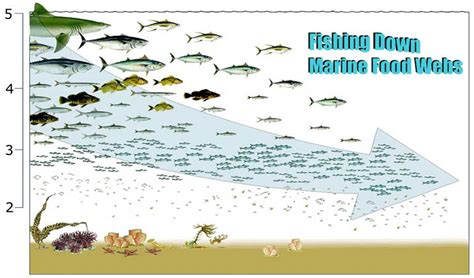

How does such an ecosystem function? Biologists speak of a trophic pyramid. At the base in the marine environment are mostly small plankton algae, primary producers which transform sunlight and nutrients in the water through photosynthesis into organic matter. These are consumed at the next level by copepods and other crustaceans, but also fish larvae and other small zooplankton. These are the first level of consumers, which in turn are eaten by herrig, sprat and other small pelagic fish. These are prey to bigger fish and so on. The energy transfer from one trophic level to the next is roughly only 10%, 90% is needed for staying alive and growing.

As industrial fisheries have caught copious quantities of big fish and mammals, and marine birds high in the trophic level of the food web they have increasingly also caught the prey of these animals. That not only starves the remaining predators as can be seen in collapsing bird populations, but impoverishes the entire marine food web leading to high vulnerability and malfunction in their ecosystems.

As industrial fisheries have caught copious quantities of big fish and mammals, and marine birds high in the trophic level of the food web they have increasingly also caught the prey of these animals. That not only starves the remaining predators as can be seen in collapsing bird populations, but impoverishes the entire marine food web leading to high vulnerability and malfunction in their ecosystems.

Currently approximately 20% of global catches are by trawling with all the destructive side effects for habitats turned into rubble and high CO2 emissions which have recently come into stronger focus as the climate crises broadens its grip.

As a parenthesis to unfolding this global picture, Daniel Pauly also mentioned how, thanks to an international collaboration of hundreds of researchers from around the globe he leads in the framework of the Sea Around Us Initiative, named after Rachel Carson's homonymous book, they have reconstructed national catches of all countries since 1950.

This huge effort is essential to complement and correct incomplete data governments report to FAO for compiling global statistics. But these often do not report catches by small-scale fishers, recreational fishers, and do not even attempt to estimate subsistence production.

This huge effort is essential to complement and correct incomplete data governments report to FAO for compiling global statistics. But these often do not report catches by small-scale fishers, recreational fishers, and do not even attempt to estimate subsistence production.

Likewise they do not estimate discards at sea (they report 'nominal landings') and make no attempt to estimate illegal catches.

For a more realistic appreciation e.g. for management or investments these more complete datasets are indispensible.

So, where does all this leave us as we take in the extent of human impact on every last corner of the planet? We know what needs to be done, even if implementing these measures is difficult:

stop harmful subsidies which fuel continued industrial overfishing, which would otherwise largely stop as unviable

stop harmful subsidies which fuel continued industrial overfishing, which would otherwise largely stop as unviable- set low quotas for fishing to allow resources to rebuild and ecosystems to recover normal functioning which would also help coping better with climate change

- establish large marine protected areas that are really protected, not only paper parks.

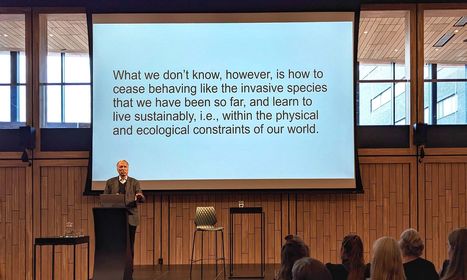

The big challenge is, can we stop behaving as a highly efficient and effective invasive species?

That closing question in turn triggered a short but lively Q&A session which reinforced the challenge to face these inconvenient truths and think of how to put the lessons into action.

Text by Cornelia E. Nauen; the recording is accessible here (in English).