Mare nostrum

Seeing the extent of the Roman Empire at the time of its maximum expansion immediately clarifies the reason why the Mediterranean was defined Mare nostrum at the time.

Seeing the extent of the Roman Empire at the time of its maximum expansion immediately clarifies the reason why the Mediterranean was defined Mare nostrum at the time.

The vastness of the sea was certainly seen by the first human beings as a barrier, but already in the protohistoric era it was gradually transforming itself into a means of union, as a transmission way not only of goods, but also of culture and human knowledge.

We addressed that already in an earlier article, but now we return to the subject.

It is even possible that virtuous examples from antiquity indicate the way for a better use of human and environmental resources.

However, we must first complete the information with this map of the main land routes of the empire. With a touch of originality it was drawn up on the example of the subways of today's metropolises (it can be found in various sites, we point out one here)

However, we must first complete the information with this map of the main land routes of the empire. With a touch of originality it was drawn up on the example of the subways of today's metropolises (it can be found in various sites, we point out one here)

The complex land communication system was complementary to the maritime routes and allowed the movement of men, women and goods.

Knowledge travelled as well, of course.

Who were the people who worked and lived in an ancient port? From the findings of the port necropolis we know that they came from every part of the empire.

Among them there were of course shipowners, merchants, but above all specialised workers.

Among them there were of course shipowners, merchants, but above all specialised workers.

The findings of the necropolis of Portus tell us a lot about these people: we find the graves of sailors, naturally, but also of doctors, tax collectors, messengers, officials, soldiers, guardians.

And more builders and shipyard workers, stevedores, warehouse workers...

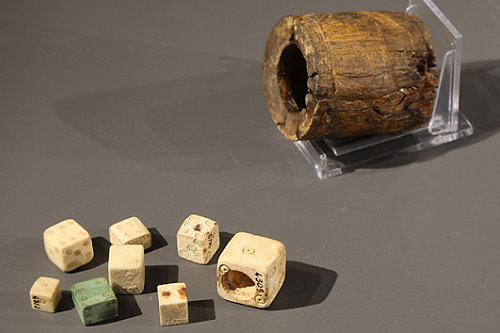

And as in all ports, in every sea, in every era, people were not always at work. They allowed themselves moments of leisure and were not necessarily saints. Among the numerous finds from the port area is this group of playing dice with their container for throwing. One of the dice is drilled for inserting a weight that allows it to be rigged. Among the numerous objects of daily use found in the area and exhibited at the Museo delle Navi is also this small hand scale.

Among the numerous objects of daily use found in the area and exhibited at the Museo delle Navi is also this small hand scale.

Perhaps it was used to weigh some of the fish caught in the area, where the fishing port of Rome is still located.

Perhaps some of the ones depicted in the mosaics on display.

Moreover, Rome itself is extremely well endowed with finds of representations of this kind, both in mosaic and in fresco.

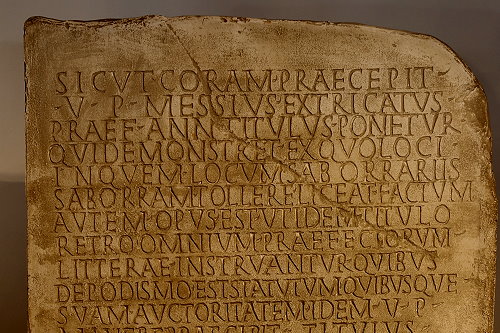

A plaque found at the port of Claudio tells us something different, something important.

A plaque found at the port of Claudio tells us something different, something important.

«As officially prescribed by the prefect of the annona Messio Estricato, vir perfectissimus, a plaque should be placed indicating from which area it is permissible for the saborrarii (ballasters) to take sand. The ordinances of each prefect reporting the extension of the area, ordinances still in force, as provided for by the vir perfectissimus, are reported on the back of the tombstone.

The plaque was engraved on behalf of Marco Vergunteio Vincitore through Giulio Materno centurion frumentario, the fifteenth day before the calends of October, consuls Faustino and Rufino»»

The date shown at the bottom of the tombstone corresponds to 17 September 210 a.D. Evidently an environmental awareness already existed at the time: the one that is too often lacking today.

But it's time to move on to an even more important topic. The ports of the capital of the Roman Empire obviously deserve our attention.

But it's time to move on to an even more important topic. The ports of the capital of the Roman Empire obviously deserve our attention.

But with which other ports were they connected? What was the network of contacts and commerce that spread out from the ports of Ostia?

We are provided with an initial answer by the Piazzale delle Corporazioni. As we have seen it is located in the central part of Ostia Antica. It is a vast square surrounded by arcades and shops.

Floor mosaics, still well preserved, showed the company name in front of the entrance and often the port or ports to which it offered a connection.

Here we see the sign of the navicularia (shipping company) which ensured the connection with the port of Carthage, located in what is now the Gulf of Tunis, in northern Africa.

We will develop this new topic on the next page.