In the video available to visitors to the Fiumicino Ship Museum next to Rome's international airport, the archaeologist Renato Sebastiani states that without the ancient port of Ostia the greatness of imperial Rome would not have been possible, a metropolis of about one million inhabitants. Certainly a statement that can be shared, but it is only one side of a coin that seems to have many, well more than two. And here we have to open a necessary digression.

In the video available to visitors to the Fiumicino Ship Museum next to Rome's international airport, the archaeologist Renato Sebastiani states that without the ancient port of Ostia the greatness of imperial Rome would not have been possible, a metropolis of about one million inhabitants. Certainly a statement that can be shared, but it is only one side of a coin that seems to have many, well more than two. And here we have to open a necessary digression.

Ostia (from ostium i.e. mouth, gate, entrance) was founded by King Ancus Marzius in the 7th century BC: his descendant Quintus Marcius Rex (surname left to the members of the family) built the Aqua Marcia aqueduct 500 years later, issuing a coin that shows Ancus Martius on the obverse and the aqueduct on the reverse.

Ostia (from ostium i.e. mouth, gate, entrance) was founded by King Ancus Marzius in the 7th century BC: his descendant Quintus Marcius Rex (surname left to the members of the family) built the Aqua Marcia aqueduct 500 years later, issuing a coin that shows Ancus Martius on the obverse and the aqueduct on the reverse.

This is further confirmation of a theorem never sufficiently appreciated and disseminated: Civilizations are born from the sea, and from water. Destroyed by the barbarian invasions in 572 a.D. the Acqua Marcia aqueduct was restored and reactivated in 1872. It is still in operation and supplies one of the most appreciated drinking water sources in Rome after about 2200 years.

We can expand on Sebastiani's statement: Rome would never even have been founded without the sea, nor would it have ever grown great without water. The first agglomeration was in fact established in the eighth century BC near the meeting place of three different ethnic groups divided by as many rivers.

We can expand on Sebastiani's statement: Rome would never even have been founded without the sea, nor would it have ever grown great without water. The first agglomeration was in fact established in the eighth century BC near the meeting place of three different ethnic groups divided by as many rivers.

The Etruscans lived on the right side of the Tiber, the Sabines occupied the territory between the Tiber and its tributary Aniene, the Latins lived on the left sides of the Aniene and the Tiber.

Among the exchanges of the three peoples who had decided to make water a meeting point and not a separation point, salt was the primary commodity: it came from the nearby coast, about 15 km as the crow flies. It was extracted in the Etruscan area, transported to Rome along the river or along the road which, until a century ago, was still called via della Salara Vecchia, then forwarded to the internal territories of Central Italy along what is still called via Salaria today.

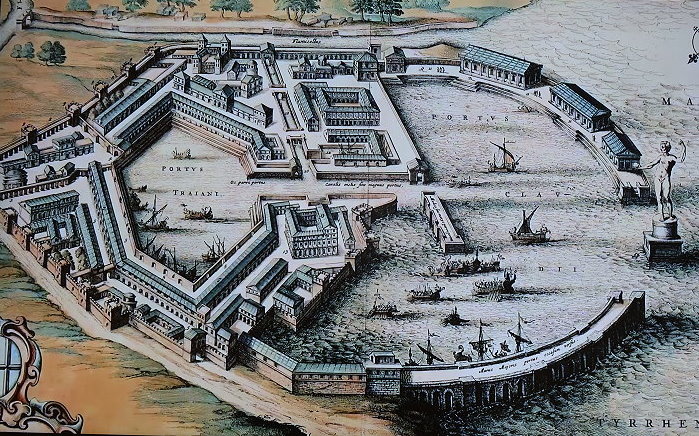

The foundation of Ostia, which happened in a later period, had the purpose of providing Rome with a port near the mouth of the Tiber, to transport foodstuffs to Rome by river boats, but also to put an end to the Etruscan monopoly on the extraction of salt. In the following centuries Ostia expanded to adapt to the growth of Rome. In the imperial era, two new grandiose ports were built to cope with the growing traffic: in the middle of the first century BC by the emperor Claudius and about 70 years later by Trajan. The complex simply took the name of Portus.

The sediments transported by the Tiber made the coastline advance over the centuries: both Ostia and Portus found themselves more and more inland and were abandoned.

The sediments transported by the Tiber made the coastline advance over the centuries: both Ostia and Portus found themselves more and more inland and were abandoned.

The ruins of what is now called Ostia Antica offer visitors a spectacular insight into life 2,000 years ago, comparable to that offered by Pompeii.

The port of Trajan, an immense magnificent hexagonal structure, can also be visited.

The port of Claudius has instead sunk underground and only a few ruins are visible today.

During the construction work on the airport at the end of the 1950s, the remains of some boats also emerged.

Three types of boats were recovered:

Three types of boats were recovered:

A small sailing boat called 'onoraria':

This was an open sea cargo vessel.

Three 'naves caudicaria':

river barges that transhipped goods to Rome.

The caudicarius was someone who placed a deposit. Perhaps the barges were called like this because the transporter could redeem the deposit upon showing the receipt of the addressee of the merchandise.

And a fishing boat:

called Fiumicino 5

We are about to talk more about it. But we shall not just talk about that boat.

Fiumicino 5

Fiumicino 5

Fiumicino 5 was a 'vivaria', i.e. a boat equipped with a container full of water in which to keep the catch live in optimal conditions. It is probable that these boats were used to carry goods directly to Rome.

With the progressive population increase, marine fishing had become insufficient to cover the food needs of the entire population. Fish had thus become a luxury product, reserved for the classes with greater purchasing power residing in the capital.

To make up for this shortcoming, the use of aquaculture gradually increased, both in marine basins and in fresh water, obtaining products with a more affordable price.

Some of the personalities who dedicated themselves to this commercial activity have left unsuspected traces up to the present day: Gaius Sergius Orata (2nd century BC) as well as being considered the inventor of the hypocaust heating system used in spas and luxury homes, was one of the first entrepreneurs to deal with aquaculture. His specialty was oyster farming, but some believe that the prized fish of the same name, Sparus aurata, takes its name from him.

It is also said that the moray eel has had this name in memory of the leader Lucius Licinius Murena (1st century BC) who was the first to breed it.

In the third century, the emperor Diocletian issued the Edictum Diocletiàni de pretiis rerum venalium with which he fixed the selling prices of many necessities, including fish.

In the third century, the emperor Diocletian issued the Edictum Diocletiàni de pretiis rerum venalium with which he fixed the selling prices of many necessities, including fish.

It may be interesting to examine it in detail to find out which were the most widespread and appreciated species at the time.

Naturally, this task is reserved for experts, the only ones able to decipher the terminology used by the ancients for marine species.

For comparison, keep in mind that the edict set the price of a chicken at 30 denarii and that a pondus, or pound, corresponds to about 327 grams.

| piscis aspratilis marini Ital(icum) po(ndo) I | (denarii) viginti quattuor (24) |

| piscis secundi Ital(icum) po(ndo) I | (denarii) sedecim (16) |

| piscis flubialis optimi Ital(icum) po(ndo) unum | (denarii) duodecim (12) |

| piscis secundi flubialis Ital(icum) po(ndo) unum | (denarii) octo (8) |

| piscis salsi Ital(icum) po(ndo) unum | (denarii) sex (6) |

| ostriae n(umero) centum | (denarii) centum (100) |

| echini n(umero) centum | (denarii) quinquaginta (50) |

| echini recentis purgati Italicum s(extarius) unum | denarii) quinquaginta (50) |

| echini salsi Italicum s(extarius) unum | (denarii) centum (100) |

| sphonduli marini n(umero) centum | (denarii) quinquaginta (50) |

| casei sicci Ital(icum) po(ndo) unum | (denarii) duodecim (12) |

| sardae sive sardinae Ital(icum) po(ndo) unum | (denarii) sedecim (16) |

But let's get back to Fiumicino 5.

But let's get back to Fiumicino 5.

This is our live fish transport boat.

As we see, it's a vessel of modest size, not so different from some undecked vessels still in use in small-scale fisheries today, even in industrialised countries.

It is assumed that it had between two and three people onboard, but could almost certainly also be managed by a single person.

The vivarium has numerous holes on the bottom, intended for the exchange of water when necessary.

The vivarium has numerous holes on the bottom, intended for the exchange of water when necessary.

They were otherwise closed by pine wood caps.

The vivarium was equipped with a folding lid, to keep the contents safe, but also probably to prevent the fish from escaping in case of rough seas.

A lot remains to be explored and told starting with the reconstruction to the right.

A lot remains to be explored and told starting with the reconstruction to the right.

More is to be said about the Ship Museum in Fiumicino, the Portus and Ostia and even about much else.

We shall talk about that.

Mare nostrum

Seeing the extent of the Roman Empire at the time of its maximum expansion immediately clarifies the reason why the Mediterranean was defined Mare nostrum at the time.

Seeing the extent of the Roman Empire at the time of its maximum expansion immediately clarifies the reason why the Mediterranean was defined Mare nostrum at the time.

The vastness of the sea was certainly seen by the first human beings as a barrier, but already in the protohistoric era it was gradually transforming itself into a means of union, as a transmission way not only of goods, but also of culture and human knowledge.

We addressed that already in an earlier article, but now we return to the subject.

It is even possible that virtuous examples from antiquity indicate the way for a better use of human and environmental resources.

However, we must first complete the information with this map of the main land routes of the empire. With a touch of originality it was drawn up on the example of the subways of today's metropolises (it can be found in various sites, we point out one here)

However, we must first complete the information with this map of the main land routes of the empire. With a touch of originality it was drawn up on the example of the subways of today's metropolises (it can be found in various sites, we point out one here)

The complex land communication system was complementary to the maritime routes and allowed the movement of men, women and goods.

Knowledge travelled as well, of course.

Who were the people who worked and lived in an ancient port? From the findings of the port necropolis we know that they came from every part of the empire.

Among them there were of course shipowners, merchants, but above all specialised workers.

Among them there were of course shipowners, merchants, but above all specialised workers.

The findings of the necropolis of Portus tell us a lot about these people: we find the graves of sailors, naturally, but also of doctors, tax collectors, messengers, officials, soldiers, guardians.

And more builders and shipyard workers, stevedores, warehouse workers...

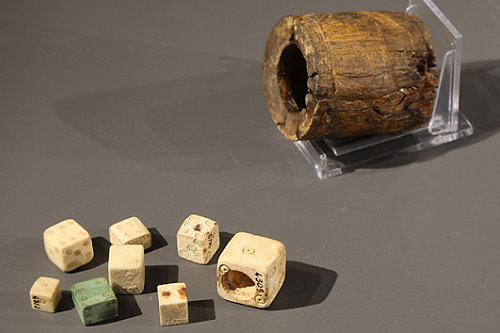

And as in all ports, in every sea, in every era, people were not always at work. They allowed themselves moments of leisure and were not necessarily saints. Among the numerous finds from the port area is this group of playing dice with their container for throwing. One of the dice is drilled for inserting a weight that allows it to be rigged. Among the numerous objects of daily use found in the area and exhibited at the Museo delle Navi is also this small hand scale.

Among the numerous objects of daily use found in the area and exhibited at the Museo delle Navi is also this small hand scale.

Perhaps it was used to weigh some of the fish caught in the area, where the fishing port of Rome is still located.

Perhaps some of the ones depicted in the mosaics on display.

Moreover, Rome itself is extremely well endowed with finds of representations of this kind, both in mosaic and in fresco.

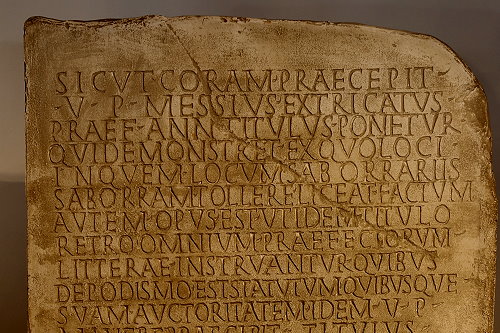

A plaque found at the port of Claudio tells us something different, something important.

A plaque found at the port of Claudio tells us something different, something important.

«As officially prescribed by the prefect of the annona Messio Estricato, vir perfectissimus, a plaque should be placed indicating from which area it is permissible for the saborrarii (ballasters) to take sand. The ordinances of each prefect reporting the extension of the area, ordinances still in force, as provided for by the vir perfectissimus, are reported on the back of the tombstone.

The plaque was engraved on behalf of Marco Vergunteio Vincitore through Giulio Materno centurion frumentario, the fifteenth day before the calends of October, consuls Faustino and Rufino»»

The date shown at the bottom of the tombstone corresponds to 17 September 210 a.D. Evidently an environmental awareness already existed at the time: the one that is too often lacking today.

But it's time to move on to an even more important topic. The ports of the capital of the Roman Empire obviously deserve our attention.

But it's time to move on to an even more important topic. The ports of the capital of the Roman Empire obviously deserve our attention.

But with which other ports were they connected? What was the network of contacts and commerce that spread out from the ports of Ostia?

We are provided with an initial answer by the Piazzale delle Corporazioni. As we have seen it is located in the central part of Ostia Antica. It is a vast square surrounded by arcades and shops.

Floor mosaics, still well preserved, showed the company name in front of the entrance and often the port or ports to which it offered a connection.

Here we see the sign of the navicularia (shipping company) which ensured the connection with the port of Carthage, located in what is now the Gulf of Tunis, in northern Africa.

We will develop this new topic on the next page.

Towards the interior of the country

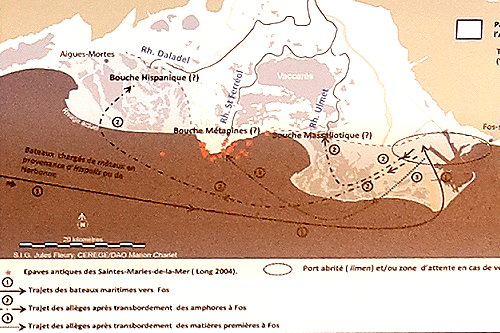

The Naval Museum of Fiumicino has established a collaborative relationship with France, and uses the example of the ancient port at the mouth of the Rhône in the Gulf of Fos-sur-mer, near Marseilles, to give us information on river transport towards the interior.

The Naval Museum of Fiumicino has established a collaborative relationship with France, and uses the example of the ancient port at the mouth of the Rhône in the Gulf of Fos-sur-mer, near Marseilles, to give us information on river transport towards the interior.

In this case, distances inland are much greater than those to be covered from the ports of Ostia since the goods were destined for what was then called Gaul (France and Belgium) and as far as western Germany and Holland.

The Gulf of Fos-sur-mer is located halfway between Spain and Italy and was therefore ideal both as a stopover and as a marshalling yard.

It is still today the seat of important port structures.

Cargo ships sailed inland against the current with the towage system, i.e. hauled with cables from the shore using oxen or human operators called helciarii.

Of the different branches of the Rhône, the one of Ulmet and the Fossa Mariana were mainly used, and each arm of the river was specialised in the transport of certain commodities.

The Fossa Mariana is a canal built in 102 BC by the consul Gaius Marius. Historical sources describe it as a barrier built to hinder the invasion of the Teutons and Ambrones headed towards Italy.

Another hypothesis assumes that it was intended to facilitate inland traffic, rendered difficult by the swampiness of the area. But it seems unlikely that in a state of war one could think of civil works of this magnitude.

It is certain that later the Fossa Mariana was used for over a millennium for river transport, until it silted up and even its traces were lost. Only recently has the canal been the subject of research.

As we have said, the journeys of the goods from Fos to the internal markets were several orders of magnitude longer than those necessary for the transport from Ostia to Rome; which, we remember, was only about 20 km taking into account the meanders of the river. Consequently, the boats used along the waterways were also different.

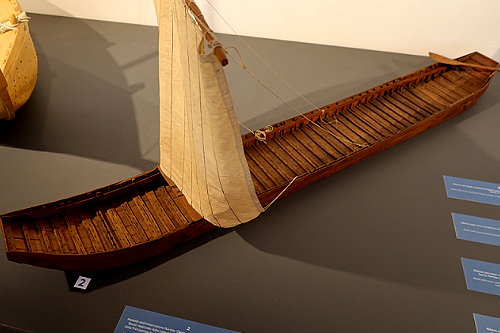

The ship museum exhibits the model of a transport ship used on the Rhine in Dutch territory.

Also in Koblenz, on the course of the Rhine in Upper Rhineland (Germany), models of the ships are on display which were used during the Roman Empire for river transport.

Also in Koblenz, on the course of the Rhine in Upper Rhineland (Germany), models of the ships are on display which were used during the Roman Empire for river transport.

As we can see, they are not different in their basic form, and could not have been, from those still used today if one disregards the construction materials, dimensions and propulsion systems.

Therefore, in those times long gone by there existed a complex network of transport by land and by water. It made goods necessary for daily life and for public works available throughout Europe, whether they were aquatic or terrestrial resources .

Thus ends this journey which, inspired by the finds and documentation of the Fiumicino Ship Museum, actually led us to "fish" very far away.

Thus ends this journey which, inspired by the finds and documentation of the Fiumicino Ship Museum, actually led us to "fish" very far away.

On the other hand, we know one thing well and are reminded of it by this funerary monument on display at the Museum of Ostia Antica: here we see the surprising results of a fishing trip with a seiner.

When you go fishing you can never know in advance if you will catch something, and what.

But we also know - we already knew but here we have further proof - that the ocean, the sea, the rivers and lakes are our friends.

We owe them due respect, and reciprocate their friendship.

Paolo Bottoni, January 2023

Unless indicated otherwise the photos are by the author