Brussels, 23 November, 2017 - The high-level workshop in the European Parliament with well-informed speakers, including representatives from Interpol and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, was convened by Ricardo Serrão Santos, MEP and Chair of the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Working Group of the EP Intergroup on "Climate Change, Biodiversity and Sustainable Development", and Alain Cadec, MEP and Chair of the Fisheries, Aquaculture and Integrated Marine Policy Working Group.

Brussels, 23 November, 2017 - The high-level workshop in the European Parliament with well-informed speakers, including representatives from Interpol and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, was convened by Ricardo Serrão Santos, MEP and Chair of the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Working Group of the EP Intergroup on "Climate Change, Biodiversity and Sustainable Development", and Alain Cadec, MEP and Chair of the Fisheries, Aquaculture and Integrated Marine Policy Working Group.

Criminal offences in the fishing industry have many facets. Documentary fraud, tax evasion, money laundering, forced labour, human trafficking, organised crime, illegal fishing and corruption are among the most frequent and serious offences all along the value chains of the fishing industry. The way these criminal practices have developed in the last few decades transcents even broad traditional definitions of fisheries resources management and protection. Combatting them requires work well beyond the scope of sector department with strong cooperation with fiscal and tax authorities, public health agencies, the police, coast guard and other public bodies. Even in industrialised countries the rules of engagement to ensure seamless collaboration of agencies and institutions is not always well defined and capacity in place to push back widespread offences.

In developing countries, the public administrations are even less well prepared to cope. A particularly badly affected region is West Africa where almost 50% of catches are due to IUU fishing (illegal, unregulated and unregistered) which costs the countries an estimated US$2 billion worth of lost revenue per year! (1,2)

To make matters worse, the worst offenders are industrial vessels often operating across transnationally. This makes persecution particularly hard. Indeed from the presentations of Olga Kuzmianok of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and Alistair McDonnel of Interpol it became immediately clear that offenders spy out the extent to which countries have functioning management and control procedures in place and selectively commit administrative and criminal offences in those ill prepared to deal with them. Moreover, it is not uncommon to observe that the same vessel may partly operate legally under licence of an access agreement, but switch to IUU fishing opportunistically.

To make matters worse, the worst offenders are industrial vessels often operating across transnationally. This makes persecution particularly hard. Indeed from the presentations of Olga Kuzmianok of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and Alistair McDonnel of Interpol it became immediately clear that offenders spy out the extent to which countries have functioning management and control procedures in place and selectively commit administrative and criminal offences in those ill prepared to deal with them. Moreover, it is not uncommon to observe that the same vessel may partly operate legally under licence of an access agreement, but switch to IUU fishing opportunistically.

Olga Kuzmianok gave the most detailed description for the most frequently encountered types of offence at each stage of the fisheries value chain, from preparation through fishing to conditioning, processing, transporting and sale. Fraud, forgery and corruption were observable at every step. There was a significant area of overlap between IUU fishing or directly fisheries related crimes and transnational organised crime.

From experience, she noted that the traditional compliance approach in fisheries was insufficient to address the related offences. IUU fishing can no longer be considered in isolation from other criminal practices along the fisheries value chain. She underlined the need to consider the links between illegal fishing and organised crimes along these value chains. Her office had observed that often times it was easier to tackle the transgressions from the side of economic crime as the public administrations addressing this type of crime were often more alert to the issues, while the fisheries sector legislation in a number of countries did not even recognise illegal fishing as criminal offence.

Fisheries crime in its various manifestations is essentially an economic crime which is either perpetrated to increase the profits of outwardly legitimate businesses or to facilitate organised crime. The fisheries part comes usually in two variants: obtain the right to illegitimate catch or to fraudulent product sale (quantity, quality, species). The organised crime part also has two major modes: crimes aimed at harvesting high value stocks and crimes using fisheries as a front for human and drug trafficking etc.

As for compliance strategies, she distinguished four tiers for the attitudes of economics agents and the most effective response of public authorities. The first tier agents were willing to do the right thing and its was important to make it easy for them to comply. The second tier tried to comply, but did not always succeed. Support towards compliance was the most appropriate answer in this case. The third tier was not intent on compliance but would, if faced with strong monitoring, control and surveillance. This was, infact, the right response towards these agents. Only the last tier put considerable criminal energy into non-compliance and then needed to be pursued with the full force of law enforcement.

The percentage of successful crime persecution is low, though a number of highly visible cases demonstrate it can be done. Developing and feeding crime databases through targeted research and offering capacity building around their use is among the first recommendations to increase success rates. Strengthen national and international networks of agencies responsible for different aspects of crime is another important part of the equation. Click here for the presentation.

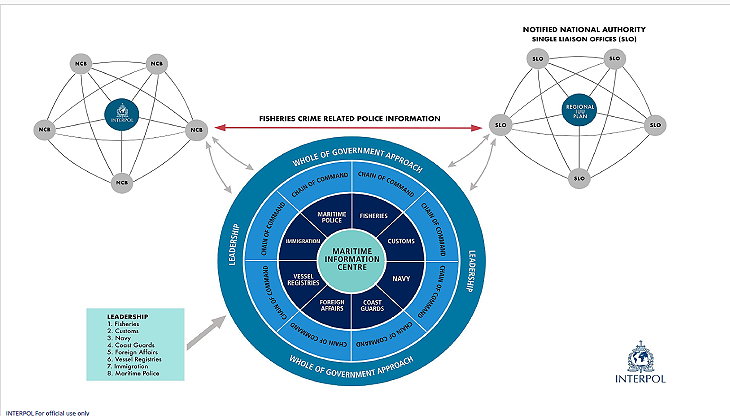

Alistair McDonnell of the Environment Security Unit of Interpol elaborated on practical experience on how easy it was for investigators to be mislead towards minor offences while big tax evasion, fraud or worse was going on "behind their backs". He went into some length to explain the difficulties to sharpen awareness in the many administrations and agencies responsible for different aspects of organised crime and the need for broad-based cooperation. Interpol was supporting capacity building in setting up clear rules of engagement to make such cooperation happen. They had a particular role when it comes to even more demanding collaboration when seeking to repress transnational crime. Click here for the slides.

Several other speakers from international organisations and national fisheries administrations shared their experiences and some case histories. The invited civil society contribution of Steve Trent from the Environmental Justice Foundation focused on human trafficking and other illegal practices. He underscored the argument for counter measures with a short video that illustrated some of the horrible ground realities. The key demands for remedial action were

- mandatory vessel monitoring systems

- publicly available vessel licence lists

- mandatory use of digital log books, crew manifests and catch, landing and licence certificates made publicly available

- a global record of fishing vessels based on unique vessel identifiers (UVIs), wherever possibly using IMO numbers.

Mundus maris has produced a poster summarising key issues, which was first presented at this year's EGU Conference in April. We are also among the supporters of the appeal to the insurance industry to act up and stop insuring known IUU vessels coordinated by OCEANA. This is starting to get a response from some insurers and agents. It is clear that it is important to change the public understanding of what's going on in the criminal part of the fishing industry. The work of the public authorities towards reigning in the criminals will be helped a lot, if civil society organisations support research into the practices, strengthen advocacy against these serious crimes and ifa honest companies actively engage in avoiding transactions with the criminals.

For more information about the event in the European Parliament click here.

(1) Belhabib D, Sumaila UR, Lam VWY, Zeller D, Le Billon P, Abou Kane E, et al. (2015). Euros vs. Yuan: Comparing European and Chinese Fishing Access in West Africa. PLoS ONE 10(3): e0118351. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118351

(2) Doumbouya A, Camara OT, Mamie J, Intchama JF, Jarra A, Ceesay S, Guèye A, Ndiaye D, Beibou E, Padilla A and Belhabib D (2017). Assessing the Effectiveness of Monitoring, Control and Surveillance of Illegal Fishing: The Case of West Africa. Frontiers in Marine Science, Vol. 4, Art. 50:10 p. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00050