The first steps have been made to start dialoguing from one shore of the Atlantic Ocean to the other. It all started with a conversation about the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy in Senegal at the Slow Fish event in Genova in 2019. That had peeked Ana Isabel Marquez Perez' interest. As she organised the 3rd Festival of Traditional Navigation in the Caribbean with her team on her native Providencia Island for September 2021, she invited Mundus maris and members of the Academy in Yoff to exchange about the conditions of artisanal fishers and their boat building traditions.

The first steps have been made to start dialoguing from one shore of the Atlantic Ocean to the other. It all started with a conversation about the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy in Senegal at the Slow Fish event in Genova in 2019. That had peeked Ana Isabel Marquez Perez' interest. As she organised the 3rd Festival of Traditional Navigation in the Caribbean with her team on her native Providencia Island for September 2021, she invited Mundus maris and members of the Academy in Yoff to exchange about the conditions of artisanal fishers and their boat building traditions.

The island is part of Colombia, but located closer to Nicaragua, in the Caribbean. The Across the Big Pond, a video conference link was established twice. In the first occasion on 10 September, Cornelia Nauen of Mundus maris recalled that the Academy was intended to serve as operational support for the implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries. These had been adopted by the FAO Committee of Fisheries in 2014 after extended world-wide consultations, but were facing challenges in putting them into practice.

At the same time, artisanal fisheries were under increasing pressure in most countries as industrial fleets - often subsidised by their richer countries of origin - led to wisespread overfishing and resource degradation. West Africa had moreover become a hotspot for illegal, unregulated and unrecorded (IUU) fishing provoking decreasing income for local coastal fishers and significant loss of tax income to developing countries which can least afford such losses.

At the same time, artisanal fisheries were under increasing pressure in most countries as industrial fleets - often subsidised by their richer countries of origin - led to wisespread overfishing and resource degradation. West Africa had moreover become a hotspot for illegal, unregulated and unrecorded (IUU) fishing provoking decreasing income for local coastal fishers and significant loss of tax income to developing countries which can least afford such losses.

Strengthening the capacities of men and women in artisanal fisheries for enhancing their livelihoods through individual and collective action is the declared objective of the academy. Cornelia summarised the pilot phase which served to test the inclusive and active teaching methods which enabled all academy learners to participate in equal measure.

Each learning cycle starts with a vision to provide orientation and a sense of direction. The individual and collective action plans elaborated by participants and validated with family, neighbours and the community trace a change journey of initially one year towards achieving the vision. An example is provided by a short video on the YouTube channel of Mundus maris.

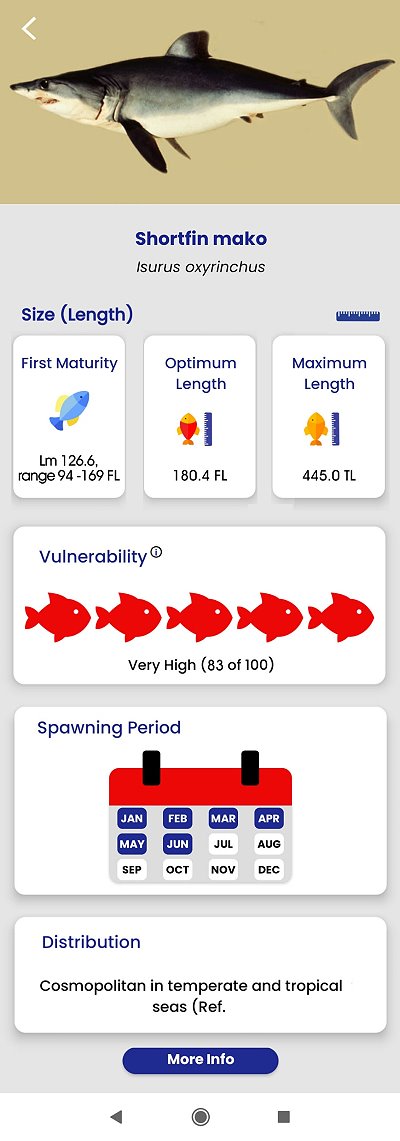

The academy as a safe multi-actor space for dialogue, joint learning, co-creation of knowledge and locally adapted innovation has also triggered some technical innovation. The latest takes the form of an app for mobile phones indicating the minimum length of a fish and the vulnerability to overfishing of a species by only indicating the country and typing a common name in whatever language.

That could help women in marketing fish in a higher value segment or even serve as a pedagogical tool in schools.

The slides in English of the talk in Spanish are available here.

Then, on 23 September, it was finally the time to establish a direct link between practitioners. True to the focus of the festival and the passion of many people in San Andrés on Providencia for racing sail ships, small and big, they were keen to learn about boat building on the other side of the Atlantic.

For the event, Aliou Sall of Mundus maris in Senegal had invited a master boatbuilder, Ibrahima Sylla better known as Ibrahima Thioye, a boat painter, Mamadou Sall also known as Mod Dia, Abdoulaye Gueye, a fisher, and Seynabou Diouf, a micro fish vendor, respectively President and Vice-President of the Academy committee in Yoff. Other committee members were the micro fish vendor Rokhaya Diène and the fishers, Abdoulaye and Papa Dial, the latter also a leading member of Freyr Yoff, a reputed local association. Finally, a PhD student researcher, Oumar Sow attended.

The boat builder reported how difficult it was to source the wooden planks for the traditional Senegalese pirogues, especially as they were getting bigger and drought in the Sahel country made wood a shrinking resource. The wood had come from The Gambia and Casamance in Southern Senegal in the past, but now planks might be sourced from Guinea or even Côte d'Ivoire. The bigger sizes in demand from owners deploying large encircling nets to catch small pelagics, such as sardinellas or bonga shad also demanded adapting tools and construction methods.

While boat building had originally been a matter of skills handed down through generations within specialised families, the demand was such that hands-on training was now common also for 'outsiders' who could make a decent living from the occupation.

Despite promotion of glass fibre boats by the government to respond to the wood crisis, fishers preferred wooden pirogues by a long margin, not the least because they were still significantly cheaper than the glass fibre boats.

In Providencia wood was also in very short supply and most fishers had long adopted glass fibre boats, which were much smaller than the Senegalese pirogues. Few wooden sail boats were still in operation, but a few were still raced, a passion also conferred to small wooden models of sail boats (see picture to the right).

In Providencia wood was also in very short supply and most fishers had long adopted glass fibre boats, which were much smaller than the Senegalese pirogues. Few wooden sail boats were still in operation, but a few were still raced, a passion also conferred to small wooden models of sail boats (see picture to the right).

The pictures of pirogues shown also triggered curiosity in relation to the colour patterns and painting. Modou explained that the main challenge was not applying the paint itself, but to perform the drawings in an interplay of his artistry and the demands of the clients. Some wanted a picture of the water goddess included, others that of a religious leader or specific symbols. In all cases, the paintings were characteristic of regional preferences and served as identifier of the pirogue.

Several questions were posed about the fisheries. Abdoulaye Gueye explained that broadly two types of fisheries could be distinguished in Yoff, the large pirogues operating the surround nets for small pelagics and smaller pirogues using hook and line for high value species or using set gill nets.

Conflicts with industrial vessels were common, especially when the latter were fishing illegally at night in nearshore waters having switched off their AIS. Loss of set gill nets was common as a result. Chinese and Spanish vessels were often involved in such conflicts, but the recent change of legislation requiring vessels to fly the Senegalese flag when they were operating for two years in Senegalese waters blurred the boundaries between domestic and international vessels.

While the discussions were raging high in the country at large about the pros and cons of fishmeal production vs. cheap food for locals, there was no fishmeal factory in Yoff.

When it came to fish marketing, Seynabou Diouf told the participants that she was getting up at 6 o'clock in the morning to prepare breakfast and ready the kids. Around 8 o'clock she would go to the landing site to buy freshly landed fish. The challenge was to get sufficient loans from the family or market partners so that she could buy enough fish at a good price to see on in the market. Sometimes fish could be scarce in the morning and she might have to spend much per crate.

When it came to fish marketing, Seynabou Diouf told the participants that she was getting up at 6 o'clock in the morning to prepare breakfast and ready the kids. Around 8 o'clock she would go to the landing site to buy freshly landed fish. The challenge was to get sufficient loans from the family or market partners so that she could buy enough fish at a good price to see on in the market. Sometimes fish could be scarce in the morning and she might have to spend much per crate.

If more boats came in in the afternoon, a glut might lower prices, but if she and other women did not have enough cash left, the boat captain might prefer to run up two hours north to Cayar rather than fetch a low price or sell on credit.

She indicated that the lack of formal and affordable credit was a huge challenge for the women fish mongers as not even family members would nowadays sell landed fish against credit.

Despite some technical difficulties and the need to translate between multiple languages the exchange between the Academy in Yoff, Senegal, and the team in San Andrès, Colombia, was interesting and inspiring for both sides. Perhaps it becomes a starting point for more exchanges.