Venue: Henri Janne meeting room 15th floor, Sociology Institute, ULB Solbosch Campus, Ave Jeanne 44, 1050 Brussels.

Date and time: 11 March 2013, 10h to 16h.

Background:

Education is always about the future. “Global education” is a relatively new concept still in mutation, which examines what should be contents and modes of teaching to prepare young people in different parts of the planet for living peacefully and in synch with themselves, with each other and with nature.

A key challenge is how to develop contents and processes that enable young people to build up the competence and skills to live well and perform in their local environments, while being aware and capable of putting the local requirements and opportunities into broader, global perspectives.

Competences in the sciences and technical subjects should certainly receive much attention. Likewise, social skills, respect for difference (in culture, language, gender, religion and other dimensions of multiple identities) and the ability to cooperate with global peers should be considered essential part of the education process.

Last, but not least, being curious about and respectful of nature, land and ocean ecosystems and reconnecting to nature in multiple ways needs to be part and parcel of a future-oriented approach to accompanying young people on the journey into their adult lives.

Rebuilding relationships with nature that produces the objects that surround our daily lives may also help to stem the waste and encourage longer-lived use of construction, furniture, dress and reduce food wastage.

The workshop intends to cast light on at least some major aspects of education for sustainable futures bringing together academic research, practitioners interspersed with perspectives from traditional culture in the form of a video-interview with a leader of the Senegalese women in artisanal fisheries, Awa Seye.

Workshop participation, including the video-projection during lunch break, is open, but registration at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. encouraged. Awa Seye will be present for an exchange of experience.

The workshop will be convened in English and French without simultaneous interpretation, however, consecutive translation can be provided if required. Panelists and participants are free to use either language to express themselves.

Click here to see the programme.

Highlights from the workshop - the opening

by Prof. Stella Williams

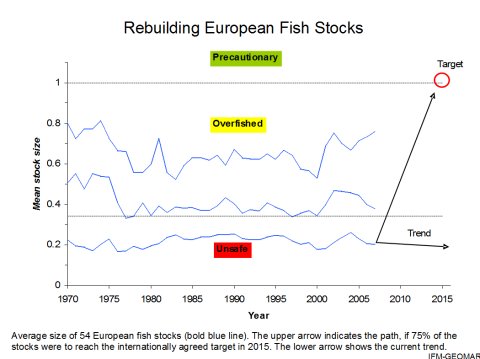

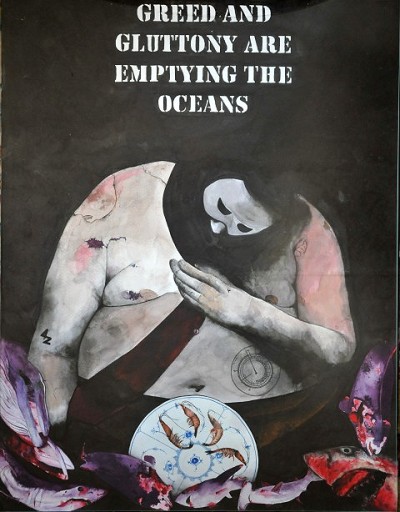

Cornelia E Nauen, President of Mundus maris, welcomed the participants and opened the workshop in the pleasant premises of the Institute of Sociology at the ULB. Setting the scene for the discussion, she recalled that Mundus maris at its core was mobilising the sciences and arts in a creative tension to enable a better appreciation of the world around us. Science tells us a lot about how far humanity has overshot the budget of what nature can produce and regenerate in a year. Last year, ecological overshoot day was 22 August.

That means the resources we consumed during the remainder of 2012 were borrowed from 2013. The land and the sea which enable our civilisation to exist are overexploited in many parts of the globe with production and consumption patterns unsustainable.

As Charles Hopkins, UNESCO Chair for “Reorienting Teacher Education to Address Sustainability”, York University, Toronto, Canada, had noted in an earlier workshop at the EADI Conference in 2011, that education concepts in many industrialised countries were not leading us into the transition towards living in peace with one another and our planet. The overconsumption in these countries gave many children and youth a distorted picture. Education in so-called developing countries, which were more economical in their use of resources but had other shortcomings, could provide valuable learning ground while at the same time benefiting from more exchange with school systems elsewhere.

In an interdependent world heading towards an unpredictable climate regime of well above 2 oC new thinking and new approaches to eduation were required to cope with the unknown ahead. How to help prepare the next generations to accommodate an additional 2 billion of humans on the planet, while providing suitable living conditions for all, humans and other organisms? How to manage the restoration of degraded land and marine ecosystems to do that? How to do that by reducing energy consumption by 80% so that the climate system would not go entirely out of kilter? How to develop the technical knowledge and the all-important social skills required to achieve these major societal changes in a non-violent manner? The present workshop was intended to create a conversation space for people approaching the issues from very different angles as a contribution to this huge challenge. From the perspective of Mundus maris, it was expected to come out with robust orientations as to where efforts on eduation for sustainability would be most effectively focused so has to support change in that direction.

Paul Jacobs of SEDIF, organiser of Campus Plein Sud at the ULB, walked the participants through a review of concepts on development that had guided research and activism

since the late 1950s. With decolonisation came the notion of development, but based on industrial production and other imported models, which quickly turned out to be inadequate, if not deleterious to the former colonies.

The 1972 report of the Club of Rome "The Limits of Growth" made lots of waves, not the least by calling into question the development model of the industrial countries and its effects on global resources and developing countries. Fifteen years later, the Brundtland Report "Our Common Future" of 1987 paved the way for the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 which gave rise to the Convention on Biological Diversity, until recently the international treaty most countries in the world had ratified or adhered to.

After the end of the bipolar world in the 1990s, there was also a stronger movement to seek cooperation with developing countries rather than for them. The development community was also questioning itself and the models underlying the development discourse and practice. Approaches to the global and regional trade regimes and the increasingly global reach of transnationally operating companies continued raising new challenges on how to pursue objectives of social justice, rights to dignified lives and protection of the natural environment on which particularly economically poor people depend overproportionately.

In the new century, the political and economic stage is becoming increasingly multipolar and interdependent, thus forcing new reflections as to what development and more specifically sustainable development might mean and how international cooperation and solidarity can help to address the negative sides of globalisation more effectively. More than enough food for critical thought for this and other workshops to come.

With this and following a short self-presentation of participants, Stella Williams as moderator gave the floor to Tobias Troll, the Project Manager of the new DEEEP Project. He echoed some of the historical perspectives of Paul Jacobs by emphasising how some uncritically used concepts such as poverty, typically used from a 'Northern' perspective, had at times had perverse effects on development studies and practice. In particular, it had reduced for some time the perspective on financial means, paying little attention to culture, citizenship and other resources of societies.

He challenged traditional development approaches based on ideas of a "powerful giver - grateful receiver". Likewise, the first six Millennium Development Goals remain a technocratic response to a global crisis, accepting moreover that not all humanity, but some percentage of this or that subgroup had the rights to essential services, such as education, health care and clean water and basic sanitation. While these were laudable goals, they did invite the question of who would decide on who was in or out. Moreover, they were by themselves not achievable without MDG 7 "environmental sustainability" and MDG 8 "A global partnership".

He referred to the work of CONCORD, the apex organisation representing some 1800 non-governmental organisations in national platforms and networks in 27 European Union Member States. The CONCORD DARE Forum operates the development education and awareness raising working group of the confederation. It focused on the need for a global civil society and for citizens to engage with development to achieve the legitimacy required for broad-based consensus and steering change. Public engagement is considered essential to open a deliberative space, to enable dialogue, mutual learning, participation and purposeful interaction of citizens.

The enrichment of currently accepted paradigms to underpin international cooperation in the future consists of the following reformulation:

- Citizen's empowerment for change is a central principle of a Human Rights Based Approach to development

- Policy Coherence for Development can only be effective if supported by public mobilisation

- The public needs to critically assess aid and development and thus contribute to the principle of development effectiveness.

CONCORD, is promoting these principles and has been working on global education for some time. The new DEEEP project, just started in earnest a few days ago, will instill new impetus into these debates and work for citizens' empowerment for global justice. It will build on the previous work on education, awareness and efforts to eradicate poverty. It will require a lot of critical reflection, new thinking and practice to open spaces for global education and citizenship around the world.

Maria del Carmen Patricia Morales from the University of Leuven spoke about “Rethinking sustainability from the perspective of an ethics of solidarity and diversity”. Her starting point was the paradigm shift brought about by the Brundtland Commission and the Club of Rome. These pathbreaking collaborations shifted the dominant egocentric concepts into an ecological direction, where humans are not the centre of the universe, but part of the life support system Earth.

Maria del Carmen Patricia Morales from the University of Leuven spoke about “Rethinking sustainability from the perspective of an ethics of solidarity and diversity”. Her starting point was the paradigm shift brought about by the Brundtland Commission and the Club of Rome. These pathbreaking collaborations shifted the dominant egocentric concepts into an ecological direction, where humans are not the centre of the universe, but part of the life support system Earth.

Integrating ethics into these ecological perspectives leads to a different view of categories “we” and “others”. Expanding that view into the future should help overcome the current boundaries of the human condition and lead to more responsible behaviour. Being aware of the rights of the other is not only a way to discover “the other”, but also to discover ourselves. “The other” does not only include the whole of humanity, but also nature.

We have made quite some progress to give ethics greater room. That war is considered a bad thing is new. It was not so in most of human history. Slavery is now banished almost everywhere. One could cite other advances of civilisations. However, much of our practice is not coherent with these advances and falls short of the accepted principles. What catalisers can we think about to accelerate transitions to systematic adoption of ethics and sustainability?

We can thus be moderately optimistic, however, welfare is not universal and that's a big problem.

Kari Kivinen from Finland is the Secretary General of the European Schools and a committed teacher paying as much attention to the academic achievements of the pupils as to their social skills and civic engagement. In this role he is interested to ensure that useful pedagogical initiatives benefit all pupils, not only a small group. Looking back at the last decades in the education system, Kari Kivinen noted that education focused on facts the 1980s, was mostly normative-based in the 1990s and has become more pluralistic in the new century.

Kari Kivinen from Finland is the Secretary General of the European Schools and a committed teacher paying as much attention to the academic achievements of the pupils as to their social skills and civic engagement. In this role he is interested to ensure that useful pedagogical initiatives benefit all pupils, not only a small group. Looking back at the last decades in the education system, Kari Kivinen noted that education focused on facts the 1980s, was mostly normative-based in the 1990s and has become more pluralistic in the new century.

Education for sustainable development (ESD) has evolved out of environmental teaching. ESD allows every human being to acquire the knowledge, skills, attitudes and volues necessary to shape sustainable futures. Objectives today are the empowerment of the pupils, so as to increase their readiness to take their own decisions; the competence to act and the encouragement of entrepreneurial spirit. ESD requires participatory teaching and learning methods that motivate and empower learners to change their behaviour and take action in favour of sustainable development. Core competences promoted are critical thinking, imagining future scenarios and collaborative decision making.

There is a good crop of international and European policy documents supporting ESD. Recent examples are the Bonn Declaration, UNESCO, March 2009, the 2009 Review of the EU Strategy for Sustainable Development, and even more recently the Rio+20 Conference, UN, June 2012. No matter how good the declarations and strategies are, it remains a challenge to translate their principles and orientations into the syllabus and the daily efforts in the European Schools.

We are concerned not only that the pupils learn about the principles of sustainable living, but that they do what they have learnt: Working for the public good based on critical thinking they should learn at school.

As teachers working with young people, we are constantly asking ourselves, how to make this happen. We need to provide them with the tools to understand and take care of the world in which we live in and which they will shape in the future.

As recently as February 2013, a decision was taken to create a working group composed of teachers, students and school inspectors on how to establish that type of sustainability practice in school. It has already started to analyse the syllabus and the good principles from early education. But the members are also asking themselves whether this is enough.

The European school teachers want to protect the bottom line, respect nature and “others”. Kids love nature as a default position and the school should protect and consolidate that positive attitude.

What seems to work? What is important is that everybody can participate, not only a priviledged few:

-

e.g. recycling works for all ages, but it works only, if all adults do it too!

-

theme weeks seem to work well;

-

lighthouse projects such as the twinning Mundus maris enabled between an arts class of the European School in Uccle, Belgium, and the CEM in Kayar, Senegal, is valuable, but should be taken to a larger scale, through the exhibition of works from both teams enabled to share the proceeds and experience more widely;

-

rice day to for fund raising for social projects;

-

debates that help hone critical thinking and developing consistent arguments;

-

children-to-children activities;

-

all kinds of activities helping to green the school and daily lives ... from solar panels on the roofs, saving materials etc., but in addition, it is important to promote activities for practicing solidarity concretely.

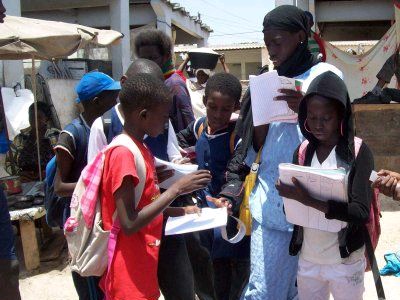

The moderator introduced Aliou Sall, a Senegalese socio-anthropologist with more than two decades of experience in the fisheries of the country and West Africa. He coordinated testing teaching aids for introducing an ecosystem approach to fisheries in 10 schools in Senegal and Gambia. The development and testing of the teaching kits was work carried out for the FAO's EAF Nansen Project and followed up by Mundus maris.

These pilots were carried out in collaboration with schools in fishing communities, which were very much embedded in their local context. They started with a needs assessment of the schools in relation to communication means already in use and others which were considered desirable. As a result, the development of the teaching aids then sought to make available scientific knowledge in teaching formats, which incorporated traditional culture, such as theatre, with class-based and excursion-based exercises. The content focused on five interdependent principles. They are:

These pilots were carried out in collaboration with schools in fishing communities, which were very much embedded in their local context. They started with a needs assessment of the schools in relation to communication means already in use and others which were considered desirable. As a result, the development of the teaching aids then sought to make available scientific knowledge in teaching formats, which incorporated traditional culture, such as theatre, with class-based and excursion-based exercises. The content focused on five interdependent principles. They are:

-

maintaining ecosystem integrity (no fish is an island);

-

promoting precautionary approach to fisheries and other use of marine and coastal ecosystems and respecting the rules;

-

ensuring broad stakeholder participation;

-

promoting sectoral integration and safeguarding livelihoods;

-

investing in research and knowledge.

Drama and role plays turned out as perhaps the most important tools to address conflict between different practices and perspectives met during the exercises as well as for appropriating new content.

Mundus maris is also exploring other ways to build bridges between still lively traditions and modern knowledge in ways that are intended to give access to the best of both to the young people. There are e.g. challenges on how to rescue ethnoscientific knowledge by valuing it (again). One way of sharing such values used is to invite old fishermen and other experienced individuals in the traditional communities to share their insights and orientations through modern media, such as video. There is good reason to explore such routes as quite a number of formerly emblematic species have all but disappeared as a result of overfishing.

The results so far are quite encouraging. In Gambia there are on-going attempts to institionalise various efforts to update the syllabus. In Senegal the teachers have also continued with extra-work but the engagement with the education department and its school inspectors is still in its infancy. The schools are quite interested in international cooperation as a way to upgrade their teaching conditions and offer better opportunities to the kids. Perhaps there could be a meeting of minds and action between the ambitions of the European Schools and those in West Africa.

For the remainder of the morning Stella Williams moderated the debate centered on the panel's remarks. Interrupted by a sandwich lunch and the projection of the video-interview with Awa SEYE, the leader of the Senegalese women in artisanal fisheries, all of the afternoon was spent discussing what could be practical implications for several on-going and planned projects. The video actually represented another type of input to the reflections, namely how to find a new equilibrium between tradition and modernity as applied to school education and, for that matter, on life-long learning.

Two of the more interesting aspects of the follow-up to the pilots under FAO's EAF Nansen Project were first that the kids discovered through the use of fish rulers, a quantitative notion not so dominant in the traditional oral culture, that they could enter into a useful dialogue with adults. Infact, their discovery that fishing babyfish was quite common and an indication of unsustainable practices, led to many debates not only in school, but also in the community.

The second was a convergent interest of fish mongers in several markets to get fish rulers and to familiarise with their use in response to fearing their business had no future if overfishing continued unabated.

Bringing teaching aids and practical exercises in real life situations to the schools the sense of relevance of the teaching was sharply increased. This was particularly the case as the exercises touched on a very real sustainability issue.

Margareth Hammer commented on the weakening links between the generations and how this leads to loss of knowledge, not only traditional knowledge. From her own decades-long work in many countries, she argued in favour of renewed links between people of all age groups to ensure what she termed "transgenerational knowledge", or the transmission of knowledge within the family and community between the elders and the youth. This could be among the feasible responses to problems identified by Awa Seye in the video-interview and others during the exchange.

Other valuable comments developed the need to replace linear thinking by sustainability paradigms and why teacher training needed to be specific to different age groups, but also that teachers themselves needed updates to take onboard new methods and insights that could help them remain good stewards for the young generations throughout their often long professional careers. Peer-to-peer learning and using modern information technologies as an addition to well-established methods and teaching aids could make teaching more dynamic and effective.

Some very useful suggestions from the group in relation to on-going work in Senegal, Gambia, Nigeria and Belgium will be put into practice soon.

The workshop closed with a check-out that highlighted the hope and expectation of the participants for translating the results of the day operationally and strengthen cooperation. Reason enough to thank all those generously contributing information, documentation, life-experience and questions, whether they could be in the room or had helped in the preparations.

The voice of research: Selected links to scholars, institutions and publications

Austria:

University of Klagenfurt, Institute of Instructional and School Development. Fields of research : education networks, education development, Science Education, Life-long learning, school development. One of the researchers is Franz Rauch, Director of the Institute (in 2018)

Belgium:

Free University of Brussels - Université libre de Bruxelles, Centre de Recherche en Sciences de l’Éducation, Director: Prof. Sabine Kahn does research on education systems, learning and handling diversity mostly in class situations (from school to university), including international cooperation.

Institut d'Ecopédagogie, Liège, Belgium - President of the Board (Conseil d'administration) Christine Partoune

University of Ghent, Department of Educational Studies

Denmark:

University of Aarhus, Danish School of Education. Jeppe Læssøe, Prof. with special responsibilities and working on sustainability. See bibliography.

Finland:

University of Helsinki, Department of Applied Sciences and Education, Mauri Åhlberg, prof. for biology and sustainability education - publications

France:

Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Researcher at UMR 208 : MNHN/IRD Patrimoines Locaux, Prof. Girault Yves

Fortin-Debart C., Girault Y. (2009). De l’analyse des pratiques de participation citoyenne à des propositions pour une Éducation à l’environnement, in Éducation Relative à l’Environnement : Regards, Recherches, Réflexions. Vol. 8.

Fortin-Debart C., Girault Y. (2006/2007). Pour une approche coopérative de l’environnement à l’école primaire. Recherche exploratoire auprès d’enseignants du primaire, in Education Relative à l’Environnement : Regards, Recherches, Réflexions. Vol.6 Education à l’environnement et institutions scolaires, pp 97-117.

Girault Y., Lange J-M., Fortin-Debart C., Delalande Simonneaux L., Lebeaume J. (2006/2007). La formation des enseignants dans le cadre de l’éducation à l’environnement pour un développement durable : problèmes didactiques, in Education Relative à l’Environnement : Regards, Recherches, Réflexions. Vol.6 Education à l’environnement et institutions scolaires, pp 119-136.

Germany:

Leuphana University Lüneburg, Institute for Environmental and Sustainability Communication, Research in Education and Communication for Sustainable Development (ECSD), Prof. Gerd Michelsen, Unesco Chair - see publications

University of Bremen, Fachbereich 12, Prof. Brunhilde Marquardt-Mau used to work on pedagogical concepts for teaching natural sciences and more

Ireland:

St. Patrick's College, Drumcondra and County Dublin Vocational Education Committee did a study for Irish Aid on the image of development education.

Audrey Bryan and Meliosa Bracken, 2012. Learning to read the world. Teaching and learning about global citizenship and international development in post-primary school. Research Briefing. Irish Development Aid. 8 p. Click here for download.

Italy:

Università degli Studi di Parma, Centro Italiano di Ricerca ed Educazione Ambientale with its publications. Dr Antonella Bachiorri works and publishes specifically about education for sustainability.

The political consensus in the European Union in 2010

The European Council Conclusions on education for sustainable development of 19 November 2010 can be downloaded here.