It's almost an epic battle. On the one hand Paolo Fanciulli in Talamone, better known as Paolo, the fisherman, on the one hand, and the trawlers of Porto di Santo Stefano near Orbetello in Italy's Tuscany region, with tacit consent of several local authorities, on the other. You're forgiven to think instinctively it's a battle between David and Goliath. In more than one way it is. Paolo is determined to save coastal ecosystems, deploys innovative means and ways and does not get scared into submission. The trawlers operating often illegally at night in the immediate proximity of the coast reserved for artisans seem to have all the advantages on their side.

It's almost an epic battle. On the one hand Paolo Fanciulli in Talamone, better known as Paolo, the fisherman, on the one hand, and the trawlers of Porto di Santo Stefano near Orbetello in Italy's Tuscany region, with tacit consent of several local authorities, on the other. You're forgiven to think instinctively it's a battle between David and Goliath. In more than one way it is. Paolo is determined to save coastal ecosystems, deploys innovative means and ways and does not get scared into submission. The trawlers operating often illegally at night in the immediate proximity of the coast reserved for artisans seem to have all the advantages on their side.

The untiring commitment of Paolo and, in this case, also the growing public support for the inspiring cause of nature protection for the benefit of the many, has made progress and a good chance of carrying the day. He says, the sea gives us food and recreation, we can not only extract and destroy mindlessly. We also need to give back to nature so it can continue providing for us.

We met Paolo first through tv documentaries and newspaper articles. His battle resonated with Mundus maris support to other artisanal fishers and for the implementation of the Guidelines for sustainable and prosperous small-scale fisheries adopted by the FAO Committee of Fisheries in 2014. During our 2021 general assembly we pledged financial support to his initiative Casa dei Pesci (the House of the Fish) and paid a visit in early August to explore further collaboration.

But let's start in the beginning, the mid 1980s. Paolo was a young man then. As a boy, he had loved explore shipwrecks with the fauna and flora finding refuge in and around them. Later, stepping in the footsteps of his father he became an artisanal fisher. But contrary to some protection of the coastal strip on land thanks to the Uccelina Parc (Parco Maremma), the coastal sea was in very poor state. There was hardly any fish to sustain him and the family. He realised that the destructive bottom trawling happening clandestinely almost every night within the 3 miles reserved for small-scale fishers using passive and selective gear like himself needed to stop. Bottom trawling drags a heavy, often chained, net with metal reinforced boards across the ocean floor flattening anything in its way. It thus not only takes fish and shrimp, but also pulls up non-edible marine invertebrates and vegetation, such as valuable posidonia. Such trawling erases all smaller structures that are essential habitats for many species, including juveniles of valuable fish, an entire ecosystem. Paolo compares this type of 'fishing' with burning the forest to catch a wild boar. Not to mention the abysmal CO2 emissions from this type of fishing. Recent assessments of the CO2 emissions of the global fishing fleets, particularly those using actively dragged gear or engaged in distant water fishing, are much higher than previously assumed despite catches going down since the mid 1990s.

But let's start in the beginning, the mid 1980s. Paolo was a young man then. As a boy, he had loved explore shipwrecks with the fauna and flora finding refuge in and around them. Later, stepping in the footsteps of his father he became an artisanal fisher. But contrary to some protection of the coastal strip on land thanks to the Uccelina Parc (Parco Maremma), the coastal sea was in very poor state. There was hardly any fish to sustain him and the family. He realised that the destructive bottom trawling happening clandestinely almost every night within the 3 miles reserved for small-scale fishers using passive and selective gear like himself needed to stop. Bottom trawling drags a heavy, often chained, net with metal reinforced boards across the ocean floor flattening anything in its way. It thus not only takes fish and shrimp, but also pulls up non-edible marine invertebrates and vegetation, such as valuable posidonia. Such trawling erases all smaller structures that are essential habitats for many species, including juveniles of valuable fish, an entire ecosystem. Paolo compares this type of 'fishing' with burning the forest to catch a wild boar. Not to mention the abysmal CO2 emissions from this type of fishing. Recent assessments of the CO2 emissions of the global fishing fleets, particularly those using actively dragged gear or engaged in distant water fishing, are much higher than previously assumed despite catches going down since the mid 1990s.

What to do? Paolo tried many things, first filing lots of complaints with the coast guard and other authorities only to find out that they considered him the trouble maker rather than the trawlers. Together with other small-scale fishers, he also challenged the trawlers directly in 1990 by trying to block their harbour Porto di Santo Stefano - only to find out that his opponents managed to put pressure on local fish market to refuse his products. So he needed to find other ways to resist. In those days, it was prohibited to carry tourists on fishing boats, while agrotourism was already an established way of complementing rural incomes. He managed to convince the relevant authorities in Rome to allow what he termed 'pescaturismo' (fishing tourism). This enabled him to take tourists on board to experience the life of a coastal fisher for a day, helping with hauling the gill nets set the night before and hear the stories about local nature and the struggles to defend it. In the evening he runs a restorant at his home where people can eat the freshly caught fish and taste the difference to industrial or cultured products.

What to do? Paolo tried many things, first filing lots of complaints with the coast guard and other authorities only to find out that they considered him the trouble maker rather than the trawlers. Together with other small-scale fishers, he also challenged the trawlers directly in 1990 by trying to block their harbour Porto di Santo Stefano - only to find out that his opponents managed to put pressure on local fish market to refuse his products. So he needed to find other ways to resist. In those days, it was prohibited to carry tourists on fishing boats, while agrotourism was already an established way of complementing rural incomes. He managed to convince the relevant authorities in Rome to allow what he termed 'pescaturismo' (fishing tourism). This enabled him to take tourists on board to experience the life of a coastal fisher for a day, helping with hauling the gill nets set the night before and hear the stories about local nature and the struggles to defend it. In the evening he runs a restorant at his home where people can eat the freshly caught fish and taste the difference to industrial or cultured products.

Over the years, he has hosted some 20,000 people on his fishing trips making many friends and gaining supporters for his struggle. Memories of his childhood love for shipwrecks became an inspiration to put down obstacles onto the seabed to prevent the trawling. In 2006 the legal conditions were created and thanks to a European project one hundred concrete blocks connected by steel ropes could be sunk into the sea along the coast. The concrete blocks were useful, but not sufficiently numerous and close to one another to be completely effective. Enters Ippolito Turco, who had participated in one of Paolo's fishing trips.

Together with other friends they decided to form an association and create an underwater museum with sculptures formed out of marble blocks, a more inspiring sight and arising, as it were 200 million years ago, from the sea. One hundred of these had been offered by the owner of the Michelangelo cave some 200 km away in Carrara, Franco Barattini, another acquaintance from Paolo's fishing trips. The Casa dei Pesci was born.

Renowned artists were attracted by the project of turning the marble blocks of 10 to 15 tons each into sculptures and thus have works of art protect and become one with nature by offering new habitat for plants and animals.

Among the first to contribute as volunteers to the project were such luminaries as Emily Young from the UK, who spends several months each year working near Carrara. She has created several Guardians of the sea. Two, the Weeping Guardian and the Young Guardian, were part of the first lot of sculptures lowered into the sea, while another Guardian remained on land.

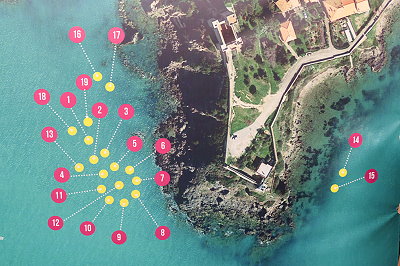

Other artists involved are Massimo Lippi (see above), Massimo Catalani, Marco Borgianni, Francesca Bonanni, John Cass, a student of Emily Young, and still others. So far, a total of 39 sculptures have been sunk, 19 in the immediate vicinity of Talamone as an easily accessible and inspiring underwater museum (see map on the right).

Other artists involved are Massimo Lippi (see above), Massimo Catalani, Marco Borgianni, Francesca Bonanni, John Cass, a student of Emily Young, and still others. So far, a total of 39 sculptures have been sunk, 19 in the immediate vicinity of Talamone as an easily accessible and inspiring underwater museum (see map on the right).

Paolo, the fisherman, and the Casa dei Pesci have become celebrities in the meantime and keen to raise additional funding to get more sculptures done and sunk into the sea to complete the mission.

A well-researched book by two renowned Italian journalists, Ilaria De Bernardis and Marco Santarelli, narrates the four decades of the struggle and tells the story in vivid terms and suggestive pictures. It was first published in May 2021 and is already in the second edition, expected to help the fund raising as well. A review is planned for this website.

The team of Casa dei Pesci is currently looking for publishing houses interested in English and German editions given the particular interest of German tourists in Paolo's fishing trips and their openness to environmental protection. Suggestions on anything helping the protection of the coastal and marine ecosystem in Tuscany can be made to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or by contacting Casa dei Pesci directly.

When visiting Paolo in Talamone as he was coming back from his daily fishing trip with tourists around lunch time, his cordiality and willingness to engage a conversation was contagious. Soon we chatted as if we had known each other for a long time and agreed the best would be to meet again. The burning sun reminded him that the fish on ice needed to be transferred to a fridge and cleaned and processed for dinner at his garden restaurant. There he keeps saying each evening that the sea gets saved at the table, when people learn to distinguish what high quality fresh from nature is. Later he will also warn that people need to use less soap and washing powder as he has observed increasing soap pollution in some coastal stretches as new threats.

Between lots of other tasks he explained that he needed to get a couple of hours sleep in the afternoon to be able to go out later at night with a small boat to set the nets for the following day. Then, early in the morning he would leave again with the next batch of his tourist guests lift up the nets and start all over again. Paolo is now sixty years old and starting to feel the strain. It's a passionate life, but certainly not an easy one.

Between courses at dinner, we were able to continue exchanging and plotting a bit more about possibilities for collaboration and entertain the 50 or so guests with stories about the challenges and opportunities of artisanal fishing in Italy, Senegal and elsewhere.

Between courses at dinner, we were able to continue exchanging and plotting a bit more about possibilities for collaboration and entertain the 50 or so guests with stories about the challenges and opportunities of artisanal fishing in Italy, Senegal and elsewhere.

Paolo is cooperating with research teams from Livorno and Siena on keeping turtles and dolphins away from the nets so that they do not get accidentally caught and drown. The good thing is that thanks to the protection already in place and reduced trawling some of the fauna is bouncing back. The fish have become more abundant. That attracts the dolphins, which are playful and loved by the tourists, but as marine mammals eat lots of fish. Paolo is happy to see them back and says there should be enough for the dolphins and for the fishers, provided they continue to use large enough mesh sizes to catch only adult fish and the underwater structures continue to develop and diversify protected habitats to increase the numbers and biomass.

The nets are equipped with pings that make sounds the dolphins don't like and thus stay away, continuing with the clicking chatter among the members of the pod. To keep out the turtles, however, pings don't work but light signals do. It's more work, but a necessary measure to protect the endangered species.

Imagine what could be achieved with more such initiatives turning the Mediterranean from an impoverished sea where 85% of fish populations are in bad shape into a healthy sea teaming with marine life again and producing good, affordable fish for riparian populations and the millions of tourists visiting each year. Join the effort and be rewarded with the revival of the sealife in Tuscany and a sense of mission accomplished - great satisfaction!

Text by Cornelia E Nauen, photos by Paolo Bottoni.