by Prof. Sarah Keene Meltzoff

Department of Marine Ecosystems and Society

Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science

University of Miami, USA

An original version of this case study grew out of the invitation from Prof. Paul Durrenberger to contribute a chapter to his book, State and Community in Fisheries Management: Power, Policy, and Practice (Durrenberger and King eds. 2000).

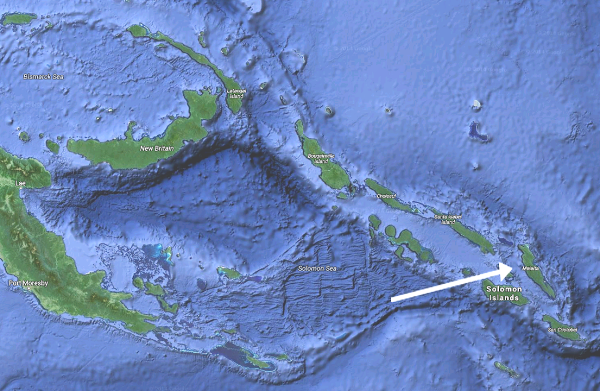

2000 Meltzoff, S. K., Nylon Nets and National Elites: Alata System of Marine Tenure Among the Lau of Fanalei Village, Port Adam Passage, Small Malaita, Solomon Islands". Invited Chapter in Durrenberger, E. Paul, and Thomas D. King, eds. 2000. State and Community in Fisheries Management: Power, Policy, and Practice. Westport, CT:Greenwood Publishing. 69-82.

Tiny jewels lie on the wet sand, jet black dotted in iridescent blues, yellow and orange stripes, green-red patterns. These miniature reef fish have been trapped by the small-meshed large nylon net now heaped in the front of the canoe. They mirror the thin catch carpeting the four-man dugouts which used to come home loaded. As the fishermen divide up the fish, girls swoop down to claim the juveniles. Digging holes by the canoe, they play at burial, marking graves with coconut fronds. Smaller kids toss the wiggling colors in the air. Some more children arrive with fishing poles, and recycle a few as bait. They’re headed for the tide pools along the fringing reef on the east shore of Fanalei’s island.

Until the introduction of modern nylon nets and access to an urban cash market, the alata system conserved the shallow reefs, and these juvenile fish, under the stewardship of the chiefly clan of Fanalei. Alata is the traditional or "custom" marine tenure system among the Lau “saltwater” people. This case explores how the fishing village of Fanalei on Port Adam Passage, Small Malaita, has altered their alata and customary use of reef resources. By setting the alata system into historical perspective, we understand the perpetual social, economic, political and environmental changes that interrelate and are constantly evolving Fanalei reef fisheries.

My multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork in the Solomons Islands started in Fanalei and Sa’a Villages of Small Malaita in 1973 (thanks to Thomas J Watson Fellowship), with the privilege of observing transformations in island life during the final years of colonial rule. This led to my dissertation fieldwork in cultural anthropology at Columbia University, NY (thanks to ICLARM and the Rockefeller Foundation), followed by periodic fieldtrips through 1992. The ethnographic present for this case is 1988, when frantic alata net-fishing for cash was at its height.

"Civilization"—the Pidgin English term for the modern world of machines and manufactured goods, used in opposition to "custom"--came riding in on the coat-tails of British colonialization. The Solomon Islands were officially claimed by Britain in 1893. Civilization demanded Pax Britannica as part of the program of British direct rule to end the constant headhunting and raiding. “Civilization” also required that islanders enter into a world where cash is not only desirable but necessary. The British intentionally triggered the necessity for cash by imposing head taxes. The District Officer of Malaita would patrol and collect head taxes as well as illegal guns to tame this most dangerously wild place of British imagination where cannibalism was real.

When Independence arrived in 1978, at the end of the global colonial era, Britain seemed glad to divest. They had never developed extractive wealth or significant infrastructure for the Solomon Islands population now exploding. In 1972, on winding down colonial rule, the British made an effort to create a font of foreign exchange through a tuna fishing joint venture with Japan’s Taiyo Gyogyo—the world’s largest fishing company. (Meltzoff and LiPuma 1982) The skipjack pole-and-line fisheries of Solomon-Taiyo was supposed to become the major source of GNP for a budding nation-state dependent on foreign aid. But the story didn’t unfurl this way because Taiyo, a vertically organized company, declared joint venture losses for at least the first decade of operation, despite fine catches.

Solomon Taiyo, however, did become a popular alternative source of jobs in lieu of plantation labor. The “saltwater” youth of Fanalei immediately hired on as skilled fishermen. "Civilization” trumping “custom”, migrant labor instead of warfare had become the established social norm. Village desire for cash only escalated with Independence. Given such forces of change, the Lau's alata system and fishing within Port Adam Passage was primed for a drastic sea change.

--------------------------------------

(1) This paper is in honor of Wilson Ifunao. In 1973, he returned home from University of Papua New Guinea where he had studied Anthropology. I, too, having just finished college, arrived thanks to winning a Watson Fellowship to live anywhere in the world for a year. A Margaret Mead fantasy and a yearning for tropical seas landed me in the Solomons. Honiara was then a tiny palm-fringed British colonial capital set in American wartime architecture, roads, bridges, and linked to the outside world by WWII’s Henderson airfield. Honiara’s population was just 7,000 in a archipelago of about 200,000 people. And, Wilson was only one of just five Solomon Islanders with a university degree. He had just started working for government when he took me under his wing. He was warm and funny, deeply intelligent and thoughtful about the social change he was leading. We became friends and he invited me to go live in his traditional “saltwater” village, Fanalei, where his father was chief. A few years later, Wilson almost came to Stonybrook for his Ph.D. in anthropology. While a graduate student at Columbia, I was about to pick him up at the airport when he telegraphed that the Solomons government had just offered him too important post to turn down, the first in a distinguished career. Wilson and his wife from the Northern Lau, raised children who, in turn, are national elite. Many of Wilson’s siblings and cousins and their children are national elite. Wilson was an extraordinary member of an amazing chiefly clan, and a leader of its first generation of national elite. He died of heart trouble in 1996.

All photos by the author except for the overview map.

Alata System

Lau from northeast Malaita originally migrated down to Port Adam Passage at least twelve generations ago, yet maintain close social ties. The Lau brought down their fishing-based culture, including powerful spirits for calling in fish and hunting dolphins. They transplanted the alata system.

As they settled Fanalei, a natural island at the south entrance to Port Adam Passage, they started creating alata--reefs historically recognized as good fishing grounds that are declared clan property. At the far north end of the passage, some of the Lau built an artificial coral islet--for which the Lau are noted—creating the sister fishing village of Walande.

Controlling access to the Passage, the Lau drew a sharp distinction between themselves and the Sa’a-speaking “bush” people who inhabit the mainland of Small Malaita. Lau and Sa’a people sometimes intermarried to increase access to each other’s specialized resources from saltwater fishing and bush gardening.

Saltwater and bush clans around the Passage mostly fought among themselves, the weaker clans hiring ramos as mercenaries for protection. Ramos earned respect and custom wealth, from reef and land rights to fathoms of red shell money--beads drilled from spondylus shell that are Malaitan custom wealth like dolphin teeth. Lau clans dominated Sa’a clans in the raiding warfare.

Saltwater and bush clans around the Passage mostly fought among themselves, the weaker clans hiring ramos as mercenaries for protection. Ramos earned respect and custom wealth, from reef and land rights to fathoms of red shell money--beads drilled from spondylus shell that are Malaitan custom wealth like dolphin teeth. Lau clans dominated Sa’a clans in the raiding warfare.

The Fanalei clan with the most powerful ramo became the chiefly clan and accrued the alata. Older chiefly clan members still recall fight stories that describe how they won the alatas from weaker Lau clans as payment for protection. These fight stories today can justify political power and property rights. But if mentioned in public in front of those clans who had to hire ramo, shame and anger surface. The stories have poignant ability to spark brawls among young men who head off to labor where everyone mixes, are not entrusted with fight stories until they are safely home and not tempted to one-up each other socially with such volatile custom knowledge.

According to Lau custom, an alata was created by the first man to have a team set his own huge net around an unclaimed reef and haul in a plentiful catch. This net-owner gained the right to name that reef as a new alata for his clan. Only someone powerful enough to transport the net with the requisite giant canoe and be able to control a net-fishing team could establish an alata.

Pax Britannica froze alata ownership in perpetuity. Weaker clans no longer hired ramo who could demand payment in alata. In the days of ramo warfare, the clan leader was often the ramo. The clan payback “fight” system had left today's Fanalei chiefly clan holding all alata.

Today's alata cannot be transferred without the consent of the clan as a body. Stewardship of an alata is ceded to an individual clan member, but married women are excluded from being named as the alata “owner”-- the steward. In Fanalei, the “owner” is the chief.

Technically, only the clan that owns the alata can use it for activities other than net-fishing, such as spearfishing, line fishing or shell-diving. It remains taboo for someone outside the clan “to fish all about” in an alata--such behavior carrying a compensatory custom fine. Clan ancestors are thought to reveal steward if someone is poaching to the alata “owner”. Canoes were not permitted to pass over alata but had to travel through the channels, inadvertently protecting shallow corals from paddles, and now outboard motors.

Adi--a special fishing ban inside an alata for six months up to two years--is a central control mechanism within the alata system. In between net-fishing on a particular alata, the owner could impose an adi to reserve fish stocks for a special occasion like a feast or to barter for custom wealth needed for a bride price.

Calling for an adi embodied the whole political-social-technological-economic-religious complex whereby the alata owner and his clan displayed and earned power and control. The Lau did not consider their alata system to be management per se, with the attendant concept of conservation. Yet in current management terms, it functioned to limit fishing effort as a corollary to their cultural sense of power. Thus Lau used the system to store up fish in exchange for custom wealth/an event, or to gain political largess through magnanimously granting fishing permission to other clans.

Fishing the Passage Alata Prior to WWII

The net owner would organize his own clansmen to be in the two large canoes--typically for 20 men--that carried and set the giant net. Smaller canoes were allowed to join in and form the flotilla. One large canoe let out the net about half way then paid out the rest of the net to the other canoe. As the two large canoes encircled the alata, a couple of men would jump down into the sea at either end of the net, setting the circle’s slopping bottom, and report on the quality of fish inside.

A net haul was big enough to be measured by the number of 10-man canoes--ae garua--filled with fish. The net owner would divide the catch. Those who went out to the reef earned the biggest portion of fish, although the abundance was shared among all village families. Except for the dangerous garfish, once a fish was pulled out of the net and was flipping around inside a canoe it was forbidden for someone to claim it. Returning to the village, each fisherman carried some fish to the tohi--prayer house--where they roasted the smaller ones and boiled the larger ones as a sacrifice to the spirits, including Jesus who leads the ancestors once they were missionized by the Anglicans. Regardless of clan, all village men could partake in the offering, but not women. Then the net owner divided up the uncooked catch.

A net haul was big enough to be measured by the number of 10-man canoes--ae garua--filled with fish. The net owner would divide the catch. Those who went out to the reef earned the biggest portion of fish, although the abundance was shared among all village families. Except for the dangerous garfish, once a fish was pulled out of the net and was flipping around inside a canoe it was forbidden for someone to claim it. Returning to the village, each fisherman carried some fish to the tohi--prayer house--where they roasted the smaller ones and boiled the larger ones as a sacrifice to the spirits, including Jesus who leads the ancestors once they were missionized by the Anglicans. Regardless of clan, all village men could partake in the offering, but not women. Then the net owner divided up the uncooked catch.

Since the 1930s, the relatively small population of Fanalei could only own and operate one large custom net at a time, while Walande has enough men to operate two. Custom nets were made of inner bark and took several years to role the line and knot the mesh. Yet the massive net lasted just one year. Net ownership on Fanalei rotated from one clan to the next, all clans participating in net ownership. Fanalei only set their large custom net about four times a year for feasts. The net owner who wished to fish a particular alata had to ask permission of the alata “owner” and pay one fathom of red shell money or promise the owner’s wife a large share of the catch that she could market. Bush villagers--who fished little themselves even in 1980--competed with each other over whatever fresh fish or dolphin meat is traded at the Passage markets on the mainland. Bush people would “sing out” the arrival of the saltwater women paddling in their canoes laden with catch. Both bush men and women exchanged their garden and bush products eagerly for the fish.

Saltwater-Bush Competition Fishing the Passage

When Fanalei and Walande’s Lau ancestors discovered the sheltered Passage and claimed its rich reefs for their alata, it had been uncontested by Sa’a “bush” people. Bush culture focused on gardening in the hills arching up from the Passage. Hills also provided a degree of safety from Lau raids. The “saltwater” people were notorious fighters and took early advantage of mid-nineteenth century Blackbirders--colonial plantation labor traders carrying off people as far as Fiji and Australia--to earn guns and other “cargo”—manufactured goods--by delivering bush to the traders. Long after colonial government was firmly in place and Pax Britannica reigned--guns and payback fighting banned--the Lau gladly retained their fierce reputation. Even on the eve of Independence, the Lau were boasting of their prowess over the “bush” people who assiduously continued to avoid fishing inside the Passage.

During my first fieldtrip to Fanalei in 1973, I loved paddling across the Passage and snorkeling the shallow reefs, and never saw Sa’a fishing. An occasional bush relation came to join a Lau net-fishing team, but only the Lau were culturally organized for net-fishing around the alata. Besides, bush people still lacked even small dugout canoes for individual gill-netting, diving, or hook-and-line fishing inside the passage. When a bush clan needed fish for a feast, they came to ask the chief at Fanalei to send out a team to fish one of his alata for them. The bush clan that made the request was granted the largest share of the catch, with the rest of the catch divided among the net team. If they were affinally related to Fanalei--intermarriage being common—they could reciprocate with garden crops. Otherwise, they had to present the chief with a one fathom of red money, or porpoise teeth, or even cash as compensation.

Around 1975, population pressure on garden land had reached a point where individual “bush” men were daring to venture into the passage for subsistence. This initiated the first marine resource competition between the Lau and Sa’a inside the Passage.

Around 1975, population pressure on garden land had reached a point where individual “bush” men were daring to venture into the passage for subsistence. This initiated the first marine resource competition between the Lau and Sa’a inside the Passage.

By the late 1970s, a few “bush” men were turning their trees into dugouts for their own use. Tension over Passage fishing rights marked the loss of Lau dominance. Terrible in Lau eyes, “bush” people along the Passage started pressing for official fishing rights in Custom Court that hears contested land/marine tenure cases. In Custom Court, clans can prove ownership by citing ramo fight stories.

Publically Lau have scorned the idea of ever being asked to pay compensation to bush clans for marine use. Pointing to their loss of power to control Passage waters with conflicting emotions, a few Lau tell me it signaled the coming of “Brotherhood taught by the Church”. Most Lau, however, felt “cross”--angry--that it was coming at such a steep cultural price saying, “Bush” people might stop fearing and respecting Lau warriors."

By the mid 1980s, bush fishing continued to escalate. I could compare the percentage of Sa’a versus Lau dugouts inside the Passage on any given Saturday--the day to secure fish for Sunday. Fanalei's Anglican Church forbids all work on Sundays, including spearfishing on picnics. So on calm weather Saturdays, Lau fishermen left the Passage far behind, ranging far to sea. More Sa’a than Lau fished inside the Passage on these Saturdays, emboldened on by their own numbers.

It reached the point where local politicians felt they could win votes by joining sides with the Sa’a bush majority. During the 1986 South Malaita Parliamentary elections, candidates campaigning in bush villages even promised that they would take back control of the Passage from the Lau and repatriate the Lau to North Malaita.

As population growth surged beyond the capacity of slash-and-burn agriculture in the fragile, thin-soiled, hilly rain forest on the mainland, land ownership and questions of rights to marine resources rose to the fore. Land-poor clans, whether bush or saltwater, were facing a tight subsistence situation, turning to the sea and cash. Population pressure was reflected in ever-increasing numbers of custom court cases contesting land and reef tenure.

“Feeding the People”

Owning the 120 foot custom net had been contingent on simultaneously owning the canoe large enough to transport it. Village leaders including the net specialist/owner, must still possess such a mighty canoe. Always prized, the giant dugout imbues the owner with powers parallel to the alata and the net itself for “saving people” and “feeding the people.”

The giant canoe has been critical during cyclones, war, and times of sickness to move people to safety. It carries the dead home, as well as to the graveyard on the mainland. And for islanders, much like a truck in the world of roads, it performs essential heavy duties such as transporting house posts, fat pigs, the 30 gallon fuel drums, and 50 kg sacks of rice and flour. When people must travel in groups, they turn to this canoe owner who gains political prestige, alliances, and perhaps direct compensation for providing transportation for the people.

The giant canoe has been critical during cyclones, war, and times of sickness to move people to safety. It carries the dead home, as well as to the graveyard on the mainland. And for islanders, much like a truck in the world of roads, it performs essential heavy duties such as transporting house posts, fat pigs, the 30 gallon fuel drums, and 50 kg sacks of rice and flour. When people must travel in groups, they turn to this canoe owner who gains political prestige, alliances, and perhaps direct compensation for providing transportation for the people.

A canoe giant has required a massive tree, found either growing on clan land, or by paying another clan for their tree. And one must then be able to organize labor to first hollow and then haul the rough leviathan down to the seashore, a process that can take up to two days, depending on the tree’s distance up in the steep hills, the group's skills, and the tides.

Resource competition due to overpopulation includes competing for the ever scarcer huge trees. Where rain forests were thinning in the in the 1970s, satellite images on Google Earth as of 2014 show fragile red earth. Fanalei's chiefly clan owns more land, as well as alata, than other clans so has kept control of production. In a parallel to marine tenure, clan members must block others from felling trees and gardening on their land without seeking customary permission.

Story of the Last Ramo and his Bid to Power via the Giant Canoe

In 1988, Kumuli is the last ramo in the final generation of the Fanalei chiefly clan to create a ramo—demanding inheritance of the berserk propensity as well as the custom initiation. Kumuli is seeking to build up his political prestige in the Passage through the custom channels of “saving people” with his new enormous dugout for which he has purchased one of the still relatively rare outboard motors.

One day on their clan land in the mainland rainforest, his wife, Tama, accidentally comes across a felled giant tree that lies half hollowed out into another dugout. Kumuli flies into the ramo custom rage, finding the responsible clan and commanding them to abandon the giant, leaving it to rot. Kumuli has forbidden them access to the tree that threatens his own canoe meant to establish his base of economic and social political power.

One day on their clan land in the mainland rainforest, his wife, Tama, accidentally comes across a felled giant tree that lies half hollowed out into another dugout. Kumuli flies into the ramo custom rage, finding the responsible clan and commanding them to abandon the giant, leaving it to rot. Kumuli has forbidden them access to the tree that threatens his own canoe meant to establish his base of economic and social political power.

Although the other clan must obey Kumuli's order because of land rights, they circumvent his intention by purchasing one of the large fiberglass canoes from the government’s new fiberglass canoe-building program. Fiberglass--like nylon for nets--opens up a cash-based option for attaining power via ownership. Few in the land-poor clans can afford the $2,000 price tag for this manufactured “cargo” alternative to owning giant trees, but several wage-earning village teachers can purchase these modern canoe alternatives instead.

The design, however, is an orange fiberglass with covered bow, elongated body and straight-backed stern that is completely incompatible with paddling and net-fishing. Compared to dugouts that have the flexibility to be either paddled or motorized, the fiberglass canoe needs an outboard engine. In a place outboards perpetually “bugger up”--break down--in the salty, reef-ridden Passage environment with minimal maintenance, this is a serious handicap. Mechanics are rare and spare parts scarce, so most engines remain out of commission for long periods of time. Kumuli ironically is one of the few villagers trained as a mechanic during his years away from home.

Fiberglass canoes, when the motor is running, can bring political and financial rewards to the owner who undertakes all the social service tasks that “save people”. Except for alata net-fishing, fiberglass canoes disassociate the act of “saving people” from the act/fact of being in a dominant land-rich clan. Fiberglass canoes and nylon nets come from cash-based social political-economic "civilization", diminishing the power of owning alata and land with giant trees.

Exchanging Custom Fiber Nets for European Robber Nets

Custom net specialist/owners, also owning the requisite giant canoes, were known as “saving people's lives” and “feeding the people”, and ruled with an iron hand in the days of warfare. The relatively small population of Fanalei after WWII could only own and operate one large custom net at a time, compared to Walande’s denser population running two nets at the far north end of the Passage on their own alata. Fanalei’s last handmade fiber net rotted around 1960. Interest had shifted away from the wealth displays of feasting--which demanded big hauls of fish. Over the next decade, people focused more and more on individual cash pursuits (e.g. copra and pig production) even though the cash would end up shared within the clan.

Nylon mesh gill-nets were introduced by the Fisheries Department in the 1970s and the saltwater Lau were eager to have them. The Lau dubbed them "European robber nets" because they could sneak up on the reef fish and steal them. They hoped these manufactured “cargo” nets would have European powers in a parallel with colonial power, and be optimally, almost magically, effective. “European robber nets” are seen as relatively invisible under water, besides being stronger, breaking less frequently, and making more constant fishing possible by lasting much longer than a bush fiber net.

Nylon mesh gill-nets were introduced by the Fisheries Department in the 1970s and the saltwater Lau were eager to have them. The Lau dubbed them "European robber nets" because they could sneak up on the reef fish and steal them. They hoped these manufactured “cargo” nets would have European powers in a parallel with colonial power, and be optimally, almost magically, effective. “European robber nets” are seen as relatively invisible under water, besides being stronger, breaking less frequently, and making more constant fishing possible by lasting much longer than a bush fiber net.

In 1974, when the Fanalei Village Fund led by the chief purchased one of the Fisheries Department's new nylon nets, locals criticized its rectangular shape. Fanalei’s old custom net specialist/owner set about reworking the nylon to give it the belly of the custom net. Encouraged by Anglican sermons on unity, Fanalei villagers did try a novel approach, making it a Village Nylon Net, having been bought with Village Funds and thought to be imbued with European power. The new nylon net, however, failed, disintegrating since nobody was granted the responsibility for its care. It had lacked a guardian in contrast to a custom net that always had a designated net specialist/owner whose prestige and power directly benefited from his custom knowledge and discretion.

Everyone initially treated the large nylon net from the "cargo" world as separate from custom, not needing fishing spirits or specialist/owners. Yet watching this nylon fail, they quickly tried to incorporate it into custom. The chief assigned a specialist/owner, who has remained the net specialist/owner for the Fanalei's subsequent large nylon nets. Most important, the sacred bird float imbuing spiritual power—which traditionally marks the central belly of the custom net in the water—started being stored with the nylon net to lend power. Therefore, in good syncretic fashion, they melded the “cargo” mystique, of the European robber net with the all-important strengths of the net specialist/owner, guardian of local spirits and gifted with the ability to give the proper belly.

Fanalei’s Chiefly Clan and its Salaried National Elite

Since the onset of colonialism and the cash economy, Fanalei’s chiefly clan has been aligning itself with the outside economic and political powers. They started assisting the new British patrolling district officers who preferred recruiting from powerful clans. A disproportionate number of chiefly clan children set off to Anglican boarding schools to learn the new ways of power. As a corollary, by the late 1980s, almost all Fanalei’s salaried national elite hail from the chiefly clan.

As the core source of cash, credit and “cargo”, the elite have direct influence over their chief who is in charge of local political clan alliances. Thanks to cash and access to credit, chiefly clan members can continue acquiring land and broadening their power base, cementing alliances. In this manner, the modern day ramo system perpetuates itself. These enterprising “home” members buy land for cash-cropping copra and pig farming, reinvesting proceeds in more land, building on local friendships and custom fight/political alliances with bush clans, besides continuing to help out with compensation payments in ongoing feuds. National elite members also have been able to purchase land from their extended national network of alliances and friendships, procuring large tracts outside of Small Malaita (e.g. on Makira, SE Solomons). The Fanalei chiefly clan’s continued control of land as well as the alata has spiked jealousy in the other village clans.

As the core source of cash, credit and “cargo”, the elite have direct influence over their chief who is in charge of local political clan alliances. Thanks to cash and access to credit, chiefly clan members can continue acquiring land and broadening their power base, cementing alliances. In this manner, the modern day ramo system perpetuates itself. These enterprising “home” members buy land for cash-cropping copra and pig farming, reinvesting proceeds in more land, building on local friendships and custom fight/political alliances with bush clans, besides continuing to help out with compensation payments in ongoing feuds. National elite members also have been able to purchase land from their extended national network of alliances and friendships, procuring large tracts outside of Small Malaita (e.g. on Makira, SE Solomons). The Fanalei chiefly clan’s continued control of land as well as the alata has spiked jealousy in the other village clans.

Overall, people have feared tensions created by cash access. The concept of “private” individual accumulated wealth and ownership has been alien and is slow to change. People must share to keep honor, prestige and power. In the act of creating social debts used for alliances, people are considered “generous”. Given the cultural importance of sharing possessions and not taking them as personal property, a selfish person is bluntly called “rubbish man” in Pidgin. In village life, nobody wishes to elevate their material possessions/standard of living far above others. In fear of the “jealous business,” they forego showing off with an abundance of manufactured luxuries, such as mattresses, propane stoves, and fiberglass cisterns to collect rainwater.

Sensitive to the dangers of “jealous business”—the universal evil eye--those with salaried jobs in Honiara told me how they are focusing on the Anglican Church's coupled message of village unity and cash development that avoids competition among clans. The chiefly clan hopes to promote unity through village development in a way that limits interclan rivalry. Yet they still wish to keep up their custom power of “feeding the people” in order to hold onto ranked power and respect. This makes for a difficult move when it comes to managing reef resources, but managing is not on the conscious agenda at this time.

The chiefly clan and their national elite synchronize actions bent on lowering village tension over the cash disparity. They discuss how the other Fanalei clans, who have been less fortunate than themselves, are land-poor and in danger of growing hungry as population pressure on resources in the Passage soars. Wishing to address increasing jealousies at home, they devise a plan to turn alata net-fishing into a cash-making venture for everyone in Fanalei. They hope to translate the custom power of “feeding the people" with giant canoe and net into the modern vernacular of “feeding the people” via a village-wide opportunity to sell alata reef fish.

To this end, the Fanalei national elite based in the capital of Honiara on Guadalcanal buy the village a large used nylon gill-net with illegally small mesh. They cart a large ice chest—eski—to the Honiara wharf and load it onto the listing vessel bound for Malaita. Crossing in the night, circling Malaita and returning to Honiara, it makes this voyage perhaps three times a month. The Fanalei elite alert their home village to expect the ice chest by placing a public announcement on the nightly national radio program. Around the archipelago, villagers stay tuned to this pan-Solomons evening news in a world before cell phones and internet. Their population is still relatively tiny and the degrees of separation are small enough to pass on everything from family deaths to shipping news.

Thus forewarned, Fanalei prepares by net-fishing the alata. They will be standing by with at least 50 kg of fish to fill the eski and put it right back onboard bound back to the cash market. The Fanalei elite carry it to the capital’s fresh fish market where all sells simply.

It seems so easy, with no forethought to overfishing reefs. The alata has always yielded fish. Nobody pays heed to the wildly increased frequency of fishing. Cash is coming into Fanalei as envisioned. Mirroring power to “feed the people,” the Fanalei national elite feel they are expressing largess by running this market that promotes village-wide cash development. Everyone feels it's a success.

Passage Circa 1988

But with constant fishing, the sizes of the average alata reef fish rapidly diminish. The ice chest is not yet due in Port Adam Passage, yet a group, including me, paddle out in small dugout canoes, following the large dugout of the net owner/specialist bearing the large small-meshed nylon net. He leads us to the first of several alata he has selected for today’s harvest. He realizes it will take more than one site to catch enough to literally feed villagers, today’s goal.

At the first alata, most of the men jump down into the water, churning legs, treading water, stepping on and inadvertently breaking corals in the deeper spots while trying to keep heads above water. They anchor the net’s belly with the nito--the rope running to a stone which holds the belly to the bottom. And the spirit bird float is set to mark the spot. Eagerly, they set the net and draw both sides to surround the alata. Then everyone slowly walks the net walls into a tightening circle around the frantic fish.

Back on the beach, the catch is "shared out" into piles, one for each who worked the net. The net specialist/owner supervises the distribution of piles, allotting roughly equivalent sizes, types, and numbers of fish. The net specialist/owner allocates himself a bigger share. The average share has dropped to four kg of fish, like today.

A little boy and girl are squatting in the wet sand near the people offloading the canoes. They are playing at fish distribution, carefully arranging the brilliant tiny juveniles into flipping rows as their relatives deal out edible sizes.

Villagers willingly sacrifice these baby fishes who cannot escape the mesh. They literally see how a quarter of their catch would escape through changing to a net with larger mesh size. The Fisheries Department sells nylon nets in various legal mesh sizes, but there is no enforcement of mesh size regulations. The Lau do not weigh how their mesh size risks decimating alata reef populations. Nor do they consider returning to limited alata net-fishing, given the lure of cash from the ice chest. Besides, the Lau hold other beliefs as to why alata fishing is crashing. They insist absolutely that there is no connection between increased fishing effort and decreased catches.

Villagers willingly sacrifice these baby fishes who cannot escape the mesh. They literally see how a quarter of their catch would escape through changing to a net with larger mesh size. The Fisheries Department sells nylon nets in various legal mesh sizes, but there is no enforcement of mesh size regulations. The Lau do not weigh how their mesh size risks decimating alata reef populations. Nor do they consider returning to limited alata net-fishing, given the lure of cash from the ice chest. Besides, the Lau hold other beliefs as to why alata fishing is crashing. They insist absolutely that there is no connection between increased fishing effort and decreased catches.

Overfishing is not one of their concepts. Local perspectives on the causes of current catch failure are rooted in the custom political, religious, and social powers embedded in the alata system. The Lau can fault the spiritual powers of the nylon net and alata to explain scanty catches.

They are staunch syncretic believers in Jesus who resides at the head of their pantheon of ancestors and spirits. As in dolphin hunting, they blame individuals among themselves who can offend the all-important spirits credited with bringing in the fish. Certainly, the Lau condemn their “bush” rivals for harming the catch. They tell me how the bush men are fishing daily inside the Passage which frightens spirits and drives reef fish into deeper places.

In Honiara, I discuss management and the potential of the alata system with the top British fisheries officer. He says, "The Fisheries Department realizes there’s a lot of village fishing with the illegal mesh sizes. And we know that villagers don't leave time for reef recuperation. But we are lacking funding for a management mission and enforcement."

His solution, as Fisheries, is as predictable as the reef net-fishing situation, itself. Fisheries will bank on an economic model of diminishing returns that relies on a hands-off market solution. He predicts, "Villagers will stop overfishing once they cannot fill the ice chest enough to make it economically viable to send to Fanalei."

Reef management that reckons on an economic crash to control fisheries is a common pattern worldwide. Yet it is unsophisticated, lacking confidence in developing grassroots involvement in self-management. This is especially the case where there already exists the tempting reef-controlling alata system imbedded in the fishing culture.

Fanalei's national elite, for their part, are not talking about reef conservation or management planning for their alata, let alone approaching Fisheries for advice. They do not want to debate the frailty of reef ecosystems and sustainability, although a few of them already intellectually understand the concepts of marine ecology. Rather, as an elite clan group, they are torn over whether to ask their chief as steward of the alata to step in and reinstitute custom reef rights and the adi for the sake of reef survival. At home on Fanalei, villagers discount any ecological consequences of their intensive fishing for cash on the alata.

At this point, nobody contemplates how to use the alata system for reef conservation and management as stocks dwindle and seem to disappear.

Now the highly destructive fishing practice of gill-netting is spreading inside the Passage with the use of individually-owned and run little nylon gill-nets The Lau are buying up these illegal small-mesh nets second-hand from other villages. They are starting to set these smaller nets all around the Passage, but outside the alata. These “European robber nets” are a new causal factor for declining reef catches and are causing major social change because of their low cost and ease of solo use outside the custom alata system.

One man can set his own gill-net, anchoring it in place, and later hauling it in by himself. Even a relatively cash-poor person is able to purchase a used one for his nuclear family. As the net owner, he can place it almost anywhere in the Passage except in an alata, without special skill or permission. Others outside his nuclear family borrow the gill-net in return for a share of the catch, keeping it active in the water, ensnaring random fish by their gills.

The owner can leave his gill-net anchored on a reef overnight and longer. He and even his female family members including children can paddle out, don goggles to remove the catch, and leave the net in place if it seems productive.

Women's blood from childbirth and moon cycles in Malaita harbors overwhelming custom strength to harm spirits, especially those who bring in the fish. Note that ethnographers from European and American male-dominated cultures began calling the common global phenomena female "pollution". However, it is important to change jargon and emphasis. Female "powers" is a far more accurate way to reframe the phenomena since it is based on custom fear of female procreative blood's spiritual powers rather than on it being conceived of as dirty/foul.

Female procreative powers cannot injure the efficacy of the non-traditional nylon gill-nets which are outside the influence of custom skills and spirits, impersonally manufactured, and seen as foraging/collecting rather than as fishing/attracting. The novel gill-netting is being labeled "foraging" instead of fishing, foraging classically practiced by women and unmarried girls, who seek shellfish and octopus.

Given female powers, it was taboo for women to go custom net-fishing, or fish with the large nylon net that is being stored with the bird spirit. Yet as the alata yields less fish, unmarried young women, like me, are permitted to join the frequent net teams if there are not enough men. Overall, there is more leeway for unmarried women to participate as a team share shrinks, and as spirits are thought to abandon a fishery or not be a part of it.

Adi and its Potential for Gassroots Alata Management

Subsistence shelling along the mangrove shores of Fanalei island and the Passage is uncontrolled by adi. Mangroves have always been left open for women and girls foraging edible shellfish. They collect three prime edible types of oysters and clams that grow around prop roots. Lau women trade these shellfish with bush women for root crops, such as yams and taro.

The introduction of dive goggles circa 1925, allowed people to see and harvest effectively and efficiently underwater. The introduction of goggle technology by coincidence corresponded with the pre-WWII international market demand for pearl shell buttons, bringing Chinese and German buyers into the Solomons. Lau in Port Adam Passage, unlike their northern Lau relatives, were motivated by cash to switch to imposing adi for the marketable pearl shells, ending adi for net-fishing.

The introduction of dive goggles circa 1925, allowed people to see and harvest effectively and efficiently underwater. The introduction of goggle technology by coincidence corresponded with the pre-WWII international market demand for pearl shell buttons, bringing Chinese and German buyers into the Solomons. Lau in Port Adam Passage, unlike their northern Lau relatives, were motivated by cash to switch to imposing adi for the marketable pearl shells, ending adi for net-fishing.

The Fanalei chief as steward of the alata still calls for pearl shell adi to build up stocks and reserve rights to this cash commodity. Unlike fish, pearl shells are non-perishable and simple to stockpile for sale. Anyone, whether they come from the chiefly clan or not, can ask the chief to let them be an adi-maker. Either sex can be an adi-maker since both saltwater men and women can forage.

To begin the ban, the adi-maker places a stick out on the reef and tells everyone which specific shells and other marine life are included in this adi, and declares how long the ban will last. But because of the introduction of waterproof flashlights for night diving, adi poaching has increased and become a problem.

When the adi is over, the adi-maker announces the opening day of harvest. If the adi-maker is not from the alata owner's clan, he can accompany the adi-maker on this first day as a form of compensation payment. Anyone else who wishes a share, donates two days of labor to the adi-maker, with the third day's harvest as payment. There are always some divers who collect less diligently in order to have more to harvest for themselves at the end.

Fanalei’s transition into intensive weekly net-fishing has been in line with village practices since their adi for net-fishing ended before WWII. This has left alata reef fish without any stock recuperation/ conservation bans. If Fanalei's alata owner were to reintroduce the adi for cash net-fishing, villagers might easily reincorporate the cultural logic of their adi.

Conclusion: Grassroots Reef Conservation

The alata system has embodied a nexus of technological-social-religious-economic-political power relationships. With civilization in the modern independent nation, Lau culture and its alata system are losing custom interrelationships. Cash net-fishing for the ice chest is making the alata ineffectual at conserving resources.

Meanwhile, gill-netting by individuals with their own inexpensive small-meshed nylon nets is spreading around the Passage. Fanalei fishermen eagerly set these little gill-nets, following the interest of Fanalei's national elite in bringing more cash into the village by promoting net-fishing. This destructive new fishery, however, falls outside the realm of the alata system.

Fanalei's chiefly clan's, owning the alata and land with giant trees, has national elite members lending them access to cash and credit unlike the other clans. They aim to reduce the risk of the other clans' jealousy. So they have acted to share their custom resources and some power gained from “feeding the people.”

Fanalei's chiefly clan's, owning the alata and land with giant trees, has national elite members lending them access to cash and credit unlike the other clans. They aim to reduce the risk of the other clans' jealousy. So they have acted to share their custom resources and some power gained from “feeding the people.”

Because their clan plan for intensive cash net-fishing inside alata is not turning out to be viable, they still have the custom option to revive the adi for net-fishing--in parallel to the adi for foraging shells--and place alata net-fishing back under grassroots control. Unfortunately, escalating individual gill-netting is beyond the custom reach of the alata system. This might limit the potential effectiveness for saving Passage reef stocks of reintroducing adi for alata net-fishing.

Reefs all around the Passage are being depleted, population is rising, and saltwater-bush fishing conflicts are escalating. But Fanalei acting as a village under the chief as with the Village Fund--instead of granting largess in the name of the chiefly clan--could possibly reinvent the use of adi throughout the Passage. Fanalei might incorporate net-fishing bans on all European robber nets, large and small, group-run and individually owned, inside and outside the alata. This will call for some creatively custom ways of incorporating and controlling the Lau of Walande and the rising population of ever more aggressive Sa'a bush fishermen.

Sustainable village cash fisheries using adi would have to center around a new local control of the Passage. Success will need the buy-in of all Lau village clans in decisions for conservation bans then sharing the harvests. Passage-wide adi can gain cooperation and compliance if all clans believe that the adi fisheries will benefit their social political economic well-being. Ramo dominance and intimidation is over.

Note that management as a concept and construct of Fisheries in the Solomons has been top-down, without enforcement of regulations like mesh-size, relying on economic solutions to curb reef fishing for cash, as in Fanalei. So far there has been no effort at incorporating local beliefs and social organization.

Outside scholars and resource managers classically hold romanticized notions about “traditional” people and their conservation practices. Many have assumed that local “custom” fishers will manage their resources for long-term sustainability if left to their own devices practicing some folk system of management, without cash markets to lure them into overfishing.

Critical questions in untangling these assumptions need deep ethnographic understanding. First we recognize that a custom tenure system is not locally conceived of as management with the concomitant biological concepts of cause and effect from overfishing. Then we search for ways to encourage locals to work within their accepted custom system. The alata system is as an, albeit unconscious, management system that can still control access to local reef resources, and might even be expanded to ensure reef recuperation. Whether or not islands share national managers’ biological concept of intensive reef fishing causing overexploitation--biological cause and effect—may not be imperative for successful management. Fanalei islanders hold other concepts for reef fecundity in a world that holds spirits and rivalries to account. What matters is how to encourage local hierarchies to use their own custom reef control systems to organize and share grassroots conservation and its profits.