How to connect the big themes of sustainable development to local action while being mindful of the expectations of the local populations? This is the challenge we grapple with and are narrating here. The big themes are Sustainable Development Goal 14 "Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development" and the implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines for Ensuring Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines).

How to connect the big themes of sustainable development to local action while being mindful of the expectations of the local populations? This is the challenge we grapple with and are narrating here. The big themes are Sustainable Development Goal 14 "Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development" and the implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines for Ensuring Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines).

And the local action consists of bundling several strings of on-going activities into a coherent and dynamic whole, using Senegal as a test bed. What do we mean by that and what is the Small-scale fisheries Academy?

Mundus maris has conducted a number of activities over the years with and in coastal fishing communities. We wanted to conduct research and educational activities in a participatory mode, doing, what you may call 'critically engaged' science. As part of our basic mandate, we also lower access barriers and make validated scientific knowledge available to those otherwise excluded. It's part of our commitment to contribute to ocean protection, to fostering ocean cultures and the people of the sea. We pay particular attention to creating opportunities for young people. So far so good. So what have we done and learnt? And how is this helping with the implementation of the SSF Guidelines and making progress on SDG 14?

We started out with listening to fishers, women fish processors and vendors, fish mongers, traditional leaders and griots in Senegalese fishing villages in order to document how they live and what makes them tick.

Then, in 2011, we began developing some teaching aids for schools in coastal villages about the ecosystem approach to fisheries . We conducted these pilot activities for FAO's Nansen Project, in collaboration with teachers and school directors in Senegal and The Gambia to find forms of expression that sit well with cultural habits and meet teaching needs.

Then, in 2011, we began developing some teaching aids for schools in coastal villages about the ecosystem approach to fisheries . We conducted these pilot activities for FAO's Nansen Project, in collaboration with teachers and school directors in Senegal and The Gambia to find forms of expression that sit well with cultural habits and meet teaching needs.

A cultural day, organised by Mundus maris in 2013 under the theme "Battle for the Sea" in the prestigious Douta Seck Culture Centre in Dakar, was one of the highlights on this journey of joint exploration. The programme pulled together the science, the arts, the voice of community leaders, fish mongers and a theatre play of school children pleading for healing the badly polluted Bay of Hann, "Our sick neighbour".

Towards the end of the pilot activities with FAO, we also convened a capitalisation workshop with the directors and teachers involved, school inspectors and students to draw some lessons and cast our eyes forward towards what would be desirable follow-up activities according to the participants.

Meanwhile, we continued to engage with fish mongers. We used the fish rulers with minimum sizes of major landed species, developed as part of the teaching aids, to raise awareness about catches of undersized specimens in some fisheries and explore their willingness and capacity to change for more sustainable practices.

FAO further added attractive illustrations to the written teaching aids and printed a limited edition of guides for teachers and workbooks for pupils in English and French. When the Mundus maris Club Senegal started disseminating the materials in the schools, they figured that the teaching aids were also popular with leaders of fishers and that there was quite some demand for learning more about ecosystems and other research results.

FAO further added attractive illustrations to the written teaching aids and printed a limited edition of guides for teachers and workbooks for pupils in English and French. When the Mundus maris Club Senegal started disseminating the materials in the schools, they figured that the teaching aids were also popular with leaders of fishers and that there was quite some demand for learning more about ecosystems and other research results.

Annual celebrations of World Oceans Day, 8 June, were other opportunities to address ocean protection in conjunction with cultural and sports activities in small-scale fishing communities. The youth mobilisation also cast a light on the dark chapter of school drop outs, which reduced the chances of young people to take up work outside the already strained fisheries sector. Kids without an official birth certificate found it difficult to be admitted exams or even generally to school. This in turn triggered a successful campaign to obtain ordinary civil status for those affected.

Taking stock in a public conference in September 2016 organised by the Mundus maris Club Senegal, the birth certificates obtained for 245 children did not only impact the individual kids, but instilled a sense of hope and determination, that it was possible to change for the better.

All the while, our continued efforts also led to some video-interviews in order to use a diversity of means to give a voice to community leaders from small-scale fishing communities. And our focus on working with small-scale fishers, not primarily about them or the fish they catch, induced some action research in 2014-2015 the ripple effects are still unfolding.

On the one hand, it triggered additional interest through academic and other presentations and publications, thus contributing to demarginalisation of small-scale fisheries in line with the SSF Guidelines. On the other hand, it helped fishers, fish mongers and women in fisheries to articulate better their criticism and aspirations in terms of research questions and playing a recognised role in knowledge production and sector management. And this is precisely, when the idea of an Academy for and with small-scale fishers started to take shape.

On the one hand, it triggered additional interest through academic and other presentations and publications, thus contributing to demarginalisation of small-scale fisheries in line with the SSF Guidelines. On the other hand, it helped fishers, fish mongers and women in fisheries to articulate better their criticism and aspirations in terms of research questions and playing a recognised role in knowledge production and sector management. And this is precisely, when the idea of an Academy for and with small-scale fishers started to take shape.

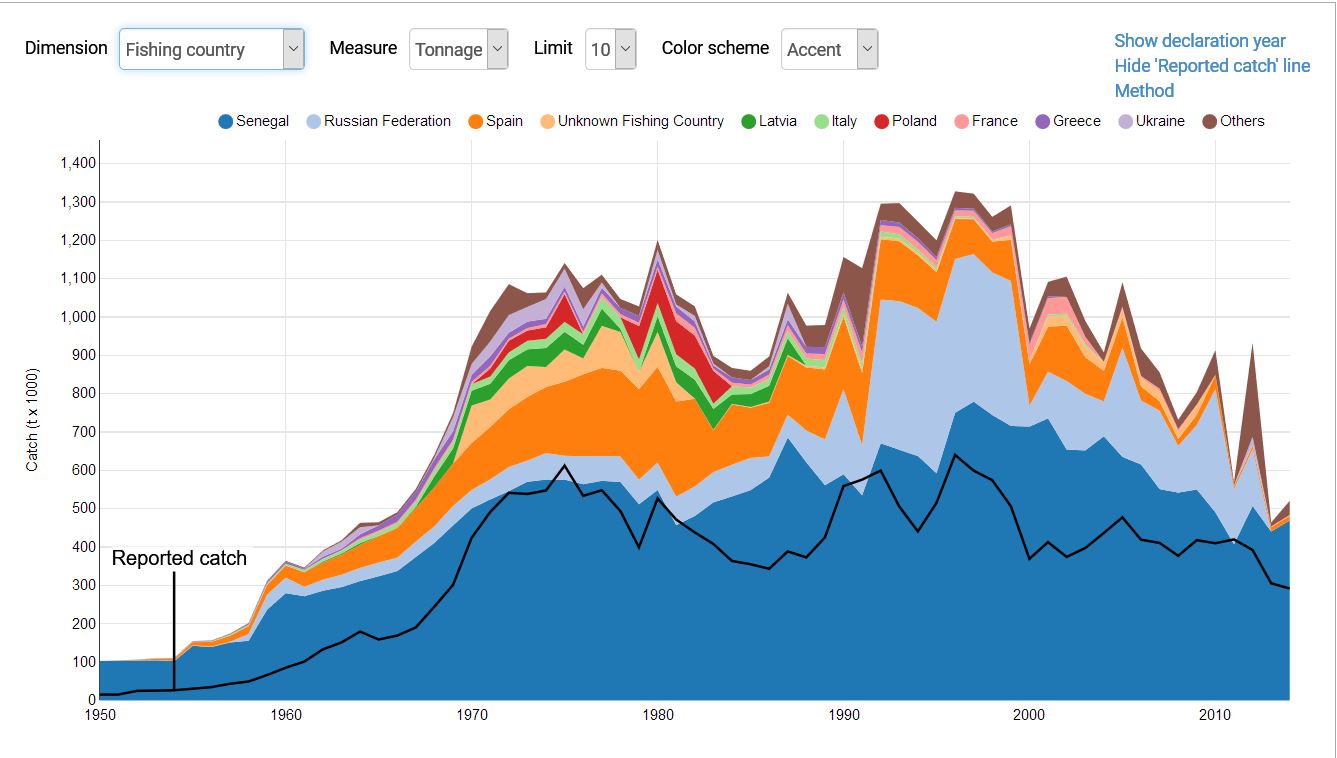

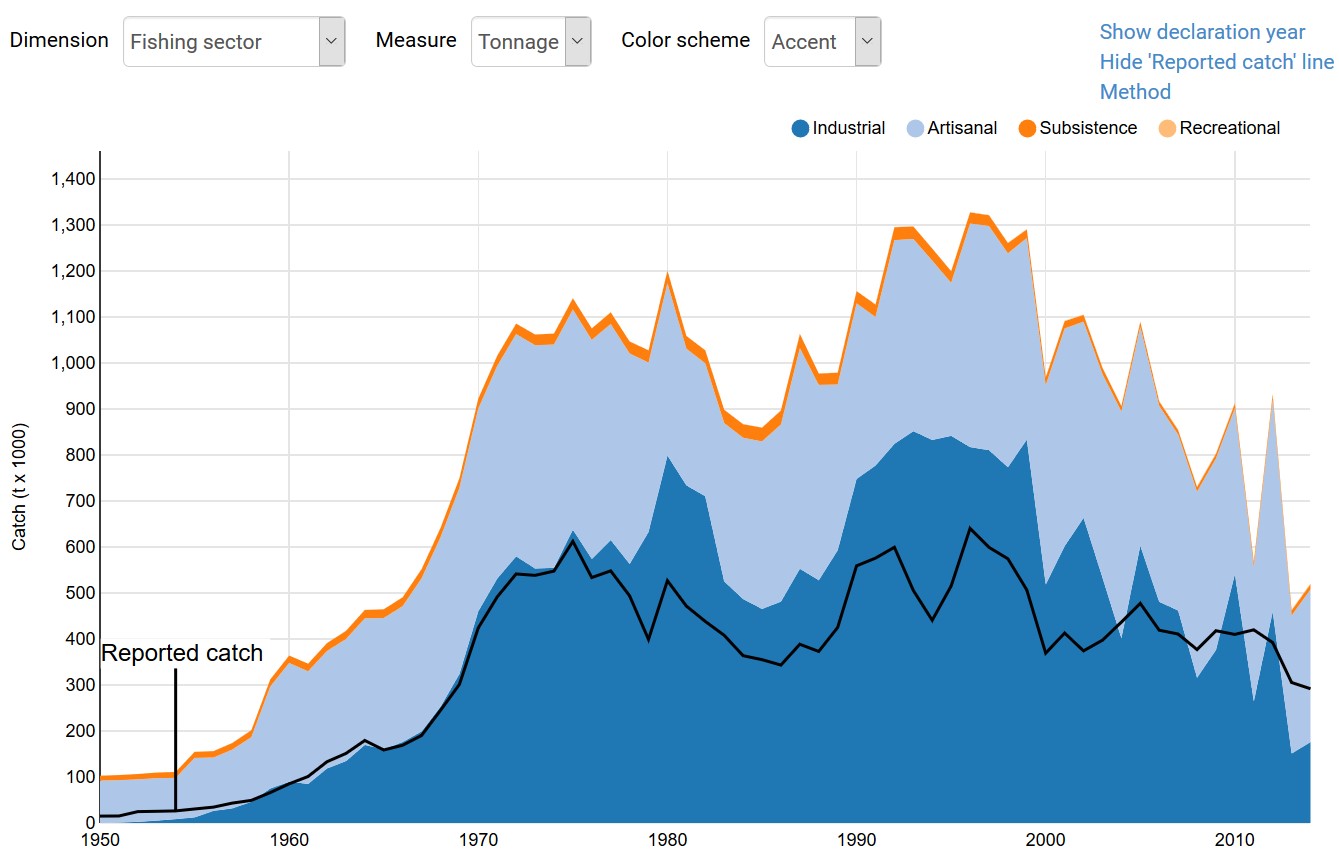

The immense achievement of the Sea Around Us Project reconstructing real catches (compared to those officially communicated to FAO by often underresourced government statistical services) is a great encouragement. The project provides the foremost global contribution for distinguishing between industrial, commercial small-scale, subsistence and recreational fisheries and separating legal and illegal catches (including estimates for discards at sea). It thus allows a good starting point for quantifying the role of small-scale fisheries in food security and fish food supply and marketing.

Recognising small-scale fisheries and the fishers for how important they are and working with them in new ways is the central concern underpinning the idea of the SSF Academy as a space for dialogue and exchange, for collective learning and action.

The demand for empowerment pervading the SSF Guidelines and the people-centred aspects of SDG 14 needs such a space and the mutual learning processes to come to life. We believe that the Grand Challenge of transiting our societies to sustainable ways of consumption and living with the ocean need to be connected to the local ground realities of small-scale fishers, their production, culture and relationship to the sea. For such transitions to happen it needs experimentation and trials at scales that do not threaten people's livelihoods and existence, but rather mobilise and hone the best innovative capacities.

The demand for empowerment pervading the SSF Guidelines and the people-centred aspects of SDG 14 needs such a space and the mutual learning processes to come to life. We believe that the Grand Challenge of transiting our societies to sustainable ways of consumption and living with the ocean need to be connected to the local ground realities of small-scale fishers, their production, culture and relationship to the sea. For such transitions to happen it needs experimentation and trials at scales that do not threaten people's livelihoods and existence, but rather mobilise and hone the best innovative capacities.

Here we post an initial draft outline of an SSF Academy as a test case in Senegal, but with sufficient generic elements to be of interest to other countries as well. We hope to stimulate debate and collaboration (including co-funding) for developing the concept and its exemplary implementation through a learning by doing approach. We expect that this will allow to sharpen the working hypotheses and generate opportunities to test alternative approaches to currently often unsatisfactory management modes. We hope that other teams are willing to join on this exploratory journey and support the learning process through critical participation, accompanying research and further dissemination. These experiences should rather mobilize the populations concerned and help to perfect their practices where they are at their best while stimulating their capacities of innovation.

To get a sense of the importance of the different types of fisheries, we refer to the public Sea Around Us catch reconstruction database. Reconstructed catches in 2014, the latest available year at the moment, artisanal (commercial) catches were estimaded at 331.760 tons, industrial catches at 176.150 tons, subsistence catches at 11.520 tons and recreational catches at 1.430 tons.

Note that the black line are officially reported catches, now in times of declining catches accounting for a larger share of the total compared to earlier decades.

The more than 60 years of catch reconstructions by fleet and fishing country illustrate clearly the importance of artisanal fishing and value chains in the country and why supporting their sustainable operation warrants an academy as a secure place for co-learning and co-production of knowledge for wellbeing in the sector, protection of marine biodiversity and better governance.

Cornelia E Nauen & Aliou Sall