Mundus maris- Sciences and Arts for Sustainability asbl has stepped up participation in the 2012 agenda of Campus Plein Sud at the Free University of Brussels (ULB). This time, we organised or participated in four successful events.

Mundus maris- Sciences and Arts for Sustainability asbl has stepped up participation in the 2012 agenda of Campus Plein Sud at the Free University of Brussels (ULB). This time, we organised or participated in four successful events.

The theme in the tenth year of existence focuses again on water and sustainability issues, this time with particular attention to climate change. From its beginning, the ambition of Campus Plein Sud was to inform the campus community of the many facets of development "in the global South" so as to replace the caricature of misery or exoticism often painted by the media with more nuanced understanding. The climate change and global trade and sustainability perspectives forcefully illustrates global interdependencies. The calendar of our contributions comprises:

- 29 February 2012 - NGO Forum on Avenue Paul Heger, Campus Solbosch, from 10 to 16h30

- 2-3 March 2012 - "Learning, teaching and practising - together - sustainable development", international workshop, 44 ave. Jeanne, Salle Janne, Friday from 9 to 17h45 and Saturday from 9 to 14h

- 5 March 2012 - Cine-debate "Kayar - l'enfance prise aux filets" - Forum H, Campus de la Pleine in the course of Prof. Lancelot, with Aliou Sall and Cornelia E Nauen as discussants; starts at 10h. Click here to see the poster announcement.

- 7 March 2012 - Open course "Can science save the seas?" - K1.105, Campus Solbosch in the course of Prof. Jacobs with Cornelia E Nauen as lecturer; from 16 to 18h. Click here to see the poster announcement.

Campus Plein Sud at the ULB is organised by SEDIF.

Read on for brief accounts about the activities supported by Mundus maris. For more extensive information about the international workshop 'Learning, teaching and practising - together - sustainable development', click on the link above.

NGO Forum, 29 February at the ULB

It was quite cold in Brussels on 29 February 2012. But that was no deterrent for the numerous NGOs, initiatives and associations, among them Mundus maris, to set up shop. The water crisis and food security challenges, climate change, social injustice, fair trade and access to knowledge and decent living conditions were at the centre of many stands and activities that day in response to this year's thematic orientation of Campus Plein Sud.

It was quite cold in Brussels on 29 February 2012. But that was no deterrent for the numerous NGOs, initiatives and associations, among them Mundus maris, to set up shop. The water crisis and food security challenges, climate change, social injustice, fair trade and access to knowledge and decent living conditions were at the centre of many stands and activities that day in response to this year's thematic orientation of Campus Plein Sud.

Mundus maris obviously focused on the connection between the resources crisis and the increasing vulnerability of many coastal communities directly depending on healthy and productive seas, but formost on what could be done to rebuild healthy marine ecosystems and to open up opportunities for young people through education focused on sustainable production and consumption.

The organisers of Campus Plein Sud 2012 at the Free University in Brussels (ULB) had opted this time for outdoor stands to attract more students and staff to the offer for information and discussion. From 10 to 16h30 o'clock Avenue Paul Heger on the Solbosch Campus of the ULB was transformed into a street happening with engaged discussions, hot tea and lots of leaflets changing hands.

Sharing a tent with an initiative promoting vaccination of livestock in Africa to support cattle herder in their daily struggle, the Mundus maris stand became a meeting point for interviews on the fisheries crisis and for exploring with an association of teachers how to develop stronger mechanisms to support fellow teachers in West Africa in their efforts to introduce more environment education.

Sharing a tent with an initiative promoting vaccination of livestock in Africa to support cattle herder in their daily struggle, the Mundus maris stand became a meeting point for interviews on the fisheries crisis and for exploring with an association of teachers how to develop stronger mechanisms to support fellow teachers in West Africa in their efforts to introduce more environment education.

Sandwiches from the organisers and hot tea allowed the three participants from Mundus maris, Christiane Daem, Cornelia E Nauen and volunteer Cleo Kun Zhang, to brave the cold more readily, together with many others from the NGO community.

5 March 2012 - Cine-debate "Kayar - l'enfance prise aux filets"

Forum H, Campus de la Pleine

in the course of Prof. Lancelot, with Aliou Sall and Cornelia E Nauen as discussants (photos P. Bottoni).

Prof. Christiane Lancelot (in the photo to the right) is a marine ecologist and modeller at the ULB with many years of research and high-level publications with the leading scientists in the field under her belt. She invited Mundus maris to her course of MSc bio-engineer students to present and discuss the film. She introduced the general purpose and context of the cine-debate as part of Campus Plein Sud 2012.

Prof. Christiane Lancelot (in the photo to the right) is a marine ecologist and modeller at the ULB with many years of research and high-level publications with the leading scientists in the field under her belt. She invited Mundus maris to her course of MSc bio-engineer students to present and discuss the film. She introduced the general purpose and context of the cine-debate as part of Campus Plein Sud 2012.

Aliou Sall and Cornelia E Nauen introduced the specific context of progressive resource degradation in the once rich fishing grounds in Kayar, in Senegal, and the devastating effect this had on the social and economic situation of the fishing community there.

The wider trends, of which the individual case was one example, had already been quantitatively and qualitatively described and analysed in the International Symposium "Marine Fisheries, Ecosystems and Societies in West Africa - Half a Century of Change", convened in Dakar, Senegal, from 24 to 28 June 2002, just months before the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa.

The wider trends, of which the individual case was one example, had already been quantitatively and qualitatively described and analysed in the International Symposium "Marine Fisheries, Ecosystems and Societies in West Africa - Half a Century of Change", convened in Dakar, Senegal, from 24 to 28 June 2002, just months before the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa.

A film has, of course, an entirely different quality to it. You see old and new situations with different eyes as the images create other associations and emotions in the viewer than a scientific or even a journalistic report about rigorous research will.

The film illustrates in close-up images the daily life of a boy taken out of the school to take the place of his elder brother in the pirogue, who emigrated to Spain, when overfishing made it more difficult to make ends meet.

The film also touches on several other effects on the economic decline in the lives of villagers in Kayar arising from overfishing and the difficulties to respond to changing circumstances.

A review of the film, an interview with the film maker, Thomas Grand, and the first minutes of the film itself, can be seen on this website in the section on film reviews. Click here to see.

A review of the film, an interview with the film maker, Thomas Grand, and the first minutes of the film itself, can be seen on this website in the section on film reviews. Click here to see.

Following the projection of the film, the ensuing debate focused very much on what could be done to address the key problems highlighted.

Among these, improving schooling conditions, child care, health care and viable alternatives to fishing in order to enable sustainable fisheries in the future.

The African participants of the workshop "Learning, teaching and practising sustainable development", which had taken place 2-3 March as another part of the Campus Plein Sud programme, had also come along to the film screening and the discussion with the students.

The animated discussion showed a good understanding of the students of the points raised in the film and by the discussants. It also brought to light the difficulties to find widely accepted ways to act taking into account sometimes conflicting interests. By way of example supporting the schools depends, not only on the initiative of the school teachers, the parent committee and supporters such as Mundus maris, but also on the ordinary and investment programmes of the ministry of education and its district representatives, the municipality, the credibility of the municipality's development plan and the resources that could be mobilised by various parties to implement any agreed priorities.

The animated discussion showed a good understanding of the students of the points raised in the film and by the discussants. It also brought to light the difficulties to find widely accepted ways to act taking into account sometimes conflicting interests. By way of example supporting the schools depends, not only on the initiative of the school teachers, the parent committee and supporters such as Mundus maris, but also on the ordinary and investment programmes of the ministry of education and its district representatives, the municipality, the credibility of the municipality's development plan and the resources that could be mobilised by various parties to implement any agreed priorities.

The session was concluded with an invitation to the students to combine their thematic studies with civil engagement so as to be able to work in interdisciplinary teams that can help bring about robust solutions to the sort of intricate and multi-faceted challenges visited in the film.

7 March 2012 - Open course "Can science save the seas?"

K1.105, Campus Solbosch

K1.105, Campus Solbosch

in the course of Prof. Jacobs with Cornelia E Nauen as lecturer; from 16 to 18h.

Prof. Paul Jacobs has an introductory course on the sciences for a mixed group of beginners in the natural and social sciences as a foundation course. He had invited a talk about the increasing challenges to the integrity of marine ecosystems and what this means to our societies, based on latest research results.

Despite pouring rain, a fair number of students had come to join the presentation and discussion.

The talk started with an introduction on the context of international cooperation to protect the seas interfacing science and society, arts and education and then went on to address the following sections:

- Why do we talk about a global fisheries crisis?

- Why does it matter?

- Seeking to explain human behaviour

- Some more ‘unconventional drivers’ of unsustainable fisheries

- What we can do together …

- So, can science save the seas?

Emblematic for the global fisheries crisis is the dramatic decline of large predatory fish in the North Atlantic that took place over the last one hundred years and longer. This led to significant changes in the composition and functioning of marine ecosystems.

Unfortunately, these losses in the productivity and resilience of ecosystems is not confined to the North Atlantic, where fishing has developed strongly and has early on attracted scientific interest. Scientists from many different disciplines meeting for the International Symposium "Marine Fisheries, Ecosystems and Societies in West Africa - Half a Century of Change" in Dakar, Senegal, from 24 to 28 June 2002, just months before the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa, showed similar declines in even shorter periods in West Africa.

Unfortunately, these losses in the productivity and resilience of ecosystems is not confined to the North Atlantic, where fishing has developed strongly and has early on attracted scientific interest. Scientists from many different disciplines meeting for the International Symposium "Marine Fisheries, Ecosystems and Societies in West Africa - Half a Century of Change" in Dakar, Senegal, from 24 to 28 June 2002, just months before the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa, showed similar declines in even shorter periods in West Africa.

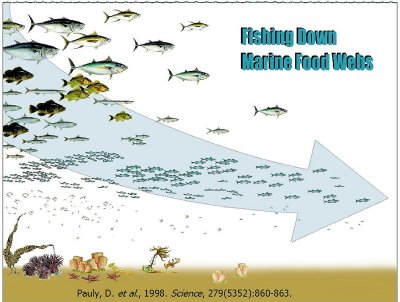

Why should we be concerned, even if we are not living directly on the coast or are eating fish on a regular basis? Well, we should, because at current trends the fisheries we know and the species we now like to have on our plates even occasionally may be gone by about 2050, within the lifetime of most of the students in the lecture hall. It happens throughout the oceans and is called "fishing down marine food webs".

Not only that, we are also seeing destruction of valuable habitat for many bottom living species through large-scale bottom trawling and other destructive production methods.

This in turn creates habitat for the polyps of jellyfish and other creatures, which are less desirable from a human consumption perspective, but also reflect structural changes in the way marine systems function after many other species have lost their living space.

Rampant overfishing is now the norm - too many boats chasing too few fish. Some economists have estimated that a large chunk of the world's fishing fleets are not only superfluous, but an active drain on their economies. Up to 50%, depending on the country, may only be 'viable' because of subsidies to their operation. In other words, they are loss-makers in times, when many people find it increasingly difficult to make ends meet.

Rampant overfishing is now the norm - too many boats chasing too few fish. Some economists have estimated that a large chunk of the world's fishing fleets are not only superfluous, but an active drain on their economies. Up to 50%, depending on the country, may only be 'viable' because of subsidies to their operation. In other words, they are loss-makers in times, when many people find it increasingly difficult to make ends meet.

Add marine litter, wide-spread illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing, bycatch, discards and other threats to that and you have an explosive mix, which should not leave anybody indifferent who would like to enjoy the beauty, food and ecosystem services of the sea also in the future.

What drives such folly? Conventional economics suggests that it's all about allocation of scarce resources and that it's better to have a little less now than wait a few years to get more. That's called the discount rate (a sort of negative interest). In uncertain times, one might operate with high discount rates and only accept to invest over longer periods in exchange for very high interest. That may be true for some investment strategies, but it has also been demonstrated that people do e.g. invest in their children and family, even if they don't get immediate or even guaranteed long-term financial and economic returns. When it comes to the regenerative capacity of nature, it does not take a biology PhD to understand that while it can be amazing, it can not match speculative Ponzi schemes (which, incidentally, also come crashing down with the next financial bubble).

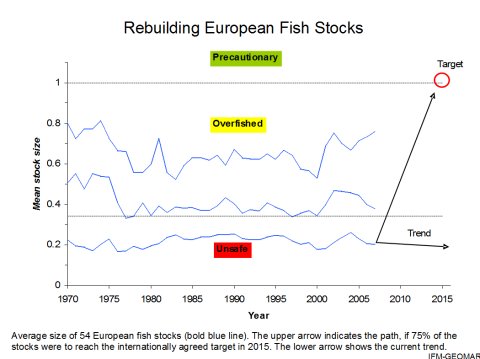

So, there is a point here of exercising a bit more precaution and resist the miraculous promises for cool headed study and assessment: it's even been done already: in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development Heads of State and Government solemnly decided to establish networks of marine protected areas by 2012 and to rebuild degraded marine ecosystems by 2015 so that they can produce maximum sustainable yield and be net contributors to the economy and to society at large.

So, there is a point here of exercising a bit more precaution and resist the miraculous promises for cool headed study and assessment: it's even been done already: in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development Heads of State and Government solemnly decided to establish networks of marine protected areas by 2012 and to rebuild degraded marine ecosystems by 2015 so that they can produce maximum sustainable yield and be net contributors to the economy and to society at large.

Well, you are forgiven to think that there is some urgency to act by now, because not much has happened since the decision was taken.

But not all is lost. Here are some action points - preferably in cooperation:

But not all is lost. Here are some action points - preferably in cooperation:

- Buy insurance against risk and uncertainty by creating marine protected areas;

- Value our great grand children’s fish as their fish, not ours;

- Integrate economics with ecology and other disciplines;

- Reduce sectoral approaches in preference to those that cut across all activities of society;

- Stop bad government subsidies to fisheries – Asia US $ 11.5 billion, Europe $ 5 billion, Latin America and Caribbean $ 4.5 billion;

- Help establish effective marine protected areas – the Convention on Biological Diversity foresees to protect part of the oceans - some progress - yet less than 1% are protected (probably 0.1% effectively);

- Promote sustainable forms of small-scale fisheries, recognise cultural diversity;

- Help enforce the law and stop impunity;

- Work on integrating sustainability principles, sciences and arts into curricula (university, lifelong learning, schools,...) and engage with opinion leaders;

- Meet our global peers and learn to collaborate

- Make scientific knowledge more widely available in the public domain;

- Encourage story telling and registration of memories to build bridges between different knowledge communities for mutual recognition and ability to cooperate on shared challenges.

Conclusion: science is important, even indispensable, for understanding, but ultimately, whether we change course and prefer protecting the sea from current widespread abuse is a societal decision, not a scientific one. The Powerpoint presentation is available here.