Excitement in and around the European Parliament. Droves of primarily young people standing in line to get their entry passes. They were among the 2000+ people registered for the 'Beyond Growth' Conference in the European Parliament, convened in hybrid mode. Only about half could participate in person. How can we all live dignified lives within planetary boundaries, the one planet we must share with organisms on the land, in the ocean and with fellow citizens everywhere?

Excitement in and around the European Parliament. Droves of primarily young people standing in line to get their entry passes. They were among the 2000+ people registered for the 'Beyond Growth' Conference in the European Parliament, convened in hybrid mode. Only about half could participate in person. How can we all live dignified lives within planetary boundaries, the one planet we must share with organisms on the land, in the ocean and with fellow citizens everywhere?

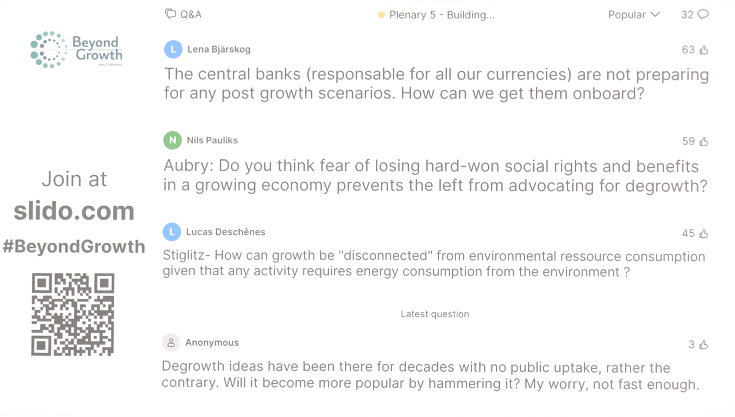

The central concern of the conference clearly captured the imagination of the fantastic line-up of scheduled speakers from politics, research, think tanks, advocacy groups, trade unions - and the participants flocking in as of 7h on a Monday morning to get a place. Key organiser Philippe Lamberts heading the Greens in the EP welcomed speakers and participants.

Contrary to the first such conference five years ago, this time, not only were more political families involved in the organisation, but also the European Commission's top representatives, including President Ursula von der Leyen. The atmosphere was electric, especially when celebrity speakers combined key facts demonstrating the need to restructure the economies with advice pointing to what could be done, particularly at policy and institutional levels.

A central point was to change the goal from 'eternal' GDP growth to social prosperity. GDP is measuring all economic activities irrespective of whether they were good or harmful for people and planet and says nothing about human welfare and the state of health of our planet. It's time to rethink of what matters was a key concern. Surely, we need to question why longivity in rich countries stops or shrinks. Conversely, people in some Greek islands with very limited infrastructure and consumerism anemities, such as in Ikaria, seem 'to forget to die'? Researcher Giorgos Kallis suggested an answer that might not work everywhere, but certainly worked in Ikaria: lots of waking, talking and festivities. Not that people on the island did not have to work hard for their living, but their low impact life styles ensured a good life, prosperity with little in a locally functioning system, not destroyed in the name of modernity. Recognise it when you look around with open eyes and mind.

Reducing resource use was also urgent to address security risks provoked by excessive dependency for critical minerals from few countries according to Olivia Lazard from Carnegie Europe. She warned that the explosive growth of the IT industries did not help to decarbonise the economy. It was, on the contrary, requiring more and more resources. She cautioned about multiple risks and advocated preventing another scamble for Africa, this time in the name of 'green growth' or a 'green economy'.

Understanding the biophysical limits to growth is essential for building an economy that respects planetary boundaries. Johan Rockström, Director of the Potsdam Climate Impact Research Institute, was unequivocal. The four overlapping crises - the climate crisis, the ecological crisis, the covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine - were already provoking high social and economic costs engendered by exceeding 6 out of 9 boundaries. In his sober manner, he reminded the audience that between 1971 and 2018, the rise in Ocean Heat Content accounts for over 90% of Earth's excess thermal energy from global heating. That brings us close to hard wired tipping points which will shift the Earth System into an entirely different gear. We are close or perhaps even beyond four of them, for example as far as the West Antarctic ice sheet and Greenland glaciers are concerned. By all means did he want to encourage decisive counter measures.

Business as usual or a quick technofix just won't do it. We have major transformations ahead and the issue is how to shape them in ways that are good for people and planet.

Blue Doughnut - Recover and protect - for a healthy ocean

What about the ocean that covers some 70% of the planet's surface and is by a long margin the biggest connect ecosystem?

The Blue Doughnut was at the centre of a session on Day 2 of the conference, organised by Seas at Risk with moderation by MEP Dino Giarusso from Sicily. Monica Verbeek, Executive Director of Seas a Risk opened the panel contributions inviting the ocean to the conversation to pay tribute to its fundamental importance to the air we breathe, the climate, food, jobs, recreation and more. Developing good understanding of the biophysical boundaries of the ocean as the outer limit of the doughnut and the human and social dimensions as the inner limitation was still in its infancy.

Kate Raworth of Oxford University and creator of the original 'doughnut' concept suggested to adapt and modify the basics as required to meet the needs of driving towards ocean recovery and health. She also suggested to use five criteria for engaging with companies in the maritime industries:

(1) purpose - in service of life?,

(2) networks - quality of relationships,

(3) governance - who has voice and which metrics are used to measure success?

(4) ownership - family, shareholders, employees, cooperative?

(5) finance - what is the expected return servicing the purpose?

Hans Bruynickx, Executive Director of the European Environment Agency (EEA), reminded participants in a soft-spoken, yet forceful manner that isolating the ocean from action towards transitions was incompataible with observed realities. Anything short of ecosystem management was inacceptable. He strongly criticised opposition to urgent ocean protection and pleaded to

Hans Bruynickx, Executive Director of the European Environment Agency (EEA), reminded participants in a soft-spoken, yet forceful manner that isolating the ocean from action towards transitions was incompataible with observed realities. Anything short of ecosystem management was inacceptable. He strongly criticised opposition to urgent ocean protection and pleaded to

- stop drilling in the ocean

- stop dumping waste into the ocean

- stop depleting renewable ocean resources

- stop 'developing' if it is having a negative impact on the tired ocean

- stop dividing and destroying the global commons.

Ingrid Kelling, Director of the Global Centre for Social Sustainability in Seafood Supply at the Heriot Watt University in Edinburgh, added explanations and a strong plea in favour of small-scale fishers, men and women, who represent 95% of the work force in the sector. Even beyond the abuses associated with illegal, unregulated and unrecorded (IUU) fishing, fishers and fish workers were at the receiving end of overfishing and poor labour standards in many places. Moreover, huge quantities of the precious resource were wasted instead of systematically using the whole fish.

We can not agree more and underline the critical importance of fish, in particular small pelagic schooling fish, such as sardines, anchovies, mackerel and horsemackerel for an equilibrated nutrition in the Global South. A study on the topic recently made waves (1).

This may not yet be common knowledge, despite recent efforts to shine a light on small-scale fisheries (2), but the elefant in the room is maritime transport. Christiaan de Beukelaer at Melbourne University is a long-time researcher monitoring the industry that is the seventh largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, at a par with Germany. Contrary to the image of the shipping industry as a 'servant of trade' de Beukelaer's investigations have convinced him that shipping maintains global inequalities. Why? Because shipping is far too cheap and with the mantra of being a 'servant of trade' has escaped even mention in the Kyoto Protocol and other global climate and sustainability agreements over the last 30.years. Yet, its emissions stack up to 1 billion tons CO2 per year. By comparison, Africa's one billion people account for 1.5 billion tons per year.

It has taken a lot of pressure until the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in London agreed to aim for zero emissions by 2050. This looks like too little too late. What could be opportunities for reductions? First, the climate neutrality IMO style looks only at the technological how. But it would be useful to start looking at the WHAT is being transported, HOW MUCH and WHERE TO. While some say, let the market decide at an annual transport volume of some 11 billion tons, it looks very much as if maritime shipping were the 'enabler of trade', not its 'servant'.

If this is so, could shipping become a co-'regulator of trade'? Some things at least are set to change. At the forthcoming July 2023 IMO meeting it is expected that discussions will tackle the inevitable increase of costs. While that is likely to have only minor effects for Europe, in the Global South that could spell greater difficulties. In this context, some Pacific countries demand a global levy from shipping at USD 100 per ton of transported goods. That would result in a global fund of about USD 100 billion per year to be used for equitable transitions to sustainable economies and be used towards loss and damage compensation.

If this is so, could shipping become a co-'regulator of trade'? Some things at least are set to change. At the forthcoming July 2023 IMO meeting it is expected that discussions will tackle the inevitable increase of costs. While that is likely to have only minor effects for Europe, in the Global South that could spell greater difficulties. In this context, some Pacific countries demand a global levy from shipping at USD 100 per ton of transported goods. That would result in a global fund of about USD 100 billion per year to be used for equitable transitions to sustainable economies and be used towards loss and damage compensation.

Will that be enough to have a down-regulating effect? This may not be enough for an industry of that size and power, but it would be a step in the right direction.

(1) Hicks, C.C., Cohen, P.J., Graham, N.A.J. et al. 2019. Harnessing global fisheries to tackle micronutrient deficiencies. Nature, 574, pages 95–98 (2019) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1592-6

(2) FAO, Duke University, WorldFish, 2023. Illuminating Hidden Harvests.The contributions of small-scale fisheries to sustainable development. Rome, FAO https://doi.org/10.4060/cc4576en

Moving forward towards sufficiency and wellbeing

The ambition of the conference was clearly to go beyond diagnosis and point towards directions for overcoming increasing inequality, the appropriation of untold wealth by the top 1% of the global population that account for the vast majority of climate gas emissions and material consumption, more than the bottom 40%. Hence 'beyond growth' is the goal. Several speakers identified the still growing inequality as a critical driver that affected all the physical, chemical and biological effects that even cushioned Europeans feel in the form of heat waves, the pandemic, water shortages not only in the Mediterranean, distress of economically vulnerable groups. How can it be deemed acceptable that more than USD 260 billion were paid out as dividends, while workers' salaries increased by only 4% in the face of often double digit inflation?

The ambition of the conference was clearly to go beyond diagnosis and point towards directions for overcoming increasing inequality, the appropriation of untold wealth by the top 1% of the global population that account for the vast majority of climate gas emissions and material consumption, more than the bottom 40%. Hence 'beyond growth' is the goal. Several speakers identified the still growing inequality as a critical driver that affected all the physical, chemical and biological effects that even cushioned Europeans feel in the form of heat waves, the pandemic, water shortages not only in the Mediterranean, distress of economically vulnerable groups. How can it be deemed acceptable that more than USD 260 billion were paid out as dividends, while workers' salaries increased by only 4% in the face of often double digit inflation?

So what about structural remedies?

Decolonising international relations in trade and international organisations was a theme illustrated by many speakers to undo deep rooted injustices not only in the Global South, but also affecting socially weak groups in Europe. As speaker after speaker highlighted aspects of how colonial regimes had curtailed the opportunities for people and companies in colonised countries and how these conditions cast large shadows into modern exchange relations upheld by international corporations and many governments. These perpetuated the injustices and cost people's lives as last seen during the covid-19 pandemic.

We also see them on the water: industrial fleets plundering waters of African and Latin American countries or mining firms now pushing hard for deep sea mining to perpetuate overexploitation of materials while already six out of nine planetary boundaries are breached. And marine life suffocating from plastic and other waste discarded into the ocean.

How come the ministers of finance of the G7 have more voting rights in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) than the ministers of finance of countries in the Global South? How come that trade rules with strong export orientation persist to direct these countries economies to satisfy the needs of Europe and other industrialised countries rather than those of their own populations? How come only 12% of products and materials get recycled at the end of their useful lives while the hunt is on for ever more aggressive mining and extraction for the insatiable appetite for energy and materials of industries.

Do we need fast fashion, more and heavier cars, rapid replacement of one electronic device after the next, the run for more exotic materials and rare earths? What we see is that every so-called efficiency gain in newer technology is overcompensated with more, even exorbitant demands on energy and material resources. Let's ask what we really need to be happy and healthy. A rate of 25% of the population with anxiety syndromes and serious mental health problems in Europe and the US is an invitation to pause and rethink how we live now and how we could envisage a better future.

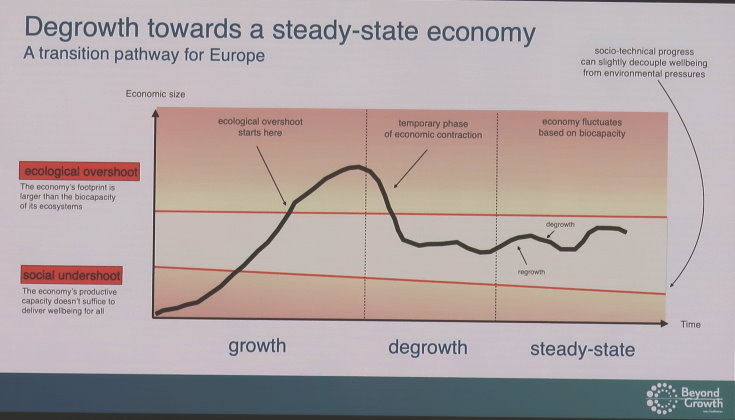

A lot of the research points to the realisation that once basic needs are met, rich social contacts and relations give us health and happiness. Then the question becomes, if we relegate the dictatorship of eternally growing GDP to the past, how can we maintain social services from pensions to health care and education? How can we reduce the useless and polluting part of overconsumption without giving up welfare and give space to economic growth in the Global South to meet basic needs for all there as well?

The estimates for the initial investment into this restructuring of the economy were in the order of 520 billion USD per year, someone even mentioned USD 900 billion. That would keep many people out of harm's way and move us back towards production and consumption patterns within planetary boundaries, especially addressing also needed growth to meet unmet basic needs in the Global South while ensuring continuity of social systems in Europe. Research suggests that much of this investment is not appetising for private profit seekers and must therefore be shouldered by public resources.

If we want to respond to the deepest human needs for health and belonging, if we want to move towards a care economy, this is a blue print for livable futures, not a side show for marginalised groups. Tim Jackson, Director for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP) at the University of Surrey, left no doubt that to win the narrative it was essential to confront the impossibility argument always pulled out to sabotage change. That required a sense of struggle for the future to muster the energy needed to overcome the staying power, the media power and fake news servicing the top 1%.

The programme is available here; the recordings of the seven plenary sessions and 20 parallel focus panels will shortly be available from the EP website. That may help counter the deafening silence in most mass media about the conference.

The talks and discussions raised the question, what to do next? Perhaps a conference can not answer that question, but it should inspire lots of roundtables and dialogue fora with as broad a participant range as possible to look what could be done in every city, region and country. Let the different experiences meet, even clash, but let people search to blend the different experiences with what the sciences are telling us to look for solutions. Wisdom of crowds can often help to find ways out when the issues at stake matter to all of us.

A number of youth groups certainly thought so and raised their hand-made posters with their demands in the closing session. It will not stop there. Organising the drive for restructuring the extractive economy and the institutions sustaining current pathways is a mammuth task requiring good planning, organisation, energy and stamina. The energetic atmosphere at the conference certainly injected some of that and will serve as inspiration for the next practical steps from local to global, across all sectors and stakeholder groups.

Text with conference impressions and pictures by Cornelia E. Nauen unless indicated otherwise.