Preparation and context of the exhibition

The countless festivities of the Bicentenary of Latin American independence from former colonial powers are a great reminder of how much our histories are intertwined and cast long shadows until today, even when we now look at some of those relatively recent developments through different glasses. There is certainly more to be recorded than political and economic developments, important though they are for the course of history and our contemporary lives.

We (Mundus maris) were asked by CERCAL, the Centre for Latin America Studies at the Free University of Brussels (ULB), to develop an exhibition that would strengthen the interdisciplinary character of an international colloquium, they were organising in collaboration with the Belgian Federal Public Service for Foreign Affairs and supported by the Spanish Presidency of the European Union and others, to commemorate the Bicentenary of Latin American independence. The title of the Colloquium was "¡Libertad! Latin America/Caribbean and Europe - From Common Roots towards an Alliance for the 21st Century" and was scheduled to take place in the Egmont Palace II in Brussels, Belgium, 11 - 12 February 2010. The event was also a contribution towards the 175 anniversary celebrations of the Free University of Brussels.

The colloquium was intended to explore historical, political, socio-economic perspectives and looked for new cross-fertilisation between different fields of enquiry. The environmental dimension of past and future relations between Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe were only addressed in passing. The exhibition in response to the invitation can not come near towards filling this gap. It can only be an opportunity to signal that it is necessary to pay attention to the all-encompassing nature of which our societies on both sides of the Atlantic are part. As Mundus maris, we naturally place particular attention to the Seas, to which we owe our lives and which were also the route by which the European explorers first met Latin America.

The development of the exhibition centered on being an unassuming reminder that the physical, biological and social world of 200 hundred years ago holds some noteworthy lessons for us today. At least we believe it does, as we ask ourselves how to turn the corner towards more sustainable ways of living and sharing the one planet we have. We would like to ensure that our children and grand children can still (or again) enjoy some of the beauty and diversity that has been lost to pressures fed by human demography and unsustainable production and consumption patterns.

The development of the exhibition centered on being an unassuming reminder that the physical, biological and social world of 200 hundred years ago holds some noteworthy lessons for us today. At least we believe it does, as we ask ourselves how to turn the corner towards more sustainable ways of living and sharing the one planet we have. We would like to ensure that our children and grand children can still (or again) enjoy some of the beauty and diversity that has been lost to pressures fed by human demography and unsustainable production and consumption patterns.

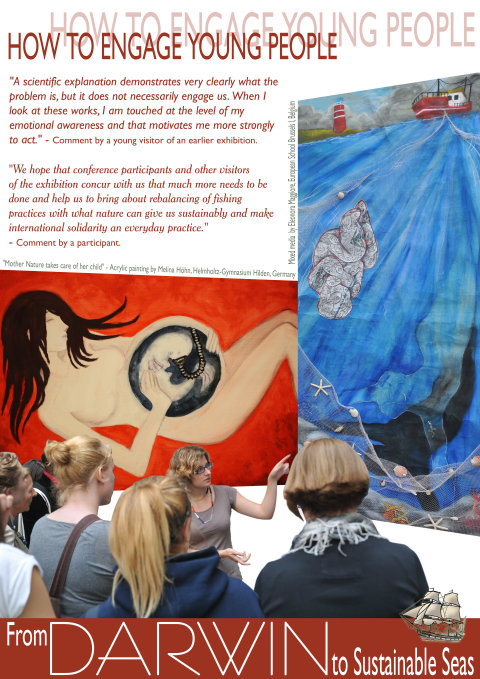

The International Initiative 'Mundus maris – Sciences and Arts for Sustainability' is precisely focused on bringing different strands of human knowledge and search for sustainable relations with our natural and social environments together. It proposes doing so in ways that recognise us as part of nature and strive to engage schools and young people in this quest. We observe that doing science without critical engagement with society creates long delays in making scientifically validated knowledge available to societies at large. A strong social and ethical context for scientific enquiry is also the most robust way to avoid or at least reduce negative unintended consequences that can otherwise arise and are already manifest. The painting of Melina Höhn of Helmholtz-Gymnasium Hilden, Germany, is entitled 'Mother Nature cares for her child' and is an artistic reaction following confrontation of results of scientific research.

The combination with the arts, aesthetic education, respect for and interaction with traditional ecological knowledge in different societies and implicit forms of knowledge form a richer and more robust foundation for developing cooperation based on mutual interest, respect and benefit across generational, physical, political and other boundaries.

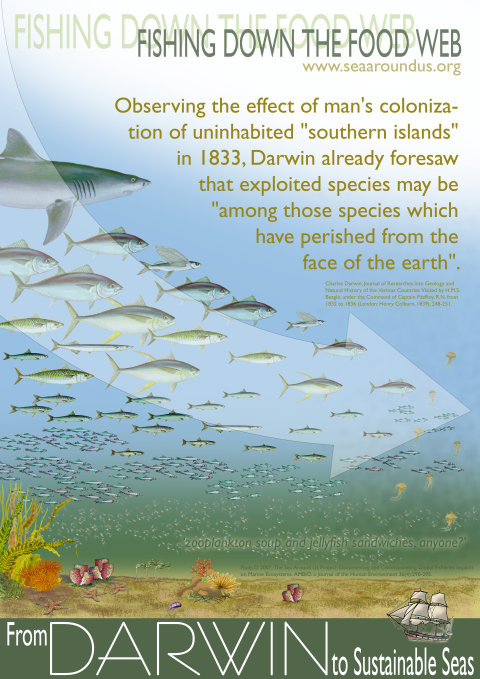

This exhibition places emphasis on the exemplary qualities of Charles Darwin, who was born in the period marking the independence of Latin American countries. His modern inquisitive and open-minded approach has still much to teach us today. He already voiced concerns that overexploitation may threaten the survival of marine life and humans in the southern cone. Little could he know though how deeply the onslaught of advanced technologies, a bit more than a century on, would affect marine and coastal ecosystems and their human dwellers.

The posters of this exhibition show only some facets of how scientific understanding has evolved 'standing on the shoulders of giants' such as Darwin. It also illustrates that it is possible to take the science outside the expert circles – very much into the public arena, where it was during Darwin's time – and engage artists and schools with their young people.

Engaging here is intended as sharing knowledge at different levels, inviting own critical enquiry and expression. Engaging is also intended not to stop at diagnosis, but cooperate around sustainable alternatives to the profound crisis in nature and society that affects us all. We are not all affected in quite the same way, we are strung together in more ways than most of us realise in their daily lives. This is apparent from the research and also experienced by the young people joining the journey. We are inviting visitors to join as well and contribute their perspectives and active solidarity on the next steps of this journey.

The following poster exhibition was first put on display in the context of the international interdisciplinary colloquium "¡Libertad! - Latin America/Caribbean and Europe - From Common Roots Towards an Alliance for the 21st Century", Palais d'Egmont II, Brussels, Belgium, 11 - 12 February 2010.

Charles Darwin (CD) studied South American natural history with rigour and a more open mind than many of his contemporaries. What were contributing factors considering that outstanding people are never self-made, but the result of favourable context, hard work and opportunity?

Charles Darwin (CD) studied South American natural history with rigour and a more open mind than many of his contemporaries. What were contributing factors considering that outstanding people are never self-made, but the result of favourable context, hard work and opportunity?

Among the early forming experiences was his relationship with John Edmonton, "a former South American slave of African ancestry established in

Edinburgh, from whom CD took private lessons in taxidermy... it appears to have opened his mind to respecting people outside his narrow class and ethnic background, thus enabling him to learn from the people he met in his later travels and readings, and, ultimately, to formulate a theory that encompassed all of

humanity, and embedded us within the same nature. This contrasts with the divisive schemes propagated by less open-minded contemporaries, e.g. Louis Agassiz and Richard Ower, whose religious prejudices, combined with social opportunism, ultimately

undermined their science.(1)

This open-mindedness made it possible for CD to report all that he observed, as he did in his narrative, without prejudice. He was awestruck with the nature (encompassing plants and animals, including insects and humans) that greeted him in South America. His open mind imbibed, assembled, catalogued and later analysed all that he observed. The completeness of his entire scientific work can certainly be attributed in no small manner to the fact that he catalogued everything (including anthropological accounts). During that period, he was the first of his contemporaries to do so. Indeed, he probably started this way of reporting, which is very useful to us today.

Throughout his long and productive life, CD demonstrated a deep understanding of the relationship between observed facts and theory. He was constantly searching for the underlying principles that strung the otherwise isolated facts arising from observations, experiments, reading and exchanges with other people together in a coherent way. It is this critical and probing attitude that still serves us in good stead today.

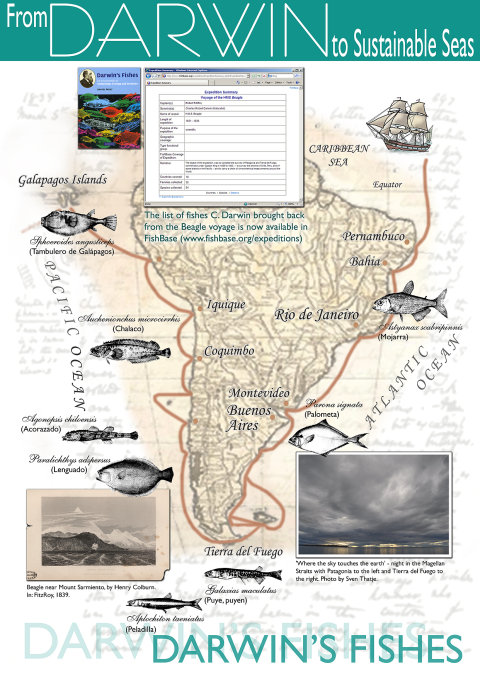

(1) Pauly, D., 2004. Darwin's Fishes. Cambridge University Press, 340 p.

This poster illustrates just a small selection of associations that are conjured up when giving the name of a fish – in this case the emblematic Peruvian anchoveta – Engraulis ringens(by its scientific name).

This poster illustrates just a small selection of associations that are conjured up when giving the name of a fish – in this case the emblematic Peruvian anchoveta – Engraulis ringens(by its scientific name).

Among the most obvious are the long historical use of this key stone species in the Peruvian upwelling ecosystem, its value in cultural practices and representations, but also the importance for employment, coastal and industrial offshore fishing, processing and the money made and lost in this industry.

The anchoveta is also what kept the guano birds happy and breeding and thus formed the basis of a once profitable saltpetre and fertiliser industry in Peru and northern Chile.

Last, but not least, the anchovy and the ecosystem in which it is embedded attracted extensive biological study, which documented its meteoritic rise to 13 million tons in 1972 as the biggest catch in the world until its collapse from a combination of overfishing and an El Niño event. It has become abundant again, in the nineties, but remains vulnerable to similar constellations as can be seen from Peruvian catches as updated in the Sea Around Us Project in 2010.

Do you see the delicate ceviche on the poster? What about introducing anchovies into the human diet rather than reducing it to fishmeal for piggeries and salmon farming? For one, it would create tremendous added value for the Peruvian and Chilean economies. See the video of Daniel Pauly suggesting just that.

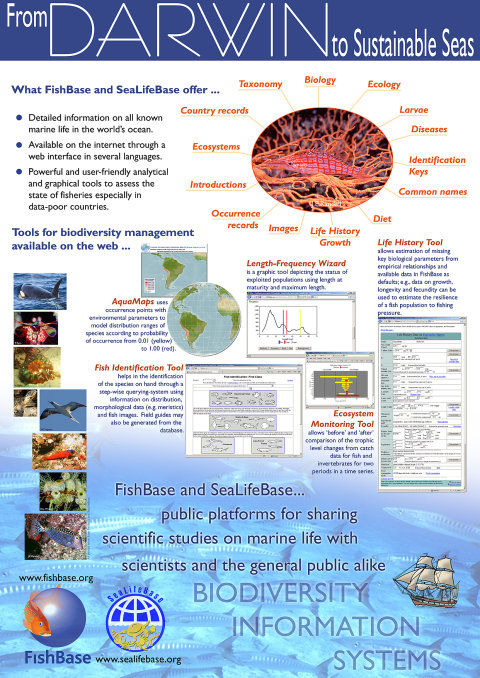

FishBase and SeaLifeBase are public, web-based, global archives of published data on nomeclatural, geographic, biological, ecological and traditional knowledge on aquatic organisms.

Created 20 years ago to support fisheries management with sound scientific knowledge, FishBase has evolved into a biodiversity information system on all fishes on earth (roughly 31,000 species). With more than one million visits per month on the web, it serves many user groups for different purposes through interfaces in 21 languages and 8 mirror sites.

Created 20 years ago to support fisheries management with sound scientific knowledge, FishBase has evolved into a biodiversity information system on all fishes on earth (roughly 31,000 species). With more than one million visits per month on the web, it serves many user groups for different purposes through interfaces in 21 languages and 8 mirror sites.

AquaMaps uses occurrence points with environmental parameters to model distribution ranges of species according to probability of occurrence from 0.01-1.00;

The Fish Identification tool helps in the identification of the species on hand through a step-wise querying system using information on distribution, morphological data (e.g., meristics) and fish images. Field guides may also be generated using this structure.

The Ecosystem Monitoring tool allows ‘before’ and ‘after’ comparisons of the trophic level changes from catch data for fish and invertebrates for two periods in a time series.

The Life History tool allows estimation of missing key biological parameters from existing data. It gives an idea of a fish species or population’s resilience to fishing pressure.

The Length-Frequency wizard provides a graphic representation of the status of exploitation of a population.

The much younger SeaLifeBase, built using the FishBase platform in 2006, is attempting to duplicate the FishBase feat for non-fish marine organisms of all the earth’s oceans. Supported with FishBase’s 20 years of expertise and Catalogue of Life’s authoritative taxonomic backbone, enhanced by the World Register of Marine Species, SeaLifeBase was able to collect information for more than 80,000 marine organisms within its first 2 years.

Both FishBase and SeaLifeBase maintain networks of almost 2,000 collaborators worldwide. As data providers, both information systems contribute to many international initiatives and national programmes, for example, the Catalogue of Life, the Barcode of Life, the Encyclopedia of Life, GenBank, the IUCN, the Sea Around Us Project and many others.

FishBase is piloted and SeaLifeBase is endorsed by an international consortium of 9 institutions:

- Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France;

- Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren, Belgium;

- Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden;

- Institut für Meereskunde, Kiel, Germany;

- the WorldFish Center,Los Baños, Philippines;

- FAO, Rome, Italy;

- the Fisheries Centre of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada;

- School of Biology in the Department of Zoology, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece;

- Chinese Academy of Fisheries Science, Beijing, China.

The financial support for the development stages of FishBase came from the European Commission.

Observing the lush South American nature around him, Darwin saw the value of kelp forests as home to a wide range of life and writes “[…] I can only compare these great aquatic forests of the southern hemisphere with the terrestrial ones in the intertropical regions. Yet if in any country a forest was destroyed, I do not believe nearly so many species of animals would perish, as here from the destruction of the kelp. Amidst the leaves of this plant numerous species of fish live, which nowhere else could find food or shelter; with their destruction the many cormorants and other fishing birds, the otters, seals, and porpoises, would soon perish also; and lastly, the Fuegian savage, the miserable lord of this miserable land, would redouble his cannibal feast, decrease in numbers and perhaps cease to exist. (1)

Beyond the specific case, scientists have documented the dramatic effects fisheries have had on marine and coastal ecosystems around the world in an accelerated way in the last 50 to 100 years. What we study today, is usually a shadow of its former self. In the North Atlantic, a data-rich region for such analyses, biomasses of large predators, which are often key to keeping ecosystems productive, are between 5 and 10% of what they were 100 years ago. (3)

It is becoming apparent that if biomasses of important species in the food web get depressed below 20% of their original density for protracted times, the functioning of the ecosystem and its ability to regenerate to earlier states is severely jeopardised. (4)

(1) Darwin, C. 1846. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, Under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. Vol. 1. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 309-310.

(2) Tegner, M.J. And P.K. Dayton, 2000. Ecosystem effects of fishing in kelp forest communities. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 57:579-589.

(3) Christensen, V., S. Guénette, J.J. Heymans, C.J. Walters, R. Watson, D. Zeller and D. Pauly, 2003. Hundred-year decline of North Atlantic predatory fishes. Fish and Fisheries, 4:1-24.

(4) Froese, R. and A. Proelß, 2010. Rebuilding fish stocks no later than 2015: Will Europe meet the deadline? Fish and Fisheries, DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00349.x

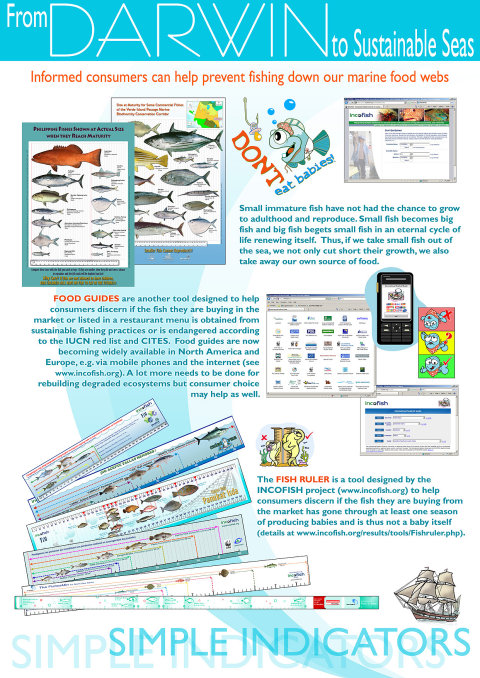

No university education is needed to understand that fishing baby fish which have not been able to grow to a size where they can reproduce at least once can not be sustainable. But how do we know whether we have a baby fish in front of us in the net or in the market?

No university education is needed to understand that fishing baby fish which have not been able to grow to a size where they can reproduce at least once can not be sustainable. But how do we know whether we have a baby fish in front of us in the net or in the market?

Thanks to FishBase you can look up that minimum size 'at first maturity' for all fishes used by humans and for the full range of temperatures in which they survive and which influence how they grow. Not everybody knows as yet about FishBase or has access to the internet all the time.

Thanks to the INCOFISH research project, posters and fish rulers for common fishes have been developed and disseminated in several countries to help people identify this minimum length even if there is no access to the internet. A selection of these is shown here – such activities have been particularly sustained in Peru and amplified in Germany thanks to a media campaign of a consumer protection agency, using the research results.

Food guides are another tool designed to help consumers discern if the fish they are buying in the market or listed in a restaurant menu is obtained from sustainable fishing practices or is endangered according to the IUCN red list and CITES.

Food guides are now becoming widely available in North America and Europe, for example, via mobile phones and the internet. A lot more needs to be done for rebuilding degraded ecosystems, but consumer choice may help as well.

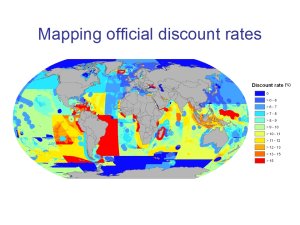

There are also little-noted, yet major economic factors at work. They have been described and analysed by Rashid Sumaila and others, e.g. economic behaviour that discounts the future too much, taking small benefits now at the expense of future benefits and even putting the productiveness of ecosystems into jeopardy.

In a nutshell, it goes like this:

- When we take too much and too small fish out of the sea, we are really grabbing a small benefit today, because we do not wait for the fishes to grow a little bigger to produce a much bigger benefit.

- Economists call that a discount rate. It is like a negative interest rate on a capital to harvest in the future. If we use a high discount rate, it makes more sense not to wait and get a much lower, but immediate gain. Conversely, if the discount rate is low, it makes sense to invest long-term into the future.

- When we invest in the education and well-being of our children today and for many years, we do that even if they do not get a big material value out of it. Yet we may even constrain our own consumption today so that our children can live well tomorrow because as parents, we do not count our children’s future incomes as ours.

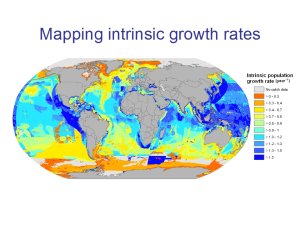

In largely public spaces such as the sea, economic operators can be irresistibly tempted to overexploit, especially if banking interests (the ‘other side of the coin’ of discounting) are much higher than nature’s intrinsic capacity for renewal. In such areas of the world, it is particularly important to create large marine protected areas (MPA) as an insurance policy for future benefits. The world maps compare the two. MPAs are particularly important, where discount rates are in the orange to red (from Sumaila, 2009).

In largely public spaces such as the sea, economic operators can be irresistibly tempted to overexploit, especially if banking interests (the ‘other side of the coin’ of discounting) are much higher than nature’s intrinsic capacity for renewal. In such areas of the world, it is particularly important to create large marine protected areas (MPA) as an insurance policy for future benefits. The world maps compare the two. MPAs are particularly important, where discount rates are in the orange to red (from Sumaila, 2009).

Other factors come into play as well. When governments hand out subsidies to lower the cost of fuel, boat building, and efficiency increases, they enable fishing operations well beyond what the ecosystems we know can sustainably support.

These subsidies have been estimated by the World Bank at US$ 11 billion/year in Asia, US$ 5 billion in Europe and US$ 4.5 billion in Latin America and the Caribbean. Not all subsidies are bad. Exceptions are those increasing safety at sea or help fishers or their children find meaningful alternative employment and reduce the fishing.

These subsidies have been estimated by the World Bank at US$ 11 billion/year in Asia, US$ 5 billion in Europe and US$ 4.5 billion in Latin America and the Caribbean. Not all subsidies are bad. Exceptions are those increasing safety at sea or help fishers or their children find meaningful alternative employment and reduce the fishing.

All this goes to show that consumer choice can be important, but it alone can not solve these deeper problems.

Source of economic analyses: Sumaila, U.R., 2009. Economics for sustainable oceans: Science for empowering solutions. Presentation to the EU Sustainability Conference, 27 May 2009, Brussels, Belgium.

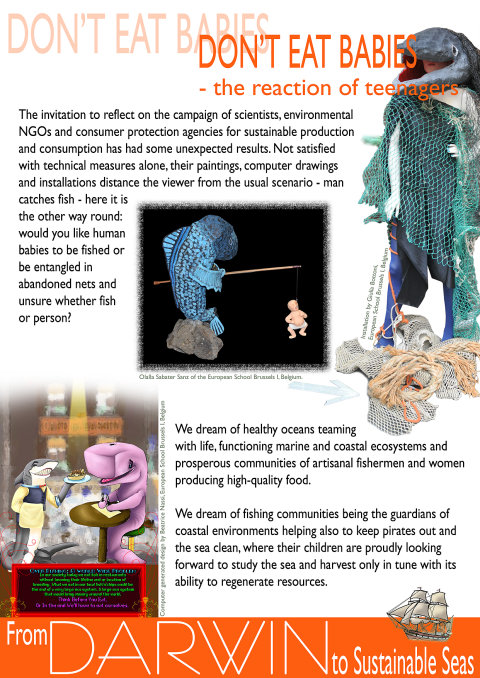

When confronted with these scientifically documented facts, the reaction of teenagers at the European School in Brussels I, Belgium, was initially shock about the gravity of the state of degradation of coastal ecosystems in many parts of the world. Then came the question, what to do to draw attention to this state of affairs so that it stops.

The invitation to reflect on the campaign of scientists, environmental NGOs and consumer protection agencies for sustainable production and consumption has had some unexpected results. Not satisfied with technical measures alone, their paintings, computer drawings and installations distance the viewer from the usual scenario – man catches fish – here it is the other way around: would you like human babies to be fished or be entangled in abandoned nets and unsure whether fish or person?

When confronted with these scientifically documented facts, the reaction of teenagers at the European School in Brussels I, Belgium, was initially shock about the gravity of the state of degradation of coastal ecosystems in many parts of the world. Then came the question, what to do to draw attention to this state of affairs so that it stops.

When confronted with these scientifically documented facts, the reaction of teenagers at the European School in Brussels I, Belgium, was initially shock about the gravity of the state of degradation of coastal ecosystems in many parts of the world. Then came the question, what to do to draw attention to this state of affairs so that it stops.

The invitation to reflect on the campaign of scientists, environmental NGOs and consumer protection agencies for sustainable production and consumption has had some unexpected results. Not satisfied with technical measures alone, their paintings, computer drawings and installations distance the viewer from the usual scenario – man catches fish – here it is the other way around: would you like human babies to be fished or be entangled in abandoned nets and unsure whether fish or person?

We dream of healthy oceans teaming with life, functioning marine and coastal ecosystems and prosperous communities of artisanal fishermen and women producing high-quality food.

We dream of healthy oceans teaming with life, functioning marine and coastal ecosystems and prosperous communities of artisanal fishermen and women producing high-quality food.

We dream of fishing communities being the guardians of coastal environments helping also to keep pirates out and the sea clean, where their children are proudly looking forward to study the sea and harvest only in tune with its ability to regenerate resources.

We dream of intact corals and mangroves neither threatened by global warming nor by pollution or indiscriminate cutting - natural protections of the coastlines in balance with ecological and human needs.

We dream of harnessing the power of the waves for clean energy while maintaining the awe and beauty of nature.

We dream of studying the sea around us, trying to understand more of the dynamics of its currents that heat Europe through the Gulf Stream, well-up nutrient-rich water off West Africa, Peru and Chile and circulate in huge conveyor belts which connect even the most far-flung corners.

And work together so that the dream does not turn into a nightmare.

In this spirit the Arts Working Group (now Working Group for Science and Arts for Sustainability) of the Helmholtz-Gymnasium Hilden, Germany, wanted to capture the beauty and the love for the sea, but also the fragility in their exploration of artistic photography.

More of their works is shown in the occasion of an exhibition with other schools and professional artists in 2009 entitled “Sustainable Seas Through the Eyes of Art”.

The mix of anguish, anger, beauty and hope expressed in these works is intended to provoke feelings not so easily triggered by reading a scientific publication. They take inspiration from the science, yet engage also at the emotional level.

The mix of anguish, anger, beauty and hope expressed in these works is intended to provoke feelings not so easily triggered by reading a scientific publication. They take inspiration from the science, yet engage also at the emotional level.

The aesthetic reflection on the scientific findings and concepts is opening additional avenues to take in the findings and invite visitors to explore for themselves, at least not to remain indifferent.

This short journey tracing the links between Europe and Latin America from the perspective of our relationship to the sea starts with the scientific study so decisively advanced by Charles Darwin.

This short journey tracing the links between Europe and Latin America from the perspective of our relationship to the sea starts with the scientific study so decisively advanced by Charles Darwin.

It draws our attention to the fact that the same name – here of the famous Peruvian anchoveta – conjures up many different ways of knowing and experience. It takes us to the frontier of marine sciences today and the efforts to make the science more readily accessible to everybody and to create a level playing field for all through public repositories of knowledge which are readily accessible in many languages and through many ways of questioning.

We look for new syntheses between sciences and artistic expression to appeal to a wider range of human perceptions and needs. This is also a way to engage with young people and encourage them to engage for sustainable seas.

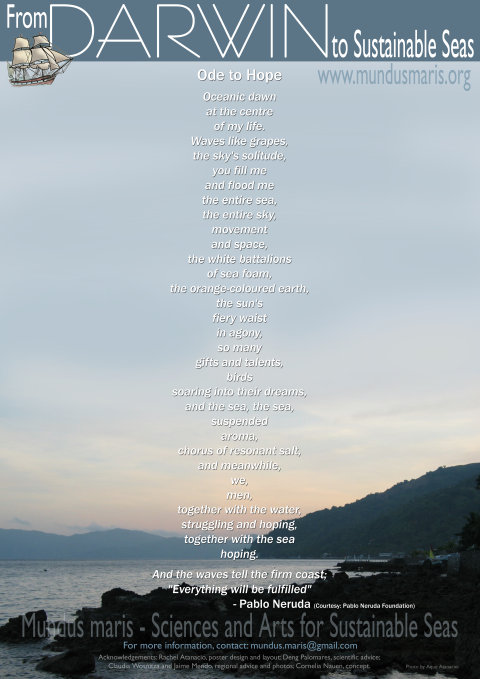

We could not have concluded this journey without a homage to the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda who had a house by the sea and wrote this poem 'Ode to hope'.

The critical enquiry and deep humanistic expression of these two great spirits can be beacons for our own search for a new relationship with the sea and the people of our two continents. The poem is reproduced here thanks to the courtesy of the Pablo Neruda Foundation.

Ode to Hope

Oceanic dawn

Oceanic dawn

at the centre

of my life.

Waves like grapes,

the sky's solitude,

you fill me

and flood me

the entire sea,

the entire sky,

movement

and space,

the white battalions

of sea foam,

the orange-coloured earth,

the sun's

fiery waist

in agony,

so many

gifts and talents,

birds

soaring into their dreams,

and the sea, the sea,

suspended

aroma,

chorus of resonant salt,  and meanwhile,

and meanwhile,

we,

men,

together with the water,

struggling and hoping,

together with the sea

hoping.

And the waves tell the firm coast;

"Everything will be fulfilled"

Pablo Neruda

This poster exhibition was created as part of the international collaboration between scientists, artists and schools enabled through the Mundus maris Initiative. Most of the additional information contained in the companion guide to the exhibition is reproduced next to each poster.

For more information look at other parts of this website or contact Cette adresse e-mail est protégée contre les robots spammeurs. Vous devez activer le JavaScript pour la visualiser.

For financial support of the work with schools for sustainable seas and cultural diversity, transfer your financial contribution to

Special account Mundus maris - IBAN: BE54 0688 9178 6297 - BIC/SWIFT: GKCCBEBB

Credits:

Rachel Atanacio, graphic design of posters;

Deng Palomares, scientific advice;

Claudia Wosnitza and Jaime Mendo, regional advice and photos;

Cornelia E. Nauen, concept.