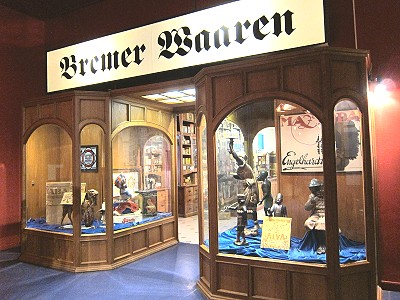

The Hanseatic City of Bremen has a long tradition in the sciences and arts and an even longer one in international commerce. Its rich history, diverse people, civic liberties and interesting architectural heritage are attractive for locals and visitors alike. Countless stories reflect the city's connections with the sea and far-flung places around the globe. The Overseas Museum holds vast and diverse collections of artefacts about its own history and how it is connected to other parts of the globe.

The Hanseatic City of Bremen has a long tradition in the sciences and arts and an even longer one in international commerce. Its rich history, diverse people, civic liberties and interesting architectural heritage are attractive for locals and visitors alike. Countless stories reflect the city's connections with the sea and far-flung places around the globe. The Overseas Museum holds vast and diverse collections of artefacts about its own history and how it is connected to other parts of the globe.

The research credentials of its state university are growing and the Leibniz-Centre for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT) on campus has accumulated more than 20 years experience of international science cooperation with teams in countries as diverse as Namibia in Southern Africa, Peru in Latin America, Solomon Islands in Oceania and Indonesia in Asia.

ZMT has long invested in scientific capacity building of young marine scientists in Germany as well as in partner countries and institutions by devising and conducting joint research. The two-way staff exchange, summer schools and joint publications are crucial, not only for ensuring scientific excellence across disciplinary boundaries, but also for mutual learning about the respective societal contexts in which research is being done.

It goes therefore without saying that pushing the knowledge frontiers on complex marine ecosystems in the tropics in such a collaborative mode is intertwined with learning also about the respective local cultures of the partners.

It goes therefore without saying that pushing the knowledge frontiers on complex marine ecosystems in the tropics in such a collaborative mode is intertwined with learning also about the respective local cultures of the partners.

Its particular international and thematic orientation focused on the study of complex tropical ecosystems and their socio-economic context spells particular challenges to ZMT. The researchers and the management of the Centre recognise that indispensible scientific publications are not enough and that additional outreach efforts are needed to ensure its long-term mission is understood and generates the expected benefits in and beyond the science community.

It is in this context that the Director of ZMT, Prof. Dr. Hildegard Westphal, invited Dr. Cornelia E Nauen of Mundus maris to give a talk to interested researchers reflecting on the critical engagement experiences of the non-profit association and their scientific underpinning. Dr. Bevis Fedder, in charge of Science (knowledge) Management, introduced the talk that took place 22 October 2014 in the ZMT premises.

“There is something profoundly wrong with the way we are living today. There are corrosive pathologies of inequality all around us ... These are reinforced by short-term political actions and a socially divisive language based on the adulation of wealth.

A progressive response will require not only greater knowledge about the state of the planet and its resources, ... We will need a more ethical form of public decision-making based on a language in which our moral instincts and concerns can be better expressed.” These quotes are from the introduction by Prof. Jacqueline McGlade, then Executive Director of the European Environment Agency in Copenhagen, to the second volume of the report Late (societal) lessons from early (scientific) warnings". They formed the context to the talk and helped focus attention on how to manage change successfully in complex and dynamic situations.

A progressive response will require not only greater knowledge about the state of the planet and its resources, ... We will need a more ethical form of public decision-making based on a language in which our moral instincts and concerns can be better expressed.” These quotes are from the introduction by Prof. Jacqueline McGlade, then Executive Director of the European Environment Agency in Copenhagen, to the second volume of the report Late (societal) lessons from early (scientific) warnings". They formed the context to the talk and helped focus attention on how to manage change successfully in complex and dynamic situations.

Why are lessons from early warning so often ignored? Among the most obvious reasons is that formal risk assessments of rapide technological innovations are typically based on a narrow definition of risk which fails to address systemic features and complex interactions. This leads to excessive confidence and undermines mandated application of precautionary principles. Harm to people and the environment gets prolonged and acted upon only belatedly, if at all.

Another major reason is what economists call the externalisation of costs. This happens usually at the expense of common goods, such as climate, pollution of the land, the air and the ocean. In other words, prices charged do not reflect the true production and marketing costs. Profits are privately appropriated, while costs, particularly long-term damage, are forced on the public.

Overfishing and the dramatic decline in marine ecosystems are a case in point. The public in many industrialised countries pays twice, once through hefty subsidies to the perpetrators and a second time by paying higher prices for increasingly scarce fish. Fraud, such as common misdeclaration of one species for another one, whose population has collapsed under the weight of overfishing and/or destruction of its habitat or natural food supply, only aggravates the global trend.

Overfishing and the dramatic decline in marine ecosystems are a case in point. The public in many industrialised countries pays twice, once through hefty subsidies to the perpetrators and a second time by paying higher prices for increasingly scarce fish. Fraud, such as common misdeclaration of one species for another one, whose population has collapsed under the weight of overfishing and/or destruction of its habitat or natural food supply, only aggravates the global trend.

Responsible ways to govern change look differently. Michael Fullan has distilled some five key principles further discussed during the talk.

- Moral purpose – closing the gap between high and lower performing social groups

- Understanding the process of change

- Improving relationships

- Creating knowledge

- Sharing and coherence making.

Examples were given e.g. from practice by Mundus maris to illustrate the principles, many of which are also elaborated upon on the website.

The principles have been shown to have validity well beyond the original field of exploratory research in schools and companies. But it is important to avoid mechanistic application. In other words, when dealing with complex change processes, all of them need to inform planning and doing at all times, but in context-specific ways.

Giving the public easy access to scientific information is an essential step, as e.g. done in the landmark scientific internet archive on all fish species known to science, FishBase. The overall challenge goes well beyond communicating research results, particularly if delivered in a broadcasting mode.

Enhancing the contribution of research to successful change management in different societies requires listening to all voices, suspending judgement until more clarity is achieved, building of trust and critical engagement. Participatory methods, such as "Art of hosting conversations that matter", are particularly suitable to create mutual respect among different stakeholders, and shared understanding that enables collaborative action. The potential for collective learning from the sciences, the arts, practice and traditional cultures, to name but the major sources of knowledge and learning, is huge. The diversity creates the robust learning ecology we need to navigate the troubled waters of today's stressed ocean and the human societies that depend on it - that means all societies and all humanity.

All fotos by Cornelia E Nauen. The slides of the talk can be downloaded here.